Last December, at a rally in New Hampshire, Donald Trump asked the crowd a surprising and revealing question: “Were you better off five years ago or are you better off today?”

It’s surprising because it deviated from what generations of presidential candidates trying to beat a first-term incumbent had asked at similar moments: Were you better off four years ago? That age-old question would be especially apt in this year’s election, since four years ago, Trump himself was in the White House, with the fate of the nation in his hands. Voters have good reason to consider how they felt about their own security and the state of the union during 2020, and to compare it with how they feel today.

It’s revealing, because it so powerfully illustrates Trump’s strategies for reclaiming the Oval Office: Encourage Americans to deny, ignore, or forget just how dangerous and dysfunctional life was here four years ago, and to repress our memories of his government’s chaotic, and policy response to that year’s crises. In the 2024 election, Trump has a great deal to gain from avoiding conversations about what happened during 2020. The rest of country, however, has everything to lose by treating the year as an anomaly, and acting as if what happened in the US does not count.

At first, Trump simply denied the risk. “We have it totally under control,” he told CNBC, on January 21. The next week, January 28, national security advisor Robert O’Brien told the president that, in fact, “This will be the biggest national security threat you face in your presidency.” When, in early February 25, 2020, Nancy Messonnier, the director of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases at the CDC, told the press that “we expect we will see community spread in the United States. It’s not a question of if this will happen, but when this will happen,” the president demanded she be fired.

Denial led to magical thinking and bizarre decisions that sewed division and distrust. Remember when, in March, the president refused to let a cruise ship with infected Americans return to shore because “I like the numbers where they are”? When the government declared that certain people were “essential workers,” but refused to guarantee them personal protective equipment, let alone extra compensation and better health care? When, in April, Trump announced that the CDC was now recommending that Americans wear masks in public, but immediately declared “I’m choosing not to do it”? Or when, in December 2020, he refused to get vaccinated on television or promote the vaccines that his own government had helped bring to market (and could reasonably claim as a policy breakthrough), because he didn’t want Joe Biden to get the credit?

There are reams of research showing how the American response to 2020 allowed the COVID-19 to run rampant, leading to more severe disease and excess death than was necessary, particularly for a nation that was, as global health experts saw it, so well prepared. What we’ve yet to assess is the way Trump’s pandemic leadership damaged our already-fraying social fabric, and made the social experience of 2020 so durably catastrophic that it remains with us today.

Read More: The Pandemic Sacrifices of 20-Somethings

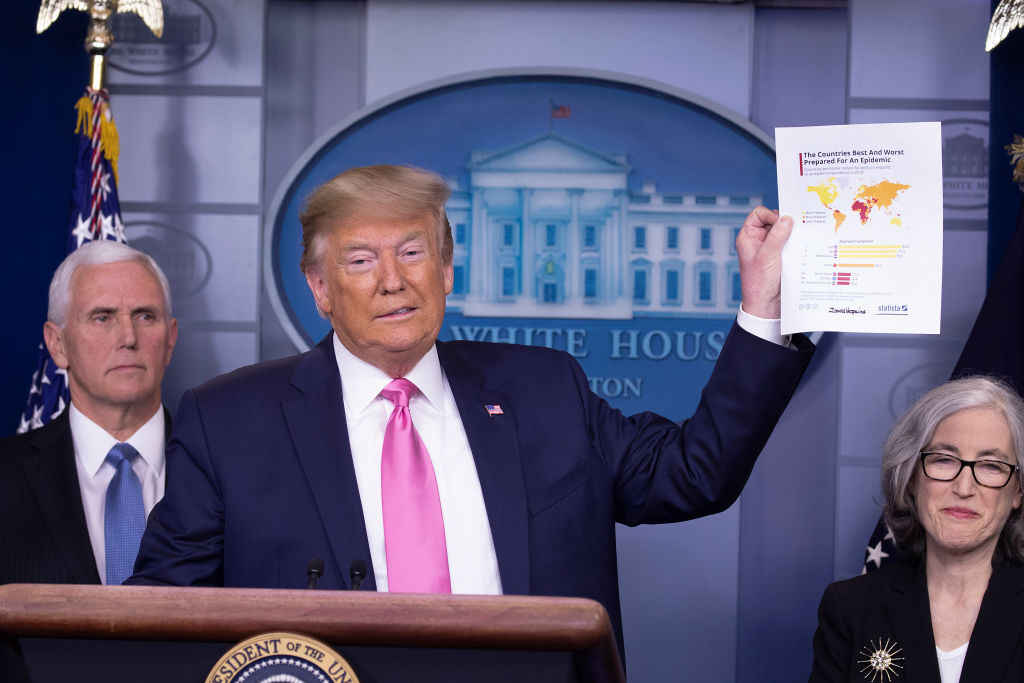

By nearly every measure, the U.S. response to the threats of 2020 made the situation worse than was necessary. Recall that, in 2019, the Global Health Security Index rated the US better prepared for a pandemic emergency than any other nation. In 2020, however, the federal government failed to execute its plan. Or any plan, really. But in the cacophony of competing ideas and conflicting instructions, we grew more socially distanced, ideologically divided, and distrustful of core institutions. At a moment when we needed solidarity, Americans experienced the opposite: alienation and anomie.

Consider the way we treated each other. A great many people remember 2020 as a time of surging crime rates. A record increase in homicides. Vandalism at Black Lives Matter protests. Domestic violence, alcohol and drug use, lethal overdoses, all at alarming levels. Gun sales soared, as did carjackings and hate crimes. Price gouging abounded. Reckless driving spiked. But COVID alone isn’t to blame. Despite what collective memory suggests, the truth is it took months before most of these numbers started climbing. So what changed?

When Americans returned to the public realm after the first wave of shutdowns in 2020, they were full of ire and indignation, with each side of the polarized electorate convinced that the other was responsible for the country’s miserable condition. By late spring, fights over masks had turned a few square inches of fabric into a battleground for the soul of the nation, and routine encounters in public spaces were suddenly shot through with rage and tension. The gas station. The grocery store. Streets and sidewalks. All became hot spots for confrontation. No place was safe.

Experts often attributed this spike in destructive behavior to the forced isolation of Covid-era social policies. But nearly every nation experienced changes in social life that were similar to what happened in the U.S. during 2020. In most of Europe and Asia, the lockdowns and distancing mandates were far more severe than they were in America; stress and anxiety were high as well. Yet no European or Asian society saw rates of destructive behavior rise at anywhere near the American level. In fact, the reverse happened: most of them witnessed a remarkable decline in violent crime.

Distrust - of government, science, and other citizens – was rising throughout the U.S. in the tumultuous years leading up to the pandemic. Since COVID hit, it has become the nation’s default condition. In 2024, when misinformation is everywhere, extreme views have an outsized influence on the media, and every side feels entitled to its own facts, achieving trust is an accomplishment. Without it, the American electorate appears ready to erupt.

Building trust is still possible, though, even in divided societies whose leaders are disdainful of established scientific truths. Australia, for instance, entered 2020 in a state of emergency, politically polarized and battling a different existential threat. In December, 2019, apocalyptic bushfires incinerated millions of acres and displaced thousands from their homes. Scott Morrison, the conservative prime minister, faced fierce criticism for refusing to acknowledge the role of climate change in the ecological catastrophe; his deputy minister called those who worried about global warming “raving inner-city lunatics.” But reports of the new coronavirus led Australians to close ranks and tone down the divisive rhetoric.

In February, 2020, Morrison warned of a crisis that “could last up to ten months” and cause significant social and economic hardship. Australia’s national government deployed army personnel to a mask factory, where they ramped up production, and enlisted 130 private companies to manufacture PPE. It invested in rapid COVID tests, quickly becoming a global leader in identifying and isolating positive cases, and made plans for tracing as well.

Australia’s most important early policy innovation was the creation of a National Cabinet for managing the disease outbreak, made up of the prime minister as well as the first ministers and chiefs from every state and territory. Members of the National Cabinet belonged to different political parties and governed territories with unique population profiles, living conditions, and levels of exposure to the disease. The goal was to set up a space for genuine collaboration, where leaders could assess new data and scientific research, information that would help the country balance national policy priorities with local preferences and needs.

There were, to be sure, points of disagreement and periodic protests about lockdowns and social restrictions. In time, journalists discovered that Morrison had used the crisis as occasion to seize unprecedented political power across federal agencies, and ultimately this overreach led to his fall from office. But while most nations struggled to contain lethal outbreaks, Australia registered roughly the same amount of mortality in 2020 that it does in typical years – had the U.S. held the death rate to the same level, roughly 900,000 lives would have been spared.

What’s more, the success they achieved, collectively, by complying with public health restrictions made Australians more trustful of their fellow citizens. In a survey conducted in August, 2020, 54 percent of Australians said the country was more united than it was before COVID; and Australians were more likely to believe that “most people can be trusted” as well. During 2020, most Australians were willing to look out for each other and respect public health orders, from mask mandates to distancing requirements and stay-at-home orders. Their pro–social behavior helped generate a virtuous circle, while Americans fell into a death loop.

Today, Americans’ trust in most institutions is at or near historic lows. Our distrust of science and scientists has grown even more rampant than it was in 2020, with a mere 57 precent of the population saying science has a ‘mostly positive effect on society,” compared to 73 percent in 2019. Trust in the federal government is also declining, with just one percent of Americans saying they trust the government in Washington to do what is right “just about always” and a mere fifteen percent agreeing that they trust it “most of the time.” Most alarming, perhaps, is that, since 2020, Americans’ trust in other people has remained at its historic nadir, with 45 percent saying they distrust “the American people as a whole when it comes to making judgments under our democratic system about the issues facing our country.” If – or when – the next crisis hits, this discord will put everyone in the U.S. at risk.

Perhaps the most important reason for Americans to think back to how things were four – and not five – years ago, is that crises, at this volatile moment, are to be expected. The next president will be responsible for managing the situation in Israel and Gaza, as well as threats of an expanding war in the Middle East or beyond. There’s Russia and Ukraine, China and Taiwan, North Korea, and Iran. There’s the ever-present threat of heat waves, hurricanes, and torrential rain events on a climate-changed planet. The markets are hotter than ever, and we haven’t seen the last new virus, either.

It may be comforting to believe that 2020 was a black swan, the kind of year we’re unlikely to see again in our lifetime. More likely, it was a canary in the coal mine, an early warning that we’ve entered the age of extremes. Our political leaders should be equipped for the challenge.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com