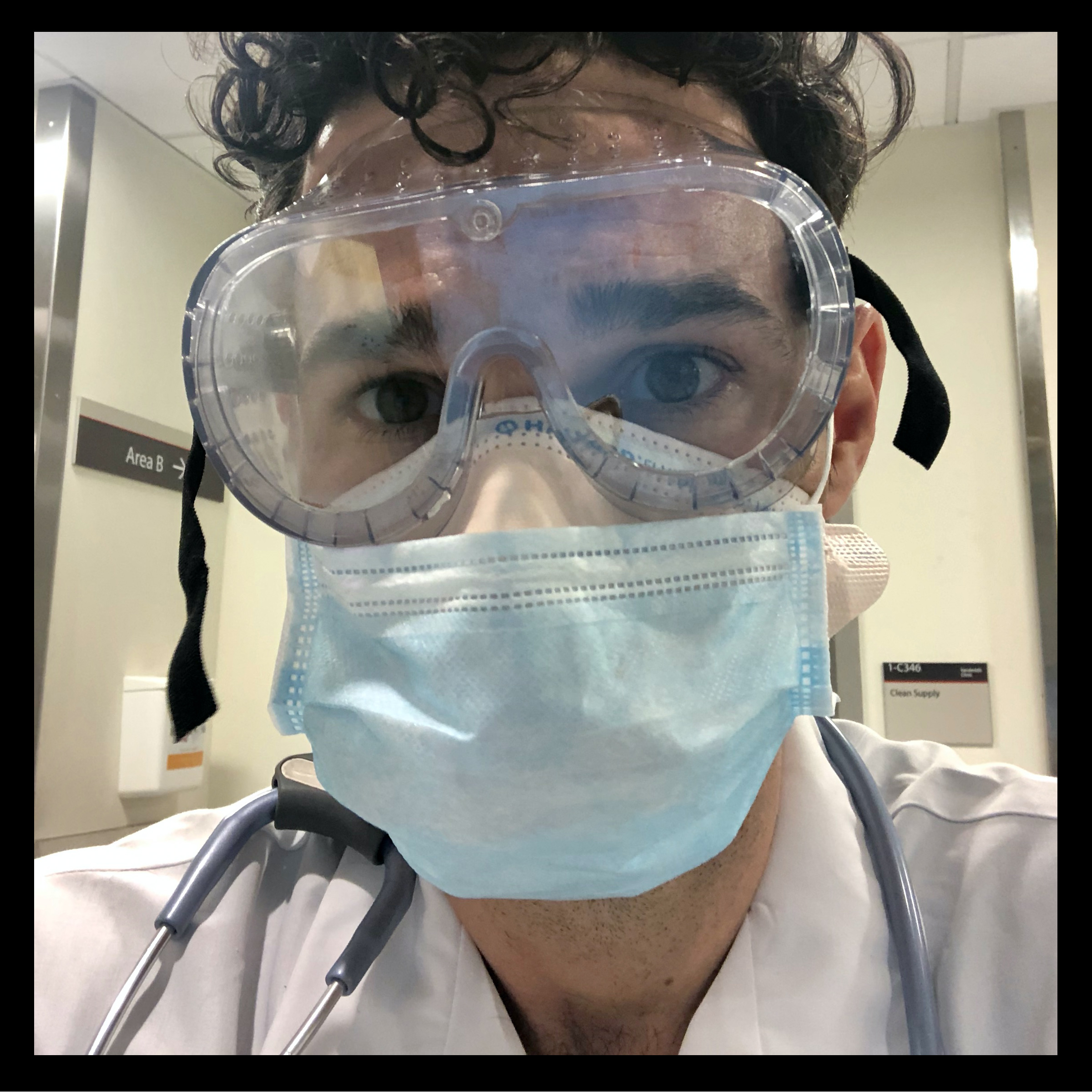

Dr. Craig Spencer, 38, is director of global health in emergency medicine at New York-Presbyterian/Columbia University Medical Center in New York City.

I survived Ebola in 2014. I fear COVID-19. When I walk into the emergency room, there’s a deep fluorescent light that beams off of everyone’s goggles. You can’t see their eyes. You hear alarms from the monitors and all different types of coughs—deep, frequent, harsh. It’s a horrible, sad symphony of coughs. Everyone is dressed in gowns. In the past, you’d see maybe one or two people wearing gowns to take care of a patient. Now, it’s every single patient that you have to be concerned about.

We have a lot of patients who are really sick, who are being intubated. Many of them are elderly or already ill and will likely never come off a ventilator. They may end up neurologically brain-dead, in a vegetative state. While our ER has always been full of sick people, we never thought we’d see anything of this magnitude here in the United States.

When my shift is done, there’s a moment when I switch off. I wash my hands and I use sanitizer. My wallet, my bag, my stethoscope—any of my belongings that come home with me—are immediately cleaned with a bleach wipe. Once I walk out of the hospital and I’m in the open air, I take my mask off and sanitize my hands again. When I get to my house, I remove my shoes and coat and put them into a bag outside. Then, I take off my pants and shirt at the front door. I have to separate from my child—my wife keeps her away. It sucks. She hasn’t seen me all day. She’s screaming, ‘Dada! Dada! Dada!’ It’s really jarring.

From personal experience, Ebola certainly is scarier. On average, it kills about half of the people it infects. You’re not likely going to get it unless you’re working in West Africa or taking care of patients, like I had been when I contracted it. We all knew what we were getting into. We all knew there was a risk. With coronavirus, this isn’t what many doctors signed up for. They’re physically and mentally exhausted.

On March 24, I decided to tweet about what it was like inside the ER because there’s a big disconnect between what I’m seeing and what people outside of what I’m doing were seeing on empty streets. I just needed to catalogue it so people know how intense this is—I thought it was really important. That was the only way we could let people know what the reality was.

There’s a huge likelihood that my colleagues and I will be infected. Some of them already have been and many have conceded they eventually will be. The question for all of us is, how long can we stay away from our families, from our friends, from our loved ones and from our children? It’s a sad, calculated risk that everyone is having to take. —As told to Melissa Chan

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy