In January, the Department of Justice released its report assessing law enforcement failures in the horrific attack on Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas. The 2022 shooting caused the deaths of 19 children and two staff members, and law enforcement agencies have been widely criticized for lack of coordination and delays in response. The DOJ's 610-page Critical Incident Review documented a devastating “lack of urgency” overall at the scene.

As with this and other mass shooting tragedies, investigators may draw upon the accounts of the perpetrator’s family and friends to understand the attack and how to prevent future shootings like it. But those vital perspectives can sometimes be hidden from public view. The history of Kathy Leissner, the wife of University of Texas-Austin mass shooter Charles Whitman, reveals that Americans have much to learn from those who may share a household, a bank account, or a bedroom with a violent person before he turns his gun on the public.

Read More: Justice Department Report Finds 'Cascading Failures' and 'No Urgency' During Uvalde Shooting

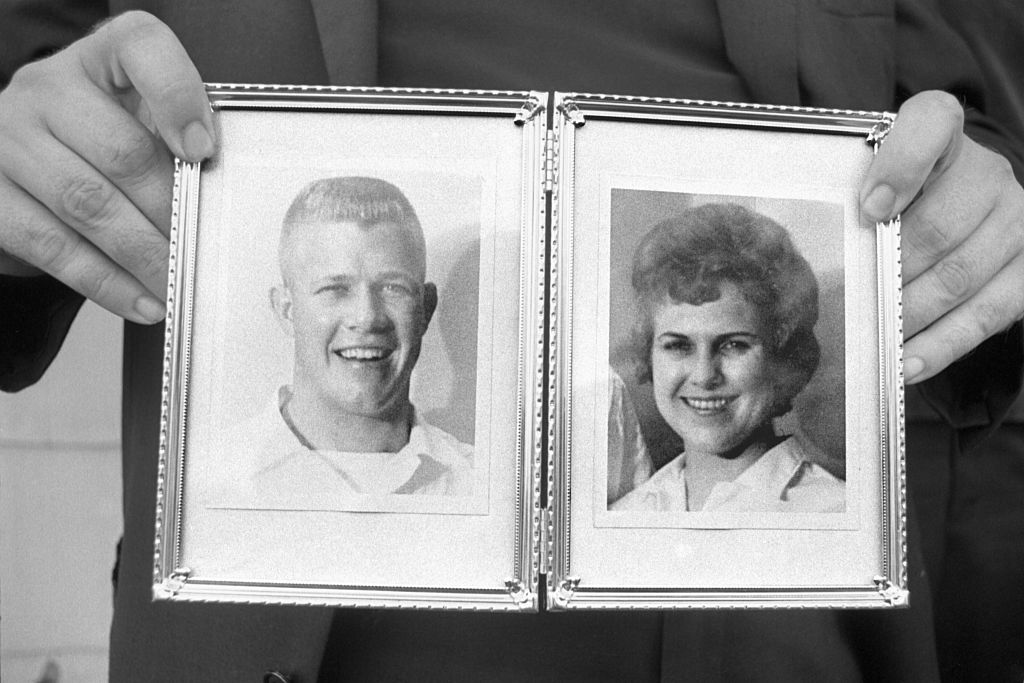

The massacre at the University of Texas at Austin occurred in 1966, when student and ex-Marine Charles Whitman took his guns to the university’s clocktower and fired at people on the campus below, killing 14 and wounding 32 people (one person would die later of complications related to a gunshot wound). A week after the shooting took place, a Travis County Grand Jury declared that Whitman was an individual who had “suddenly gone completely berserk, with no warning to his family or friends.”

But the Travis County Grand Jury was missing crucial information. Although acknowledging that Whitman had first killed his mother and then murdered his 23-year-old wife in the hours leading up to the shooting, the jury—like most Americans even today—did not recognize that domestic murders represent the far end of a continuum of ongoing abuse rather than a sudden or random incident. And there had been signs, even if they weren’t apparent to the jury. In 2015, I was granted access to a private archive, not publicly accessible to other researchers, containing roughly 600 personal letters between Charles Whitman and his wife Kathy Leissner, and between Leissner and other family members, which documents the years of abuse that Whitman inflicted on his wife behind closed doors. Leissner’s eldest surviving brother, Nelson, had protected and preserved these documents for five decades before allowing me permission to study them.

Read more: Why So Many Mass Shooters Have Domestic Violence in Their Past

Kathy Leissner’s history prior to her marriage reminds us that, even in the 1960s, there was no “typical” victim of abuse. Before entering the University of Texas in 1961, she had grown up in a small rural community southwest of Houston. She was the eldest child and cherished only daughter of prosperous working parents, both with college degrees—her father a rice farmer and cattle rancher, her mother a teacher. Capable and diligent as a student, vibrant and socially intelligent as a friend, Leissner thrived in various high school activities from volleyball to the student newspaper, from band to the Honors Society. She learned to drive a rice truck, how to herd cattle, and how to spray them for bugs. From an early age, she was an avid documentarian, jotting notes, collecting mementos, and annotating photographs in a scrapbook to make a record of her joys and curiosities.

Leissner had known Charles Whitman for roughly nine months when they got married. Charmed by his good looks and a whirlwind courtship, she agreed to his proposal and they were wed in August 1962. But his superficial charms camouflaged his misogynistic attitudes and bullying tendencies. Her new husband’s dominating treatment surfaced almost immediately.

By February 1963, after he lost a college scholarship, Whitman pressured Leissner to drop out of college herself and move away from Texas. Once they’d moved, he sought to isolate her from her friends and family, prohibiting her access to a telephone. However, with the assistance of her mother, Leissner managed to escape, return home, and re-enroll at UT on her own while her husband completed his military service. During their separation, letters show that he monitored her body obsessively, requiring she adhere to exacting physical standards, and when they were together during his leaves, he pressured her to get pregnant. He controlled his wife’s spending even as he violated military rules against gambling. His letters, as well as hers, show that he was emotionally abusive and physically violent. When she spoke up, he gave rote apologies or blamed her for his actions, and his behaviors didn’t change.

Read More: Misogyny Is a Precursor to Terrorism

In her short life, Leissner struggled to navigate common patterns of intimate partner abuse during a time before domestic violence was well understood. Her husband exploited her loyalty and her deep sense of personal responsibility. Phone hotlines for abuse survivors did not yet exist, and one of Texas’ first shelters for “battered women,” located in Austin, would not open until 1977. Without access to no-fault divorce, not legal in Texas until 1970, Kathy would have had to fight her controlling spouse in court to justify reasons for reclaiming her freedom.

Leissner wrote many letters to her husband to communicate her deepest needs and her hopes for the future. Her responses to him reveal a great deal about the violence she experienced and the survival strategies she used. Some letters communicated heart-wrenching despair. At one point, she struggled to reason with Whitman after he had attacked her for crying. “What do you call a genuine reason for tears?” she wrote. “I cry when I need to, not to gain sympathy, my way, or your attention.” From the relative safety of temporary distance, she also frequently challenged him. Upon learning of his arrest and pending court martial as a Marine in 1963 for threatening another serviceman, having an unauthorized firearm, and loan-sharking, she wrote: “[I]f we are going to make anything out of our marriage, there are going to have to be some powerful changes as far as I can see.”

Through her four years of marriage, Leissner fought to affirm her own agency and independence. She worked multiple jobs, eventually finishing her college degree. She earned a teaching credential and, then, a full-time position as a high school science teacher.

But despite every possible effort, Leissner’s once-bright spirit was worn down by Whitman’s cruelty and the sense that, try as she might, she could never satisfy his ever-shifting demands and expectations. “How do you apologize for something you can’t name?” she wrote in 1964, struggling to address one of her husband’s tangled criticisms. “It’s something I didn’t do and should have, and then again it is something I did.”

When the couple was finally reunited in the last year of her life, Leissner began, tentatively, to break the seal of secrecy and shame that abusers rely on. Between 1965 and 1966, it seemed she was planning to escape the relationship for good. She asserted some private independence by opening a new bank account in her name (it is unknown whether Whitman knew about it). She also began acknowledging her fear and used the word “divorce” with her friends and parents, imagining the possibility of a new life.

But it would not be. Leissner’s future was brutally stolen away in the dark morning hours of Aug. 1, 1966, when Whitman stabbed her to death in her own bed.

And within hours, he would lug a trunk of weapons and supplies to the top of the Texas Tower and wreak mayhem on an unsuspecting community.

Read More: Supreme Court to Decide Whether Some Domestic Abusers Can Have Guns

Fifty years later, it is not much easier for witnesses in private pain to be heard and recorded. Stigma and fear of blame still lead many survivors to withhold their stories. Women who do sound the alarm are often not taken seriously, with harrowing consequences. Many learn to cope by downplaying the gravity of their experiences until it is too late to raise a red flag.

It is inadequate merely to acknowledge that most mass shooters harm or kill an intimate partner or family member prior to—or as part of—their public crime. On his way to murder 19 children and two adults at Robb Elementary School, the Uvalde killer shot his grandmother, Celia “Sally” Gonzalez, and left her for dead. Before that day, he had threatened female co-workers and had an extensive history of directing graphic and disturbing content at young women online.

Far from suddenly “going berserk,” perpetrators often rehearse their abuse in settings with people who are socially expected to endure it, as was the case with Kathy Leissner Whitman.

In an age when threat assessment experts emphasize the need for de-escalation, disruption, or even prevention of violent events, we must also make it possible for people to share, without shame, the abuse they witness or experience. Kathy’s voice, one among thousands of unheard victim-survivors, offers a prescient testimony about the price we pay for a lack of understanding. Together, we can become more educated about how to hear and recognize the signs hiding in plain sight.

Jo Scott-Coe, Professor of English at Riverside City College, is the author of Unheard Witness: The Life and Death of Kathy Leissner Whitman (University of Texas Press).

Made by History takes readers beyond the headlines with articles written and edited by professional historians. Learn more about Made by History at TIME here. Opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of TIME editors.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Jo Scott-Coe / Made by History at madebyhistory@time.com