Today, planning a days-long event for an expected 50,000 people would likely involve meticulous medical oversight and strict attendance caps. Fifty years ago, when more than eight times as many people than predicted showed up for Woodstock, organizers pulled off the event without either.

The result was a whole lot of cut-up feet, at least two births and two deaths — the cause of one of which has long remained murky.

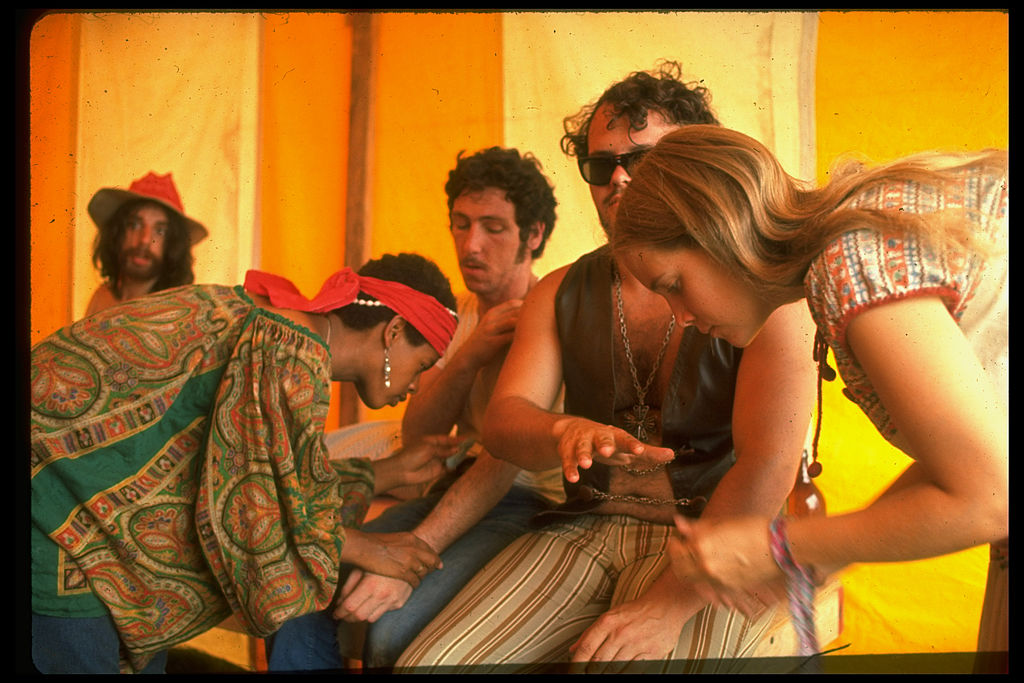

From Aug. 15 to Aug. 18, 1969, between the chords of Jimi Hendrix’s rendition of “The Star-Spangled Banner” and Richie Haven’s “Freedom,” crowds at Woodstock roamed the venue at Max Yasgur’s 600-acre farm in Bethel, N.Y., hanging out, dancing and smoking. Behind the scenes, organizers scrambled to keep up. Providing proper food, water and sanitation became a major concern as attendees camped out in what Ethel Romm, reporting on the event for the Middleton Times Herald Record, called “ghetto conditions” in a “temporary tent city of 450,000.”

Dr. William Abruzzi, dubbed the “Rock Doc,” was initially hired to oversee medical issues but quickly recognized that he would need some backup. Organizers began to fly doctors and nurses in from neighboring cities and towns. Local hospitals were put on alert. Some Woodstock attendees with medical expertise even lent a hand. One of their concerns had to do with drugs. The Hog Farm, a commune in Santa Fe, N.M., brought its members to help therapeutically treat concertgoers who experienced bad trips. According to Abruzzi’s original medical record of the event, provided to TIME by the Museum at Bethel Woods, 742 overdoses were reported throughout the three days, 28 of which required medication.

And yet, despite precautions, two deaths occurred during this historic musical event.

In one distressing case, a 17-year-old boy from Newark, N.J. named Raymond Mizsak was run over by a tractor while asleep in his sleeping bag. According to the original police report, which TIME obtained from the Museum at Bethel Woods, authorities responded to the scene around 9:00 a.m. on Saturday, Aug. 16, the second day of the festival. The report contains a statement from one of the drivers, age 29, which reads, in part: “We went over this route twice to clear the passage of people and garbage before, trying to get through. The first we noticed anything was when a person yelled at us. I saw the victim and yelled to get a doctor and ambulance.” One bystander reportedly tried to stop the tractor but could not get the driver’s attention until it was too late.

The other person to die was an 18-year-old Marine bound for Vietnam named Richard Bieler. His death is a more complicated story, and much less widely reported on than that of Mizsak.

Coverage of Woodstock often attributes the festival’s second death to a drug overdose. But in his book Woodstock ‘69: Three Days of Peace, Music and Medical Care, author Myron Gittell touches on the idea that Bieler’s death may not have been an overdose, but rather the result of hyperthermia and an inflammation of the heart muscle, possible side effects of Thorazine that was administered to combat an overdose.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

Still, the vast majority of Woodstock attendees got through the three days unharmed.

Despite reports of widespread drug use, the most frequent injury at the festival was a cut foot, according to Abruzzi’s medical report. In total, 836 foot lacerations were treated by Abruzzi and his team, as more and more festivalgoers opted for bare feet rather than muddy, soaked shoes. However, this number varies between accounts, with the Journal of Emergency Medical Services (JEMS) reporting 938 cases. The medical staff worried about tetanus and pneumonia. In total, staff treated at least 3,000 total patients over three days, JEMS states.

Gittell attended the festival too, but not as medical personnel. He was selling snow cones to hungry festivalgoers; only later did Gittell study the event’s health-care history in depth. He didn’t experience any health issues himself or see anyone who did, and says most people did not have those concerns at the time. “What was crazy was it didn’t get crazy,” Gittell says.

Abruzzi too was shocked by the relatively small number of health crises, and said so in his official report: “This might very well have been an example of the first time that a large number of people have come together, lived together, suffered together, and given to the rest of us an indication that it can be done in love and peace.” (It’s hard to say how Woodstock’s injury list compares to those of more recent music festivals, thanks in part to security regulations like the mass-gathering laws that were enacted in New York in the years following Woodstock. In fact, stricter regulations contributed in part to the Woodstock 50 cancellation earlier this month.)

According to Abruzzi, there was not one single instance of interpersonal violence at the event.

And in fact, there were a few moments that particularly underlined the love-filled atmosphere of Woodstock. Many reliable accounts document that there were also at least two births during the three-day event: one woman gave birth in a traffic jam outside the festival grounds, and one woman went into labor at Yasgur’s farm and was airlifted to a local hospital to deliver. Abruzzi and the New York Times reported sparsely on these instances, and several other eyewitness accounts appear in Gittell’s book.

However, the Museum at Bethel Woods can confirm specific knowledge of just one of the festival births. In a recently shot video from the museum, Howard Welsh, who at the time was working as a radiologic technologist at nearby Monticello hospital, claims to have been on the medical-evacuation helicopter team that took a woman there to give birth.

Welsh tells TIME that he helped deliver a baby girl by the entrance of the hospital, after the mother started to deliver before they could get her into a room. “I was holding the head and the shoulders were out,” he says. “Afterward, I almost passed out.” He says he can still remember the sound of the baby’s cries.

But to this day, the alleged Woodstock Babies have never been identified, and the details and medical records of the individuals are protected by law. While their identities remain a mystery, their births mark a much-imagined Woodstock moment.

“There have been novels written,” Gittell says of the mythical flower child. “I went to a play about the Woodstock baby.” On Woodstock’s 40th anniversary, The Associated Press sent out a call with an article that read, “Welcome to middle age, Woodstock Baby, if you’re really out there.” Now, as those children turn 50, the search continues.

However, Welsh, who went on to become director of medical imaging at a hospital in upstate New York, claims he met the Woodstock baby—and not just when she was born. He says that some time in the mid- to late 1990s, a woman walked in to get an MRI. After chatting with one another about Woodstock and her personal connection to the festival, Welsh says he realized that this was the woman he had helped deliver back in 1969.

“I mean, how could that ever happen?” Welsh says. “The chances of that happening again are like one in 10 million.”

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision