One recent morning, I texted a Democratic source to ask if she had time to talk about the presidential election. She replied: “I wish for death.”

She was kidding, obviously. But this doom and gloom is everywhere. You hear it at dinner parties and playdates, in casual conversations at the grocery store. The sentiment is always the same: “Are we seriously doing this again?”

The 2024 presidential election is a rematch between one man widely seen as too old for the job and another man widely seen as too dangerous. The prospect has left much of the country feeling both paralyzed and horrified. Call it the Dread Election.

A Yahoo survey last fall found that the most common feeling this election cycle—across age, gender, and party leaning—is “dread.” More than 4 in 10 American adults said they felt “dread” about the upcoming contest, more than the proportion that responded with words like “exhaustion,” “depression,” or “indifference.” Nearly half of women, white voters, and Democratic leaning voters say they dread the looming presidential rerun. Republicans have slightly less trepidation (their dread hovered in the mid-thirties) but they’re not in a great mood either. Strong majorities of both parties express dissatisfaction with their choices.

These feelings have settled like a fog over the contours of this race, making it difficult to see anything except skepticism about both candidates. But what’s clear is the surge of energy and mobilization that followed Donald Trump’s 2016 victory and buoyed Democrats through three subsequent national elections has not yet materialized in this one. Activists are exhausted. Volunteers are dragging their feet. Audiences are tuning out political news, with ratings down across major news networks. Grassroots political fundraising plummeted in 2023, forcing some Democratic organizations to tighten their budgets and lay off staff.

All this raises key questions for the Democrats. Can an incumbent win re-election without an engaged and mobilized base that is excited about their candidate? How important is enthusiasm, anyway?

Mood is a tricky thing to measure. I have spent the last eight years covering Democrats in the Trump era, chronicling the rise of young voters, the power of women organizers, and the activists trying to mobilize voters of color. I’ve spent the last eight months struggling to spot signs of that same energy being directed toward the general election that’s now upon us. At every turn, groups I expected to be mobilizing were not yet mobilizing. People I expected to be excited were decidedly not excited. Instead, nearly every conversation took on a tone of resignation that 2024 would be a grim sequel. Along the way, I realized that the persistent sense of disillusionment that greeted me at every turn wasn’t the obstacle to covering this race. It was its core theme.

Read More: Young Progressive Activists Lay Out Demands For Biden.

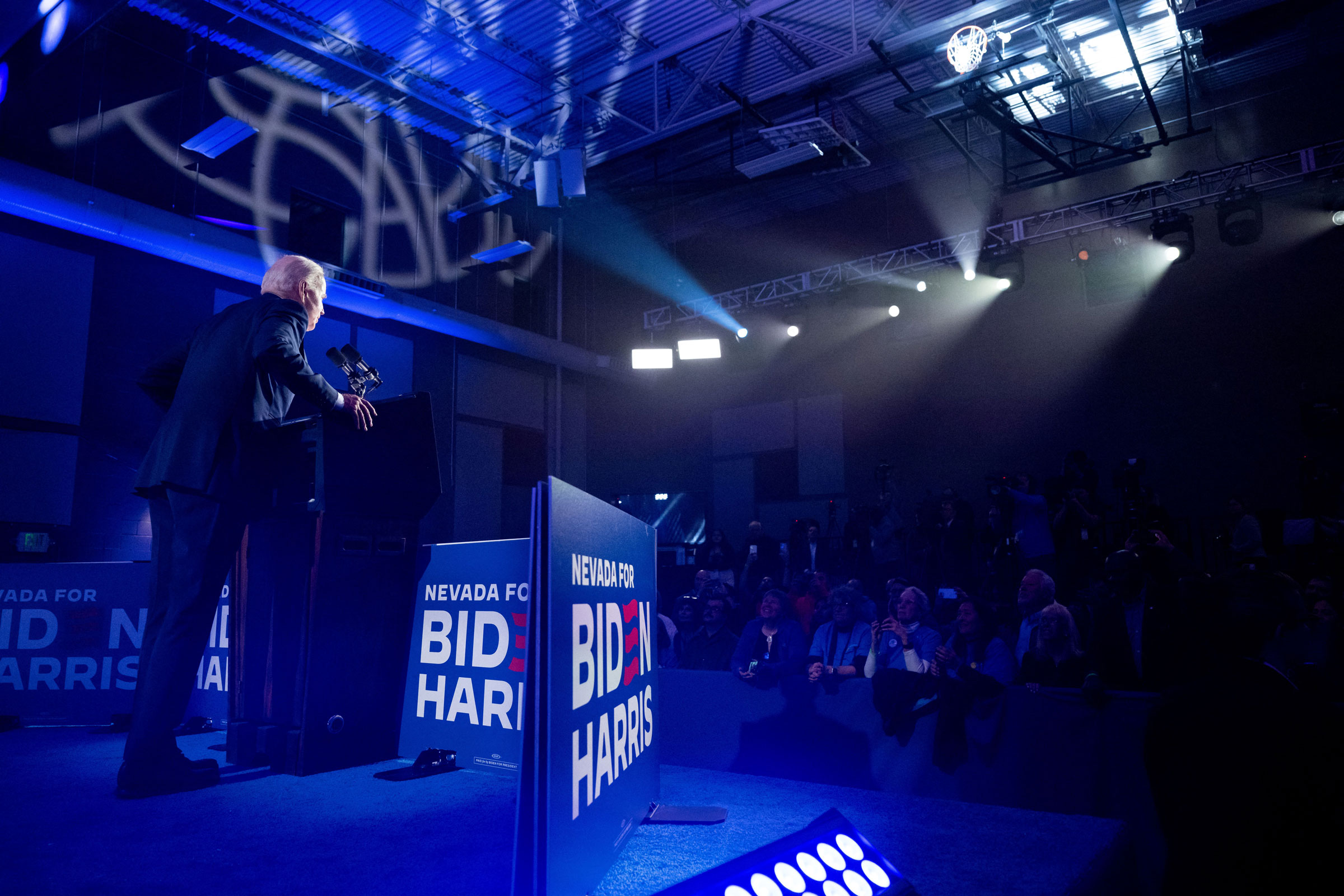

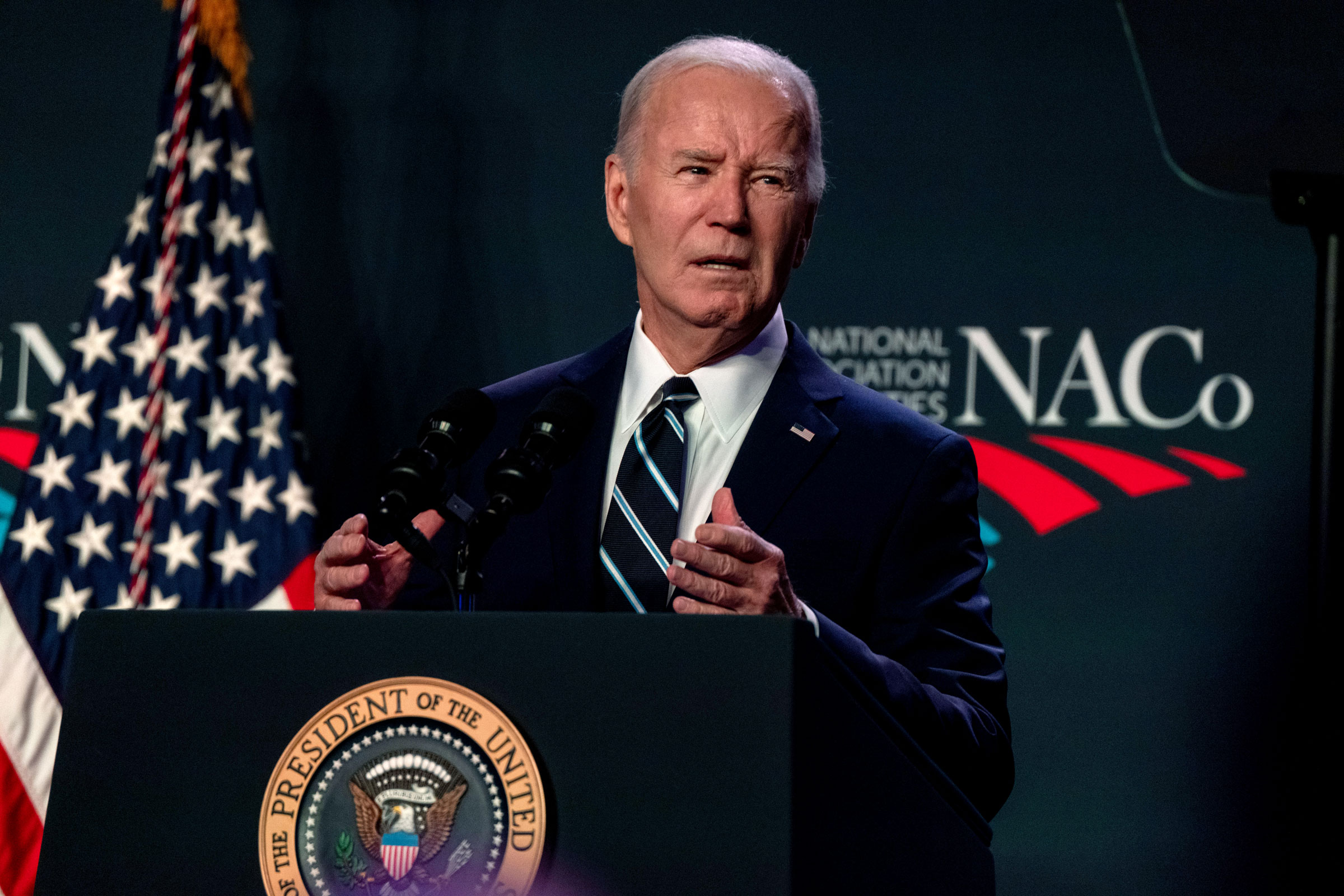

For Democrats, this lack of excitement has curdled into a darkening sense of despair as polls pile up showing Joe Biden losing to Trump—something that never happened in 2020, when all corners of the party were mobilized and turnout set records. Even then, Biden barely squeaked by. Now Trump is back for Round 2, and Biden is limping into the rematch with a fraying coalition, anemic polling, and a pervasive sense, even among many supporters, that he is not up to the job. In a recent New York TImes/Siena poll that found Trump leading by five points nationwide, just 23% of Democratic primary voters said they were excited about Biden—half the total of Republicans who said the same about Trump.

Which has left Democrats stuck in a “doom loop,” says Amanda Litman, co-founder of Run for Something, which recruits and supports millennial and Gen Z Democrats for office in races around the U.S. “I’ve spent the last year asking people to invest in work to save and sustain democracy. And I’ve heard, more often than not, ‘I’m tired. I’m tapped out.’”

Lori Goldman has spent the last eight years of her life working to defeat Trump. As the founder of Fems for Dems, a grassroots group of suburban Democrats in Michigan,she devotes nearly all her free time to building membership, hosting candidates, and organizing fundraisers. When she started the group, her triplets were 8. For nearly half their lives, Goldman’s political work consumed her—“seven days a week, seven nights a week,” she says. “I wasn’t there if my kids needed something.”

Now Goldman wonders: What was it all for? After all the weekend phone banks, all the school night fundraisers, the canvassing in rain and snow, after all the hours Goldman missed with her children, Trump heads into the general election seemingly stronger than ever, and vowing to pursue an even more aggressive second-term agenda. “I look at what I’ve sacrificed, what others have sacrificed. Is it worth it? No,” Goldman says. “It was a bad trade.”

“We’ve been in this dysfunctional marriage called American politics for all these years, and it doesn’t seem to be getting better,” she adds. She sometimes feels, she says, like an “emotionally abused woman.” Goldman senses she’s not the only one sick of the state of things. After Trump won in 2016, “We had new people coming constantly. I was stopped on the street by people asking: Fems for Dems, how could I get involved?” she says. “Now there’s no new people reaching out.” The wave of volunteers has slowed to a trickle.

Read More: First, They Marched. Now, They're Running For Office.

The dropoff in volunteer enthusiasm is part of a broader turn away from politics. Gone is the progressive obsession with politics that marked the early years of the so-called “Resistance era.” Many Americans are so demoralized that some Democratic activists fear they’ll simply tune out this election altogether. For much of 2023, there was a “politics on the back burner vibe,” says Leah Greenberg, co-founder of Indivisible, a national network of anti-Trump grassroots groups. The signs are everywhere. Traffic has plummeted on digital news sites. TV viewership of the GOP’s Iowa caucus, the only truly contested race of the primary season, was down 17% from 2016 levels, according to Semafor.

Meanwhile, the small donors that have funded much of the political infrastructure of the anti-Trump movement are tightening their wallets. Litman says Run for Something’s fundraising in 2023 fell short of their projections by 50%, forcing the organization to lay off staff. Emily’s List also had layoffs last fall—a striking development in the post-Dobbs era. “There’s less Resistance-era small-dollar donors,” says Maurice Mitchell, national director of the Working Families Party, “and less Resistance-era zeal.”

The Israel-Hamas war may have pushed Biden’s already tenuous coalition toward its breaking point. Young and more progressive voters were always skeptical of Biden; many showed up to vote for him in 2020 purely because he was the vessel to defeat Trump. Now, many of those reluctant supporters are making it clear that he can’t count on their vote this time around if he continues to align himself with Israel.

“Gaza is a daily conversation among rank-and-file voters in Georgia,” says Nsé Ufot, a prolific Georgia organizer who helped deliver the state to Biden in 2020 and win two Senate seats in 2021. “Saying ‘get in line’ doesn't work on the Democratic side, not in the way it works on the Republican side.”

Even for Democrats fully committed to supporting Biden, the war has made generating enthusiasm for Biden difficult. “In the online environment, there’s no space to talk positively about Joe Biden. It reminds me a lot of 2016 in that sense,” says Litman, who ran email organizing for Hillary Clinton in that race. “You couldn’t talk positively about Hillary without being harangued online. The same is true now for Joe Biden.”

The only thing that cures dread is hope. And there are real reasons for despondent Democrats to be hopeful, even as Trump rampages through the Republican primaries and tops Biden in early battleground polls.

Many Democratic strategists believe that voters’ energy and attention will be revived as the threat of a second Trump term comes into focus. Many may not wake up to the reality of a Biden-Trump redux until the summer conventions, campaign officials believe.

When that happens, they say, Biden’s base will overcome their reluctance and cast another vote for the incumbent—if only to block Trump. The former President remains the single most effective political organizer for Democrats, a reliable driver of blue voters to the polls. Democrats have beaten expectations in nearly every election of the Trump era, including low-turnout special elections and abortion referenda in red states.

Read More: How the Anti-Trump Resistance Is Organizing Its Outrage.

Democrats have other advantages in November. Biden is outraising Trump. The Republican’s legal problems haven’t gone away; despite his resounding primary victories, a significant proportion of GOP primary voters have expressed reluctance to vote for a candidate convicted of a felony. (Trump has been charged with 91.) Abortion remains a motivating factor for many voters. And organizers say that they fully expect some of Biden’s most grumbling critics to come out and vote for him anyway.

“Black voters were never super into Biden,” says Ufot. “The narrative is that he’s slipping, the vibe is that everything is terrible. But those things are not indicators of electoral behavior.”

Biden was never the candidate of enthusiasm. His role has never been to stir the masses. It’s been to defeat Trump and, in his supporters eyes, save democracy in the process. “Obama was a movement president; Joe Biden isn’t a movement president,” says Mitchell of the Working Families Party. “Joe Biden’s 2020 campaign didn’t ride on movement enthusiasm. It ultimately rode on making a clear argument about the stakes of this election.”

Those stakes are as high today as ever. And Greenberg says that the grassroots leaders who powered Democratic victories over the last three elections are now more seasoned and effective than they were in the early days. As Lori Goldman puts it: “We’re tired. But not too tired that we’re going to let Trump skate into that office.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Write to Charlotte Alter at charlotte.alter@time.com