Prabowo Subianto, a former general who was once banned from entering the United States because of alleged human rights abuses, looks set to become the next President of Indonesia, according to preliminary results hours after the Southeast Asian country of 270 million people voted on Wednesday in the world’s largest single-day election.

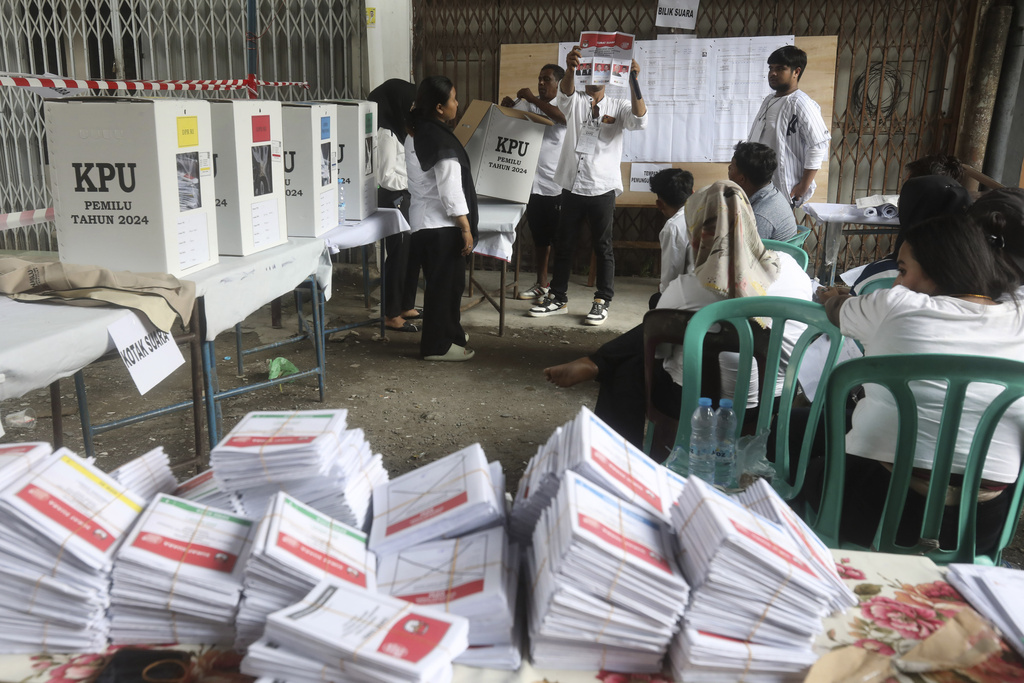

Despite some weather concerns, election officials said voting went smoothly across the more than 800,000 polling stations throughout the vast archipelago that spans thousands of islands. According to unofficial counts by independent agencies, Prabowo is on track to win with nearly 60% of the vote, while authorities are expected to validate the results in the coming weeks.

Read More: The Ultimate Election Year: Half of World Heads to Polls in 2024

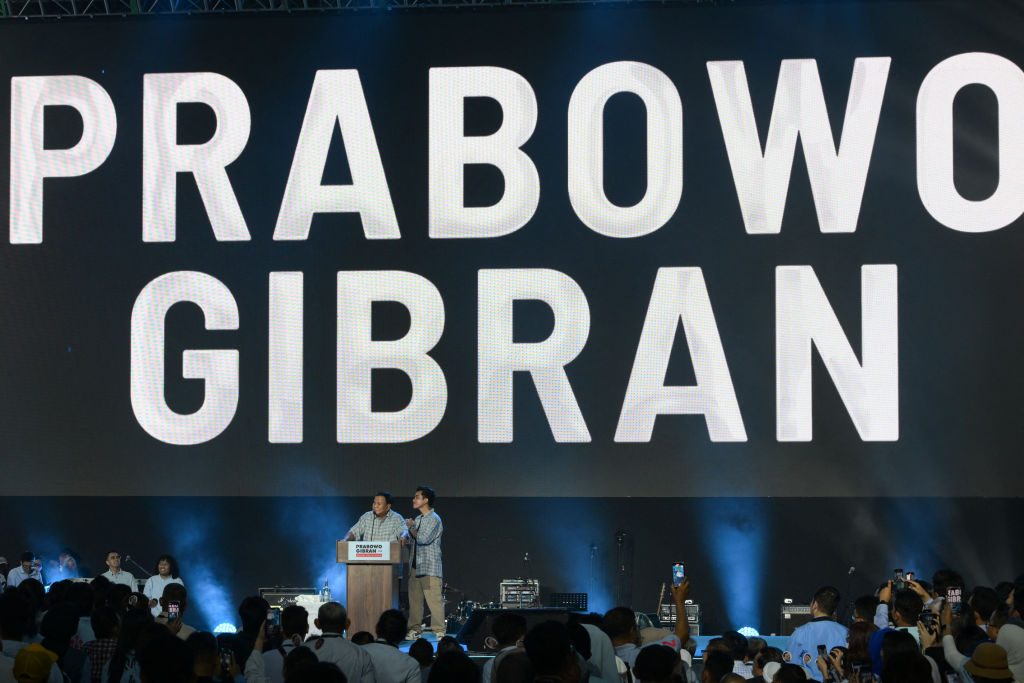

“Even though we are grateful, we can’t be arrogant,” Prabowo told a crowd of supporters at a stadium in Jakarta during an election night celebratory rally. “We must remain humble,” he said.

The decisive victory comes as little surprise: While opinion polls had for much of the campaign season predicted the election would go to a run-off between Prabowo and one of his two rival candidates—either independent former Jakarta Governor Anies Baswedan or former Central Java Governor Ganjar Pranowo from the ruling Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P)—early February saw the tide turning in Prabowo’s favor with late forecasts suggesting he would likely secure a majority of votes to win outright. (The PDI-P nevertheless leads early vote counts for seats in parliament.)

The presidential election, however, forebodes a fresh era of uncertainty for Indonesia’s fledgling democracy.

Prabowo rose to prominence as a military commander during the rule of his then father-in-law, the late former President Suharto, who ruled the country from 1967 to 1998. Under Suharto’s repressive regime, Prabowo was known as one of the authoritarian leader’s chief enforcers, implicated in the abduction and alleged torture of dissident activists. Following his 1998 ouster, Prabowo turned to business, amassing a significant fortune before venturing back into politics. In 2008, he co-founded the nationalist, right-wing Gerindra Party, which he currently leads. He also ran for the presidency in 2014 and 2019, but lost to incumbent President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo both times, after which he joined Jokowi’s administration as Defense Minister.

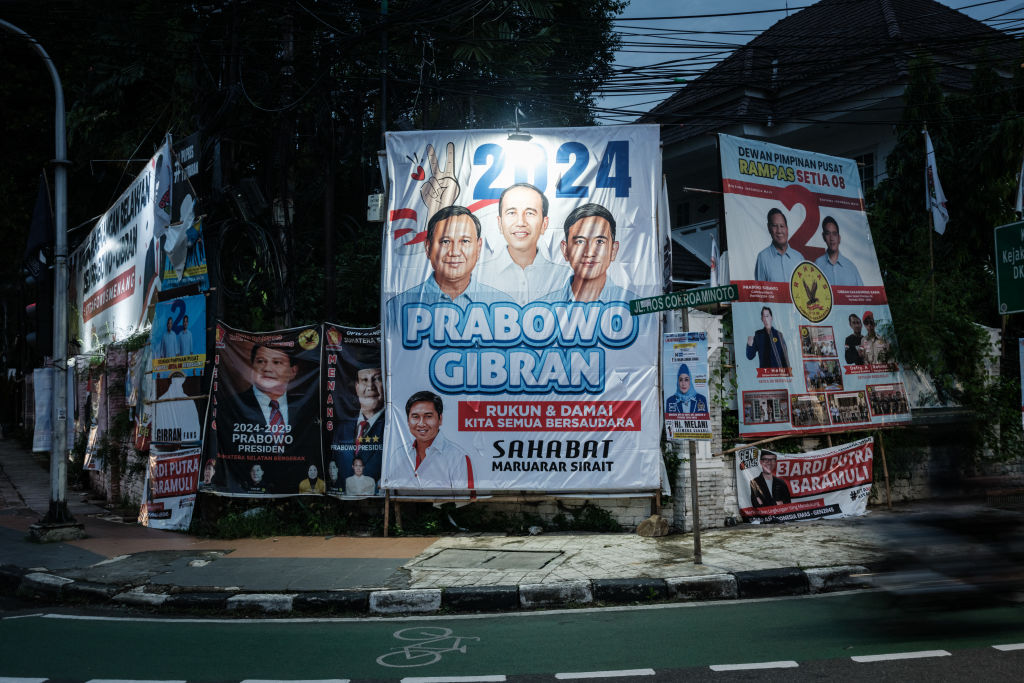

But the 72-year-old’s newfound success is tainted with controversy. For one, his vice presidential running mate Gibran Rakabuming Raka, 36, is Jokowi’s son, whose candidacy was only approved after a contentious ruling by the country’s constitutional court, which was headed by Jokowi’s now-dismissed brother-in-law. The 2024 presidential race was largely seen as a referendum on the legacy of Jokowi, who, though he did not officially endorse any candidate, made no secret of his preferred pick amid a wider attempt to retain influence and build his own political dynasty.

Recent weeks have also seen mounting, albeit unproven, allegations of Jokowi-backed electoral rigging in favor of the Prabowo camp. Over the weekend, a documentary titled Dirty Vote was posted on YouTube that detailed alleged election fraud by the Jokowi administration; it racked up millions of views within a day and became the top trending topic on X. The allegations in the video were denied by Prabowo’s campaign, but Jokowi’s former vice president Jusuf Kalla told media that “most of it is indeed the truth.”

As votes were tallied on Wednesday, Prabowo’s opponents alluded to similar concerns about election integrity. Former President and PDI-P chair Megawati Sukarnoputri urged the public to monitor for potential fraud, while Anies told Al Jazeera Wednesday after the polls closed that he could not yet tell if the election had been free and fair, with his team later saying they found “many violations” such as vote tampering. (In 2019, Prabowo had rejected the election results, alleging voter fraud, a claim authorities deemed “baseless.”)

At a press conference Wednesday night, the general elections commission said re-voting has occurred or would occur at 668 polling stations across the country—some due to “security disturbances” where equipment was damaged or documents mixed up, others due to flooding or a shortage of ballot paper.

Presuming the result stands, all eyes in the country—including Jokowi’s—will now be watching to see if Prabowo, a former Jokowi rival, will honor his campaign promises to continue his predecessor’s populist policies, or if he will give in to his authoritarian tendencies.

But either way, experts tell TIME, whereas Jokowi’s election 10 years ago was hailed as a triumph of democracy in the world’s fourth most-populous country, Prabowo’s rise coincides with a dangerous plummeting of public trust in the country’s political system.

“The procedural side of delivering elections [in Indonesia] has always been very good and there's always been high public trust in it,” Ian Wilson, a senior lecturer specializing in Indonesian politics at Australia’s Murdoch University, tells TIME. “But this time, a lot of people are very suspicious about this process on all sides.”

“There’s clearly an atmosphere that’s been generated that’s very bad for democracy overall,” Wilson says, adding that no matter who won the election, “there’s going to be a big chunk of the population who are going to see it as illegitimate in one way or another.”

Strongman and “cute grandpa”

Prabowo’s image as a strongman has served him well among much of the Indonesian population, experts say. “The particular idea of strong leadership, even aggressive leadership, is often seen very positively by many people in the country,” says Wilson, “to kind of rein in the undisciplined and unruly aspects of Indonesian socio-political life. So the country can move forward.”

But his presidential bid also owes much of its success to a social media rebranding campaign featuring his beloved felines, a cherubic AI avatar, and TikTok dances that have drawn large swathes of youth to his “gemoy” persona, an Indonesian term referring to something that’s cute and cuddly.

Judging by his social media pages, it could almost seem as if Prabowo’s previous life as a fearsome general never existed. But not all have forgotten about his dark past, with protests against Prabowo’s alleged human rights violations breaking out during his campaign. For months, anxiety swelled among activists and civil society about what Prabowo’s victory would mean for civil liberties in the country, which has already seen a period of democratic decline under the Jokowi administration.

But apart from Prabowo’s most vocal critics, younger supporters say they want to move on from his disgraceful past and judge him by his response to the country’s unemployment and economic issues; others have taken to his populist promises, most notably a 460 trillion rupiah ($29 billion) plan to distribute free school lunches across the country.

No forever friends—or foes

Prabowo’s populism is intentionally reminiscent of the massively popular Jokowi. Where he had in previous campaigns pitched himself as the antithesis to Jokowi, this time Prabowo vigorously touted himself as a candidate of continuity, promising to keep up Jokowi’s pet projects like a focus on nickel mining and the ambitious construction of Nusantara, a new capital for the country.

It certainly helped Prabowo that he received noticeable support from the incumbent himself, who, having risen from humble roots outside elite political circles to the government’s top job, became something of a folk hero in Indonesia. While Jokowi did not officially endorse any candidates, he was spotted dining out with Prabowo, he traveled to Central Java (rival candidate Ganjar’s home province) to hand out cash and rice, and he even lent his face to campaign posters alongside Prabowo and Gibran.

In a country where it’s rare for sitting presidents to actively campaign for their successor, Jokowi’s chumminess with Prabowo raised eyebrows—and perhaps more crucially, cost him key allies and supporters. Amid claims by rival campaigns of being harassed by state security forces, there have also been rumors of fissures within the cabinet and speculations of the resignations of top officials, with allegations of interference against Jokowi culminating in a long-shot impeachment petition.

Jokowi’s partnership with Prabowo comes as the President, who has neither a strong political vehicle to remain relevant nor the financial resources of an oligarch, has latched onto the former general as a way to cling to power even as his presidential term ends in October.

But it remains to be seen whether the gambit will pay off. Recent maneuvers have seen Jokowi “lose the confidence” of civil society and activists who had backed him in 2014 and 2019 to combat Prabowo, Vishnu Juwono, associate professor in public governance at the University of Indonesia, tells TIME. And “there’s still a question mark” over whether Jokowi will even be able to exact influence through a Prabowo presidency.

Prabowo has shown little qualms about switching his political allegiance—he has a famous decadeslong, on-again-off-again friendship with Megawati, and in 2019 he turned his back on his previous hardline Islamic support base to seek ties with Jokowi. His current truce with longtime rival Jokowi exemplifies the dealmaking that has characterized Indonesian politics, observers say, where there are neither forever friends nor permanent foes.

“It is quite risky, and it seems largely based on some kind of trust that Prabowo will do what he says, and that seems to me quite a naive assessment,” says Wilson. “But then again, Jokowi has been relatively astute throughout his career.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- L.A. Fires Show Reality of 1.5°C of Warming

- How Canada Fell Out of Love With Trudeau

- Trump Is Treating the Globe Like a Monopoly Board

- Bad Bunny On Heartbreak and New Album

- 10 Boundaries Therapists Want You to Set in the New Year

- The Motivational Trick That Makes You Exercise Harder

- Nicole Kidman Is a Pure Pleasure to Watch in Babygirl

- Column: Jimmy Carter’s Global Legacy Was Moral Clarity

Contact us at letters@time.com