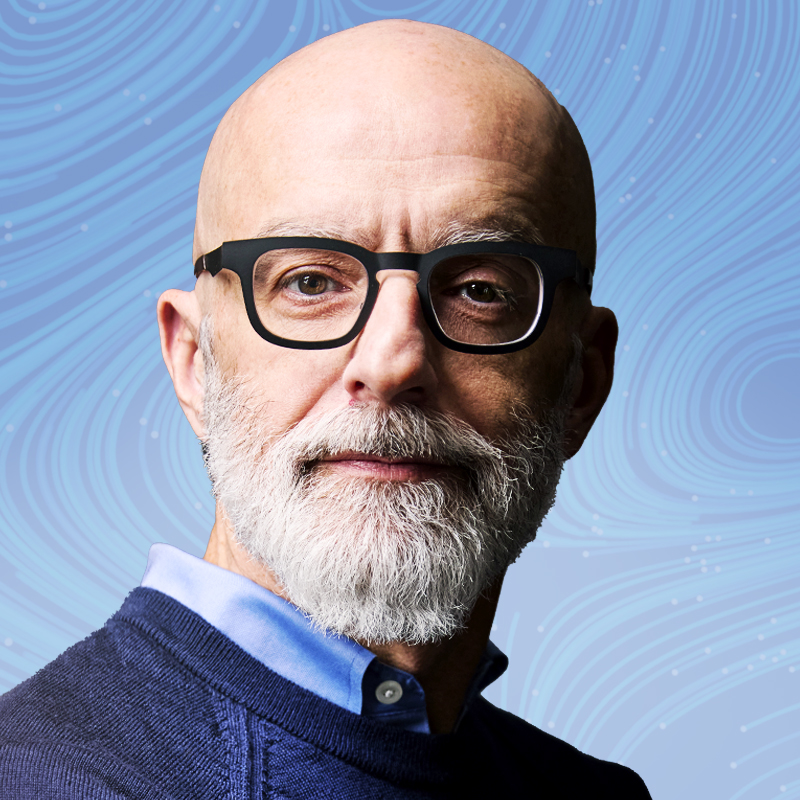

Sean Mayberry has had a lifelong front-row seat to depression. He grew up in a poor family in western Massachusetts with two parents who exhibited many symptoms of depression, though he didn't realize it at the time. “For me, that was normal to have parents with those symptoms,” he says.

Then he spent time working in Africa as a foreign-service officer, and realized that his African friends, neighbors, and colleagues were suffering from different levels of depression too. “It was frustrating because, being a privileged Westerner, if I had that issue, I could go to the embassy doctor and get help,” Mayberry says. But mental-health treatment was not so available to locals. In another role years later, he’d travel to different villages in the Democratic Republic of Congo, leading programs on HIV/AIDS and malaria prevention, family planning, and maternal-health issues. Inevitably, 20% to 30% of the population wouldn’t respond to the interventions—and Mayberry theorizes it’s because they may have been depressed.

In 2012, Mayberry read an article about research that suggested group interpersonal psychotherapy was an effective way to treat depression among people in rural Uganda. He was living in New York City at the time. “I literally jumped on the No. 2 train, shot up to Columbia, and banged on the door of one of the researchers,” he says. “I said, ‘Is this true?’” Then he quit his job to launch StrongMinds, which aims to treat depression in sub-Saharan Africa by training community members to lead group talk-therapy sessions over a six-week period. “My kids were small, and they were like, ‘What is dad doing up in the attic?’” he says, recalling his early days plotting the new venture. He yelled back: “I’m ending depression in Africa.”

Fast-forward more than a decade, and he’s on his way. As of February, StrongMinds has provided 500,000 Africans with treatment; the million mark is in sight next year. During sessions, participants learn how to identify the triggers of their depression and how to address them. Last year, the nonprofit’s cost per patient was just $39.

Six months after receiving treatment, 80% of attendees are depression-free. Many of the Africans who meet in group therapy form tight bonds, and turn to each other during tough times weeks and months after their treatment ends. “We’re democratizing depression,” Mayberry says. “If we don’t do this, no one will.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com