When Frozen conquered Hollywood in 2013, it also shattered expectations. The box-office champ was the Walt Disney Animation Studios’ first film to celebrate the bond between sisters, the first to employ a female co-director and the first to earn over a billion dollars. Yet as modern as the film and its upcoming sequel Frozen II might seem, the movies are firmly rooted in the studio’s feminist origins.

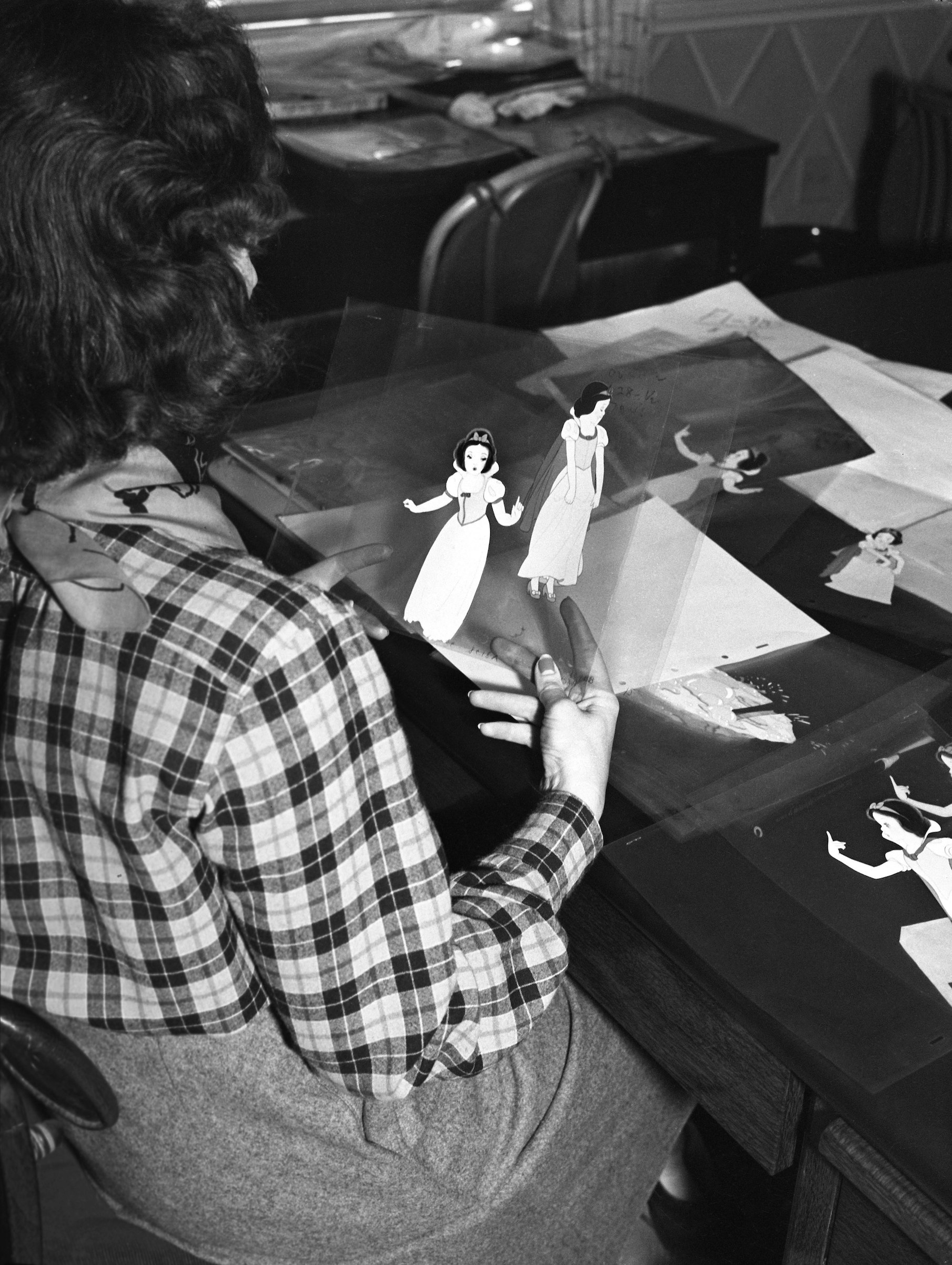

“The girl artists have the right to expect the same chances for advancement as men,” Walt Disney said to his employees in 1941, “and I honestly believe that they may eventually contribute something to this business that men never would or could.” Even as Disney said these words, rejection letters the studio sent to female applicants claimed otherwise. They stated clearly, “women do not do any of the creative work.” These words, while discouraging to many, were completely false: Walt had been hiring female artists into his story and animation departments since the 1930s. While most Hollywood animation studios of the time isolated their female employees in ink and paint departments, where women traced artwork in ink on sheets of celluloid before coloring between the lines, at the Walt Disney studios women were everywhere. There were women in the story department, drawing concept art, creating storyboards and seeking literature they wanted to portray on the silver screen. There were also women in the animation department, defining the look of characters and plotting the action between scenes.

Bianca Majolie was the first woman hired into the studio’s all-male story department in 1935. Her tenure would be marked with both triumph and prejudice. Majolie translated Le Avventure di Pinocchio from its original Italian, and then considered how to adapt the story for the screen. From the Collodi tale of a naughty, murderous wooden puppet, she infused the script with a deeper meditation on what it means to be human. Majolie would work on a wide range of films—selecting music for Fantasia, drawing concept art for Cinderella, writing material for Peter Pan and creating a sympathetic elephant character that would inspire Dumbo. Yet along with all her accomplishments came resentment from her male colleagues, who could be cruel in their criticism during story meetings. “I sat in the corner with my heart beating wildly and gasping for air,” she wrote in a letter to a friend about a particularly tense meeting. Ultimately Majolie’s career at Disney would abruptly end in 1940 when she returned from vacation to find her desk cleared out. No one had bothered to tell her she was fired.

Majolie was one of a powerful group of women who dominated the studio during its golden age, from 1930-1970. She worked alongside Sylvia Holland, a middle-aged widow desperate to keep her family afloat. As the first female story director, Holland worked closely with the visual-effects department, eager to shape Fantasia into a delicate rendering of art and nature. To this end, she brought her small group of artists, along with a member of the special-effects department, to the Idyllwild Nature Center in the San Jacinto Mountains east of Los Angeles. They were pushing the boundaries of effects animation, putting significant resources into making snowflakes swirl and dewdrops glisten, using an anomalous mix of metal shavings, small twinkle lights and hand-cut snowflakes gliding down an S-shaped track.

This technology would be improved upon in the studio’s upcoming feature, Bambi, as they began testing their artwork in the multi-plane camera, which added depth and realism to their scenes. The artists working on the film were gathered around a pile of mysterious sketches. No one knew where the drawings had come from, but all agreed that they were chilling. The hunting dogs seemed to leap off the page with thick, muscular bodies and arresting eyes. Everyone assumed the mystery artist was a man. Then Retta Scott walked in. Thanks to her terrifying sketches, and her plethora of ideas on how to make the animals even more frightening, she would become the studio’s first credited female animator.

Working alongside Scott was her best friend, the talented Mary Blair, hired by Walt Disney in 1940. Blair worked on early projects with Majolie and Holland before being sent on a trip to South America along with Walt Disney and a small group of artists for the film Saludos Amigos. It would be the first of many research trips for Blair, and the travel deepened her artistic sensibility. Walt cherished her work and soon made her art director for a host of films, including Cinderella, Peter Pan and Alice in Wonderland. Her bold, modern style defined Disney film in the 1950s. She also worked on several theme park projects, including the “It’s a Small World” ride for Disneyland. Yet after Walt’s death in 1966, the company never hired her again.

And Frozen is part of the story too. Its development began in 1938, with a treatment written by Mary Goodrich. Goodrich was a reporter for the Hartford Courant and an aviator who at age 26 completed the first female solo flight to Cuba. In addition to her work on Fantasia and Dumbo, Goodrich adapted The Snow Queen, written in the 1840s by Hans Christian Andersen. The task was not easy, as the tale consisted of seven fragmented stories and lacked a clear narrative. Yet it was impossible not to be entranced by its repeated themes of the redemptive power of love, and the triumph of vulnerable children over destructive adults.

In the mid-1990s, The Snow Queen was reimagined at the studio as an animated action-adventure film, one in which the villain, Elsa, freezes the heart of a poor peasant named Anna. The concept art showed an evil queen with blue skin, spiky hair and a coat made from living weasels—an icy Cruella De Vil. The film’s direction was still up in the air when someone said the magic word: “sisters.”

Along with the premise of sibling bonds came the renewed influence of the studio’s pioneers. Michael Giaimo, as art director for Frozen and Frozen II, found inspiration in artwork made 60 years earlier by the artists of Disney’s golden age. Surrounded by a diverse group of modern artists, and nurtured by the studio’s first “sister summit,” where female employees gathered together to reflect on their personal relationships with their siblings, the work of the studio’s female pioneers finally had an opportunity to flourish onscreen once more.

The work of these women surrounds us, even though many of their names have faded from our consciousness, often replaced by those of the men they worked with. They have shaped the evolution of female characters in film, advanced our technology and broken down gender barriers in order to give us the empowering story lines we have begun to see in film and animation today. For some working at Disney today, their influence is immeasurable. “What she did went beyond the project into a pure art form,” Giaimo says of Mary Blair, “It became art. It became a statement unto itself.”

Nathalia Holt is the author of The Queens of Animation: The Untold Story of the Women Who Transformed the World of Disney and Made Cinematic History, available now from Little, Brown and Company.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com