During a recent campaign-style speech at the Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC), former President Donald Trump added a new twist to his usual anti-immigrant discourse by suggesting that immigrants coming to the United States are speaking “languages that nobody in this country has ever heard of.”

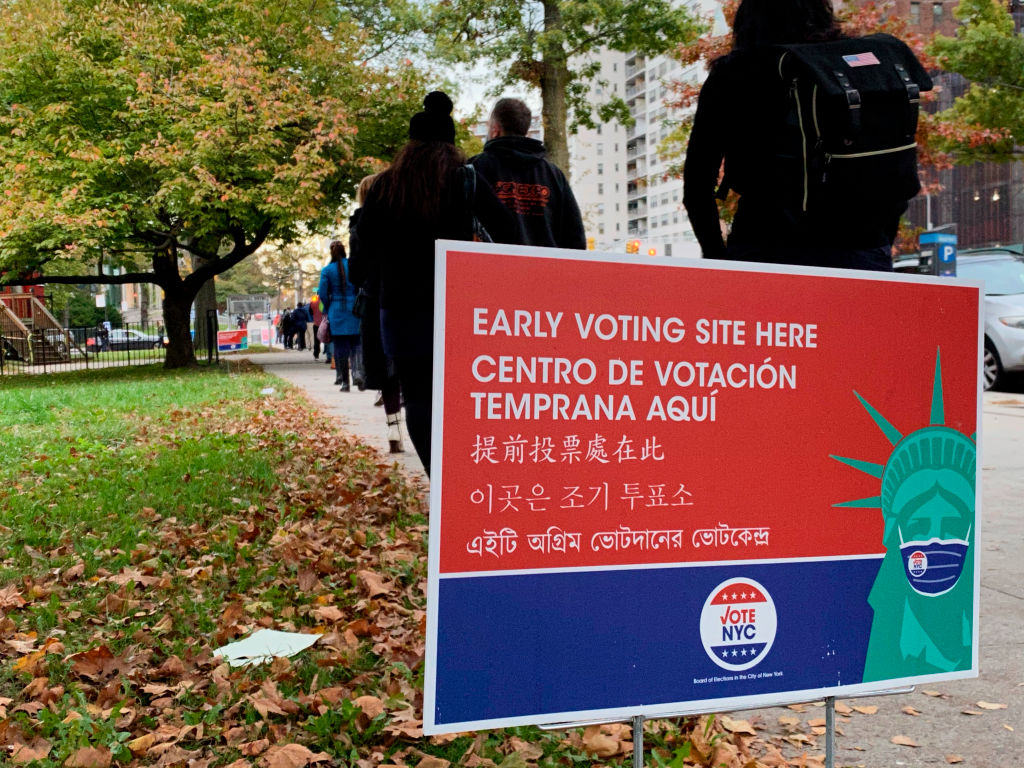

The implication in Trump’s statement is that linguistic diversity is a threat. This argument is not new. While the United States does not have an official language and more than 350 languages are currently spoken here, political debate over the use of languages other than English is nearly as old as the United States itself.

History shows us that the United States has been a reluctantly multilingual society, often pursuing linguistic assimilation instead of capitalizing on its natural linguistic diversity. Far from being mysterious and dangerous, multilingualism strengthens the economy and builds international connections.

Read More: I Rejected Spanish As a Kid. Now I Wish We’d Embrace Our Native Languages

From the time of independence, the United States has been a multilingual society. In addition to the hundreds of indigenous languages spoken prior to the first contact with European explorers and settlers, more than a quarter of all early settlers were non-English speaking. As the United States expanded, through the Louisiana Purchase and the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, it added both territory and vast numbers of speakers of French and Spanish.

Although often punished for speaking their own languages, many enslaved peoples brought against their will to the United States fought to maintain their native languages and created new mixed creole languages, adding to the linguistic diversity of the republic. Subsequent waves of immigration after the Civil War brought huge numbers of speakers of Scandinavian, Slavic, and Romance languages.

But the United States also has long had an uncomfortable relationship with its multilingual population. Rooted in the idea that linguistic diversity represents an obstacle to national unity, former President Theodore Roosevelt once wrote, “We have room for but one language in this country, and that is the English language.” Both local and federal campaigns sought to stamp out “foreign” and indigenous languages, particularly in times of national conflict and uncertainty.

Following the Spanish-American war, English was gradually imposed as the dominant language in schools across the newly acquired Puerto Rican territory. On the heels of World War I, a turn in public sentiment led to the closure of German-language newspapers across the Midwest and a drastic decrease in the number of students studying German. Following World War II, Japanese language schools in Hawaii were forced to close. Across the United States and Canada, residential schools established for Native and First Nations children imposed English as the sole language, often physically punishing children who dared speak a language other than English.

Time and time again, the goal of these initiatives was to promote cultural and linguistic assimilation by using language as a nationalistic unifying characteristic. But, there are economic and political consequences to demonizing rather than embracing linguistic diversity.

Indeed, countries that have embraced their multilingualism have experienced financial success, helping businesses secure more contracts and individuals earn higher salaries. Switzerland, for example, attributes more than 10% of its GDP to the fact that it is a highly multilingual society. Experts suggest that the ability to conduct business in multiple languages, and notably languages other than English, builds successful business relationships and creates a clear competitive advantage. In contrast, experts suggested that Britain in the pre-Brexit era was forgoing an additional 3.5% of its GDP due to a lack of multilingual skills in its workforce.

From a political perspective, a strong national multilingual foundation helps facilitate global relationships and policy goals. In fact, the United Nations cites multilingualism as a fundamental value in international diplomacy, contributing to communication that is more “impactful and meaningful.”

A lack of linguistic diversity has contributed to some recent policy failures. For example, the U.K. Parliament’s Foreign Affairs Committee cited a lack of Russian speakers in the Foreign Office as being partially responsible for its inability to predict Russian movements in Ukraine following the annexation of Crimea.

There is also a real danger in creating a broad mistrust of linguistic diversity, as it weaponizes language in service of discriminatory, anti-immigrant rhetoric. Viral videos and news stories highlight the harassment of people in the United States speaking a language other than English, with insults like “go back to your own country” and “speak English, you’re in America.” Yet, the importance that people place on the English language in the United States varies across the political spectrum. A 2020 survey by the Pew Research Center showed that Republicans are more likely than Democrats to say that speaking English is important for being “truly American.” Agreement was highest (92%) among self-identified conservative Republicans, the demographic that forms much of Trump’s base.

In his speech, Trump overlaid a fear of linguistic diversity on top of his standard anti-immigrant rhetoric, using the perceived links between language and nation to stoke further mistrust of immigrant communities. By highlighting minority languages that “nobody” has ever heard of, Trump attempted to add an additional degree of suspicion.

But such warnings are rooted in fear, not history or reality. Our reality is that the United States has been multilingual from its inception. Far from being something to fear, multilingualism makes the U.S. stronger — economically, politically, and culturally — and should be nurtured and celebrated. As Trump said, “languages are coming into our country,” but that’s a good thing.

Daniel J. Olson is a Professor of Linguistics and Spanish at Purdue University and the director of the Purdue Bilingualism Lab.

Made by History takes readers beyond the headlines with articles written and edited by professional historians. Learn more about Made by History at TIME here. Opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of TIME editors.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Daniel J. Olson / Made by History at madebyhistory@time.com