Heading into an uncertain U.S. presidential campaign, Florida governor Ron DeSantis branded the Walt Disney Company a "woke" corporation producing films that pursue a politically correct, LGBTQ+ agenda. A so-called “exclusively gay moment” in the live-action Beauty and the Beast, a same-sex kiss at the end of Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker, and an out gay character in the animated Strange World all provided fuel for DeSantis’ stoking of the culture wars. Now that DeSantis has dropped out of the race, he has returned to Florida to continue his work as a culture warrior against Disney, higher education, and more. But what DeSantis fails to realize is that this isn’t Disney’s first “woke” moment.

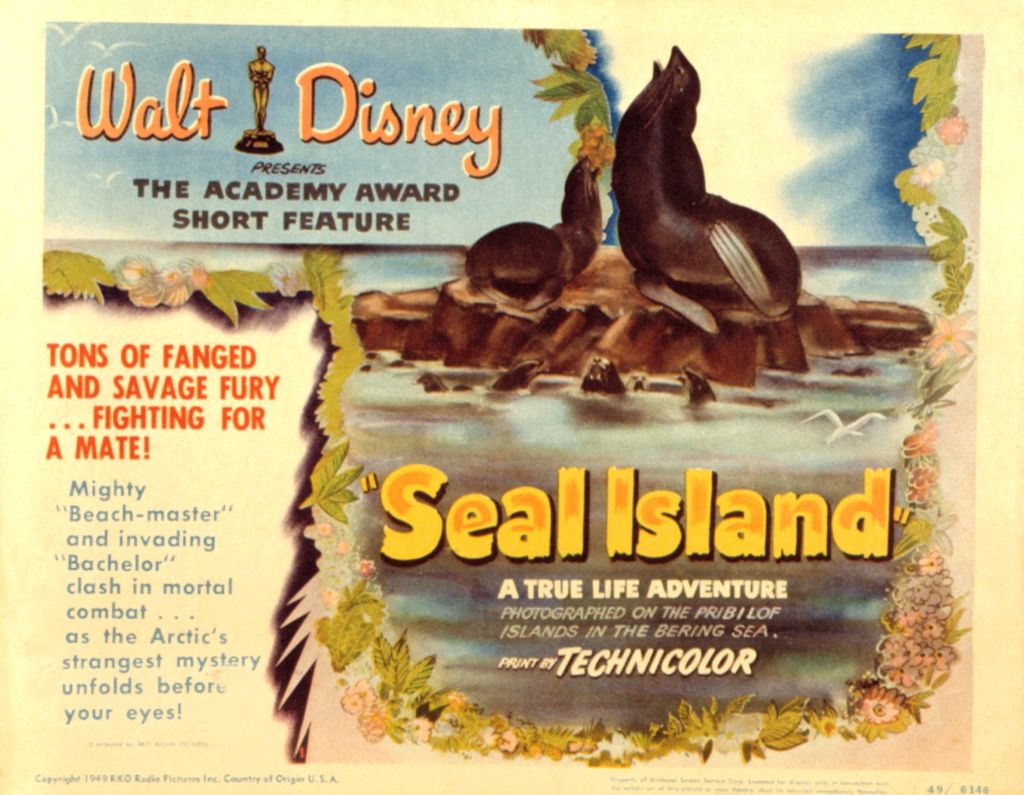

Seventy-five years ago, Disney Studios premiered Seal Island, a 27-minute film that directly challenged how Americans thought about the environment. Although Disney had garnered an international reputation for animated feature-length films, Seal Island was a live-action nature documentary that dared to depict animals as deserving compassion and respect.

Read More: Disney Versus DeSantis: A Timeline of the Florida Feud

Given the popularity of contemporary nature documentaries today, it’s difficult to imagine a time when wildlife films consisted mostly of safari expeditions and far-off travelogues that treated animals as expendable and exploitable. But in the first half of the 20th century, animals were mostly depicted as trophies to be hunted or threats to be eliminated.

Beginning with the release of Seal Island in 1948, the 13 documentaries that ultimately comprised Disney’s True-Life Adventures series shattered that archetype. The films encouraged viewers to empathize with creatures in the natural world, establishing animals as protagonists in dramatic stories that portrayed them as smart, nurturing, and even heroic.

Walt Disney drew on an environmental ethos he had established six years earlier, in 1942, with the release of the animated film Bambi. Conservatives had railed against that movie as sentimental nature-faking, with Outdoor Life editor Raymond J. Brown declaring it “an insult to American sportsmen” for depicting the shooting of Bambi’s mother, something that took place off-screen, and “Man’s” carelessness in setting the forest on fire.

As with many Disney films today, however, detractors could not suppress the public’s enthusiasm for either Bambi or Seal Island and its sequels. Between 1949 and 1959, the True-Life Adventures films earned Disney a remarkable eight Academy Awards and proved wildlife filmmaking’s commercial viability. Yet the movies’ greatest impact was in how they transformed Americans’ perceptions of nature, exerting a cultural influence “far wider than Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring or the Sierra Club,” as one commentator observed.

Read More: Giving Names to Cute Baby Animals Can Save a Species: Jane Goodall Explains

Disney’s naturalist photographers used live-action cameras with regular, telephoto, and close-up lenses for filming mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and insects in their natural habitats. They also shot dramatic sequences in controlled settings. The Studios’ production team edited the footage and, drawing on experience from making animated films, combined it with compelling—and often comedic—narratives and music.

The effect was mesmerizing, with one reviewer claiming the films marked “the new high point in Disney’s career as the man who has found in nature a…world and its creatures more wonderful than the imagination of the fairly-tale writers.”

While some film critics took issue with the way the Studios transgressed the movie’s claims to be “completely authentic, unstaged and unrehearsed,” the True-Life Adventures had the power of the Disney marketing machine behind them. Throughout the 1950s, they made their way first into movie theaters and then quickly into schools, churches, libraries, and living rooms across the nation. Educators clamored for them.

The way the films anthropomorphized animals was undoubtedly their most influential feature. Ascribing human traits to non-human mammals especially, Disney admonished his production team that “no condescending attitude was to be taken toward nature.” Creatures were to be viewed not as “dumb animals” but as “our friends, the wise animals.”

That cut both ways, however. Representing animals as characteristically human, the True-Life Adventures only occasionally depicted them as part of a fragile ecosystem over which humans had significant leverage. Portraying beavers as “industrious” and “stubbornly persistent” undoubtedly facilitated viewers’ affiliation with wildlife, but it did little to elucidate humanity’s place within—and power over—the biosphere.

Nevertheless, because the True-Life Adventures generated sympathy for animals, wildlife organizations celebrated them for influencing people’s attitudes towards the environment. In 1955, for example, the Audubon Society presented Disney with its award for rendering “distinguished service to the cause of conservation.”

Read More: The Forgotten Women Who Helped Shape the Look of Disney Animation

The True-Life Adventures series also ignited an explosion of wildlife films and television programming. In 1957, the BBC established its Natural History Unit. In 1963, NBC premiered its long-running series, Wild Kingdom. That same year, the National Geographic Society commended Disney as “a superb teacher of natural history, geography and history” and then launched its wildly successful series of specials, including “Miss Goodall in Africa” and “The World of Jacques-Yves Cousteau.” Later, in 1968, ABC capitalized on the success of the latter and premiered The Undersea World of Jacques Cousteau, the first underwater documentary television series.

Forty years later, in 2008, the Walt Disney Company came full circle by establishing the independent film studio Disneynature to produce nature documentary films.

Wildlife film has become a ubiquitous part of the television and motion picture industry. Over the past few years, approximately 130 original nature series aired across network and streaming services. Viewed collectively by tens of millions of people, these productions place much greater emphasis on humans’ impact on the environment than did Disney’s films. Yet by using popular culture to influence how Americans understood wildlife, Disney’s True-Life Adventures—which were nothing if not “woke” for their time—fueled a nascent environmental movement, launched a new genre of nature documentary filmmaking, and fundamentally changed people’s minds about the world they lived in.

Charles Dorn is the Barry N. Wish Professor of Social Studies at Bowdoin College and is currently researching a book on the history of environmental education in the United States.

Made by History takes readers beyond the headlines with articles written and edited by professional historians. Learn more about Made by History at TIME here. Opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of TIME editors.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Write to Charles Dorn / Made by History at madebyhistory@time.com