On Thursday night, Kate Cox is set to sit in the President’s box as a guest of First Lady Dr. Jill Biden at the State of the Union Address. Her presence reflects the importance of abortion as a political and electoral issue, as well as her willingness to speak up for access to medical care.

The 31-year-old mother of two could have stayed quiet and anonymous after learning her fetus had the highly fatal trisomy 18 and doctors warned her that her pregnancy threatened her life and future ability to have children. Cox could have traveled from her native Texas—where abortion is banned—to another state for the abortion that she needed, with no one but those closest to her knowing about it. However, Cox desired to have the medical procedure at home with her own doctor and family nearby, so she sued Texas for the right to terminate her pregnancy. She aimed to force the courts to define when an abortion is medically necessary, even if only in her case. The resulting uproar catapulted Cox’s nonviable pregnancy into the national spotlight.

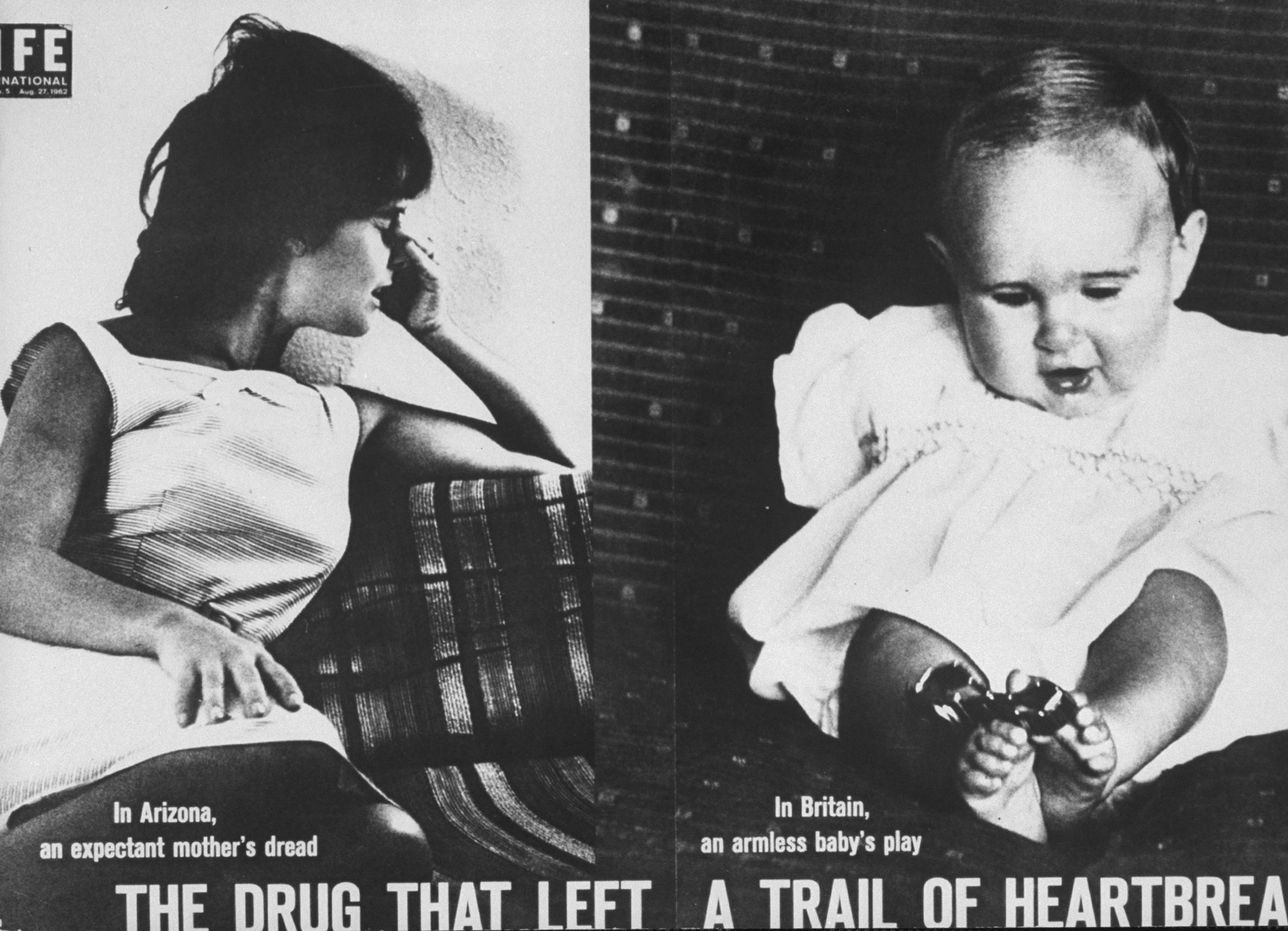

Cox’s story echoes the 1962 case of Sherri Chessen (she was known publicly by her husband’s name, Finkbine), whose abortion drew national and international scrutiny. Looking at the two cases side by side exposes the cruelty of abortion bans, then and now, and reveals how any claim that they protect mothers and children is a guise based on no applicable medical truth.

During the late 1950s and early 1960s, doctors across the world routinely prescribed thalidomide to pregnant women in attempts to ease nausea. Unbeknownst to anyone taking or prescribing the new drug, however, thalidomide often caused fetal anomalies when consumed during pregnancy and resulted in the death of around 40% of babies affected.

In 1962, Chessen, a mother of four, was pregnant for the fifth time, and consumed thalidomide regularly during the early weeks of her pregnancy, unaware of its impact on her growing fetus.

Read More: Court Says Texas Can Ban Certain Emergency Abortions. What That Means

In her 11th week of pregnancy, Chessen learned about the dangers of the drug. In consultation with her OB-GYN, she sought a therapeutic abortion—a procedure that she never expected to need—at Good Samaritan Hospital in Phoenix. She also spoke to the press anonymously to warn other women about thalidomide. But the press coverage ignited public outrage over the fact that Chessen planned to obtain an abortion, prompting the local newspaper to reveal her identity.

The story drew the attention of Maricopa County Attorney Charles N. Ronan, who said that under Arizona law an abortion could only be administered to “save the life of the mother.” Without learning the facts of the case, Ronan threatened to prosecute anyone who helped Chessen obtain an abortion. He claimed his office would have “no choice” if someone filed a complaint against her or her doctor since this was, in his words, “a medical question, not a legal question.”

Ronan’s statements had a chilling effect. Good Samaritan Hospital would not greenlight the procedure without immunity, despite Chessen signing a consent form agreeing that the abortion was “necessary for the protection of [Chessen’s] life and well-being.” At the time, doctors had little idea when prosecutors and courts would accept their judgment that a woman’s life was endangered, and when they would reject it. So the hospital sued on behalf of itself, Chessen, and her husband, Robert Finkbine, in an attempt to force the courts to “define life.”

But a judge refused to offer criteria for defining when a woman’s life was at risk—instead claiming the definition of life was up to the doctors—and he dismissed the case. Despite the judge saying the matter was for doctors to decide, when reporters asked Ronan if he would prosecute the hospital, doctors, or Chessen if she received an abortion, he answered—with a sly grin on his face—“we’ll have to cross that bridge when we come to it.” Ronan’s convoluted and confusing answers created doubts in the minds of Chessen’s doctors, and they refused to perform the abortion for fear of both legal and social ramifications.

Even worse, vigorous news coverage of the situation shattered Chessen’s privacy. Newspaper headlines ranged from details about her pregnancy (“Pill May Cost Woman Her Baby”) to analysis of Chessen’s appearance and mental state (“Anguished Mother of 4 Awaits Operation Ruling”). One newspaper article shared Chessen’s home address, and her family began receiving hate mail and death threats, prompting a subsequent headline about Chessen’s plans (“Finkbines Slip into Seclusion”).

The courts’ refusal to intervene and the hospital’s unwillingness to permit the procedure forced Chessen to travel 5,000 miles to Stockholm, where, after a series of evaluations and weeks of waiting, she was finally able to get the legal healthcare she needed. Subsequently, she had two more daughters (one of whom, Kristin Atwell Ford, contributed to this essay).

Cox’s case featured many similarities to Chessen’s. Her doctor, too, thought an abortion was the appropriate medical care given the condition of her fetus and concerns about the risks of infection or uterine rupture. And this convinced Travis County District Judge Maya Guerra Gamble that Cox’s pregnancy put her “life, health, and fertility” at risk. But as with Ronan, Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton immediately struck back, writing in a letter that the judge was “not medically qualified to make this determination.” He claimed that Cox’s doctor did not show “all of the elements necessary to fall within an exception to Texas’ abortion laws.” Paxton also warned of prosecution against Cox’s doctors and their hospitals, writing that the judge’s order “will not insulate you, or anyone else from civil and criminal liability,” which could include prison time and hefty fines.

Read More: What to Know About the Texas Woman Who Sued the State to Get an Abortion

Like the judge and prosecutor in Chessen’s case, Paxton clung to the claim that the decision as to whether an abortion was necessary should be left to doctors—even as he refused to defer to Cox’s doctor’s judgment. Paxton also would not offer clarity on when a woman’s life was sufficiently at risk under the law to justify an abortion. This forced Cox to travel to New Mexico for an abortion. Before doing so, however, she rhetorically wondered, “Why should I or any other woman have to drive or fly hundreds of miles to do what we feel is best for ourselves and our families, to determine our own futures?”

Anti-abortion-rights forces claim that abortion bans aim to protect the wellbeing of mothers and families. But the long, tortured processes that confronted Chessen and Cox after finding out that an abortion was medically necessary reveal that those claims are false. The point of abortion bans is to make it harder for anyone to obtain terminations, including when there are fatal fetal anomalies or when the life of the mother is at stake. Even pundit Ann Coulter, a conservative abortion opponent, argued that the decision not to allow Cox to terminate her pregnancy lacked compassion.

The two cases also showed that stereotypes about abortion patients, as well as the outrage directed at Chessen and Cox, miss something fundamental. Both Chessen and Cox were mothers who wanted to have more children and were trying to safeguard their ability to do so. Chessen hoped to have six kids. She was concerned about her ability to care for her four living children and her future children. Arizona’s abortion ban, and the power arbitrarily exercised by Ronan, prevented her from having a procedure she desperately needed, and made an already agonizing ordeal even worse.

Cox also emphasized how her abortion was about protecting not only her health, but her ability to grow her family, “We want to be able to have more babies. We want to give siblings to our kids.” She also was shocked that the state was willing to “put [her] own health at risk and a future pregnancy at risk.”

Now 91, Chessen still vividly remembers the death threats and public shaming she received for speaking up about her abortion. Still defiant decades after the threat of prosecution derailed her medical care, Chessen declares, “Sixty years later and [Cox] has to go through exactly what I went through? Somebody’s not listening, somebody’s not learning.” Chessen acknowledges how the trauma of the state blocking her abortion still haunts her: “It will never go away. Never, never, never. And no one should be put through that kind of torture.”

Saniya Lee Ghanoui is an assistant professor of history at the University of Texas at El Paso. Kristin Atwell Ford is an Emmy Award-winning filmmaker. Ghanoui and Atwell are producing a documentary about the impact of Sherri Chessen’s story on abortion laws, drug safety, and fetal health.

Made by History takes readers beyond the headlines with articles written and edited by professional historians. Learn more about Made by History at TIME here. Opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of TIME editors.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Saniya Lee Ghanoui and Kristin Atwell Ford / Made by History at madebyhistory@time.com