As an academic who has spent the past 25 years developing techniques to detect photo manipulation, I am used to getting panicked calls from reporters trying to authenticate a breaking story.

This time, the calls, emails, and texts started rolling in on Sunday evening. Catherine, Princess of Wales, has not been seen publicly since Christmas Day. The abdominal surgery she underwent in January led to widespread speculation as to her whereabouts and wellbeing.

Sunday was Mother’s Day in the U.K., and Kensington Palace had released an official photo of her and her three children. The image had been distributed by the Associated Press, Reuters, AFP, and other media outlets. The picture then quickly went viral on social media platforms with tens of millions of views, shares, and comments.

But just hours later, the AP issued a rare “photo kill,” asking its customers to delete the image from their systems and archives because “on closer inspection it appears the source has manipulated the image.”

The primary concern appeared to be over Princess Charlotte’s left sleeve, which showed clear signs of digital manipulation. What was unclear at the time was whether this obvious artifact was a sign of more significant photo editing, or an isolated example of minor photo editing.

In an effort to find out, I started by analyzing the image with a forensic software designed to distinguish photographic images from fully AI-generated images. This analysis confidently classified the image as not AI-generated.

I then performed a few more traditional forensic tests including analyzing the lighting and sensor noise pattern. None of these tests revealed evidence of more significant manipulation.

After all this, I concluded it was most likely that the photo was edited using Photoshop or a camera’s onboard editing tools. While I can’t be 100% certain of it, this explanation is consistent with Princess Kate’s subsequent apology, issued Monday, where she said “Like many amateur photographers, I do occasionally experiment with editing. I wanted to express my apologies for any confusion the family photograph we shared yesterday caused.”

Read More: The Kate Middleton Photo Controversy Shows the Royal PR Team Is Out of Its Depth

In a rational world, this would be the end of the story. But the world—and social media in particular—is nothing if not irrational. I am already receiving dozens of emails with “evidence” of more nefarious photo manipulation and AI-generation which are then being used to speculate wildly about Princess Kate’s health. And while the type of post-hoc forensic analyses that I perform can help photo editors and journalists sort out stories like this, they cannot necessarily help combat rumors and conspiracies that quickly spread online.

Manipulated images are nothing new, even from official sources. The Associated Press, for example, suspended the agency’s distribution of official imagery from the Pentagon for a time in 2008 after it released a digitally manipulated photo of the U.S. military’s first female four-star general. The photo of Gen. Ann E. Dunwoody was the second Army-provided photo the AP had flagged in the previous two months. The AP finally resumed their use of these official photos after assurances from the Pentagon that military branches would be reminded of a Defense Department instruction that prohibits making changes to images if doing so misrepresents the facts or the circumstances of an event.

The problem, of course, is that modern technologies make the alteration of images and video easy. And while often done for creative purposes, alteration can be problematic when it comes to images of real events, undermining trust in journalism.

Detection software can be useful on an ad-hoc basis, highlighting problematic areas of an image, or whether an image may have been AI-generated. But it has limitations, being neither scalable nor consistently accurate—and bad actors will always be one step ahead of the latest detection software.

Read More: How to Spot an AI-Generated Image Like the ‘Balenciaga Pope’

So, what to do?

The answer likely lies in digital provenance—understanding the origins of digital files, be they images, video, audio, or anything else. Provenance covers not only how the files were created, but also whether, and how, they were manipulated during their journey from creation to publication.

The Content Authenticity Initiative (CAI) was founded in late 2019 by Adobe, which makes Photoshop and other powerful editing software. It is now a community of more than 2,500 leading media and technology companies, working to implement an open technical standard around provenance.

That open standard was developed by the Coalition for Content Provenance and Authenticity (C2PA), an organization formed by Adobe, Microsoft, the BBC, and others within the Linux Foundation. It’s focused on building ecosystems that accelerate open technology development and commercial adoption. The C2PA standard quickly emerged as “best in class” in the digital provenance space.

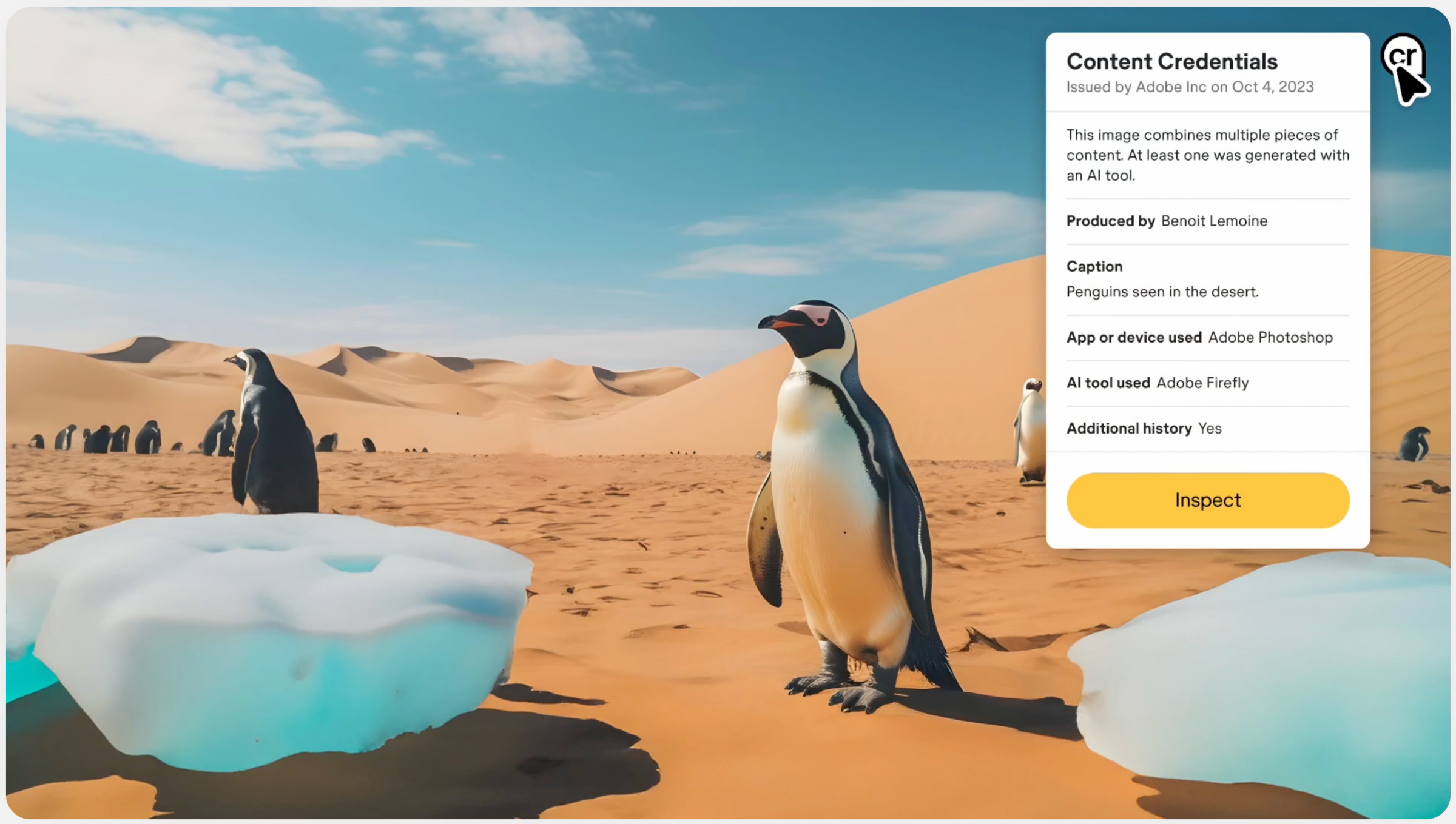

C2PA developed Content Credentials—the equivalent of a “nutrition label” for digital creations. By clicking on the distinctive “cr” logo that’s either on or adjacent to an image, a viewer can see where the image (or other file) comes from.

The credentialing protocols are being incorporated into hardware devices—cameras and smartphones—specifically so that the future viewer can accurately determine the date, time, and location of a photo at the point of capture. The same technology is already part of Photoshop and other editing programs, allowing edit changes to a file to be logged and inspected.

All that information pops up when the viewer clicks on the “cr” icon, and in the same clear format and plain language as a nutrition label on the side of a box of cereal.

Were this technology fully in use today, news photo editors could have reviewed the Content Credentials of the Royal Family’s photo before publication and avoided the panic of retraction.

That’s why the Content Authenticity Initiative is working towards global adoption of Content Credentials, and why media companies like the BBC are already gradually introducing these labels. Others, like the AP and AFP, are working to do so later this year.

Universal adoption of this standard means that, over time, every piece of digital content can eventually carry Content Credentials, creating a shared understanding of what to trust and why. Proving what’s real—as opposed to detecting what’s false—replaces doubt with certainty.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com