As the 2024 presidential campaign kicks into high gear, many observers have highlighted the bizarre nature of Donald Trump’s hold on the GOP. He’s poised to yet again capture the Republican nomination, despite a presidency and post-presidency laden with controversy, as well as facing 91 felony counts in four different cases. These are unusual circumstances to say the least. And yet, surprisingly, there is a striking parallel in American history.

Like Trump, 18th century Congressman Matthew Lyon from Vermont constantly attacked an allegedly elitist establishment and regularly—and gleefully—violated political norms. In fact, during his re-election campaign, he was arrested, and actually managed to keep his seat despite being in jail. Lyon’s story offers clues to Trump’s continued appeal and why it might take a switch in strategies from his opponents to defeat him.

Though Lyon’s political career bears striking resemblances to Trump’s, his origins are much humbler. Lyon came to North America from Ireland as an indentured servant in 1764. During the War of Independence, he found riches by buying up Loyalist-surrendered property.

In 1797, he ran for a seat in the House of Representatives. Lyon campaigned as a political outsider and anti-elitist who spoke for “the industrious part of the community” and would counter the agenda of the “set of aristocrats” who populated government. Vermont voters rallied to this vision and sent Lyon to Congress.

Read More: President Trump Is Looking for Suggestions for Pardons. So We Asked 7 Historians for Their Thoughts

Once there, Lyon mocked the pomposity of his colleagues — refusing to participate in their rituals and traditions. For instance, he successfully put forward a motion to excuse those congressmen who did not wish to participate in the regular ceremonial procession to the president’s residence to thank him for his address to Congress. Lyon dismissed the procession as “vain adulation” and “pageantry.” This solidified his reputation as a man of the people, immune to the posturing, corruption, and backdoor-dealing of politics.

He was also prone to outrageous behavior. During the 1798 winter congressional session, Connecticut Congressman Roger Griswold insulted Lyon during a break in the official proceedings. Lyon responded by spitting in his face. Lyon’s opponents immediately clamored for his expulsion from the House. He must be removed from Congress, one man insisted, “as citizens removed impurities and filth from their docks and wharves.” The press likewise fixated on Lyon’s shocking lack of decorum and unfitness for office, nicknaming him “the spitting Lyon” and claiming that he acted no better than a common beast.

Meanwhile, Lyon’s backers cheered his audacity and unwillingness to be trampled upon by the elite. They were further gratified when the House’s expulsion resolution fell short of the required two-thirds majority and Lyon kept his seat.

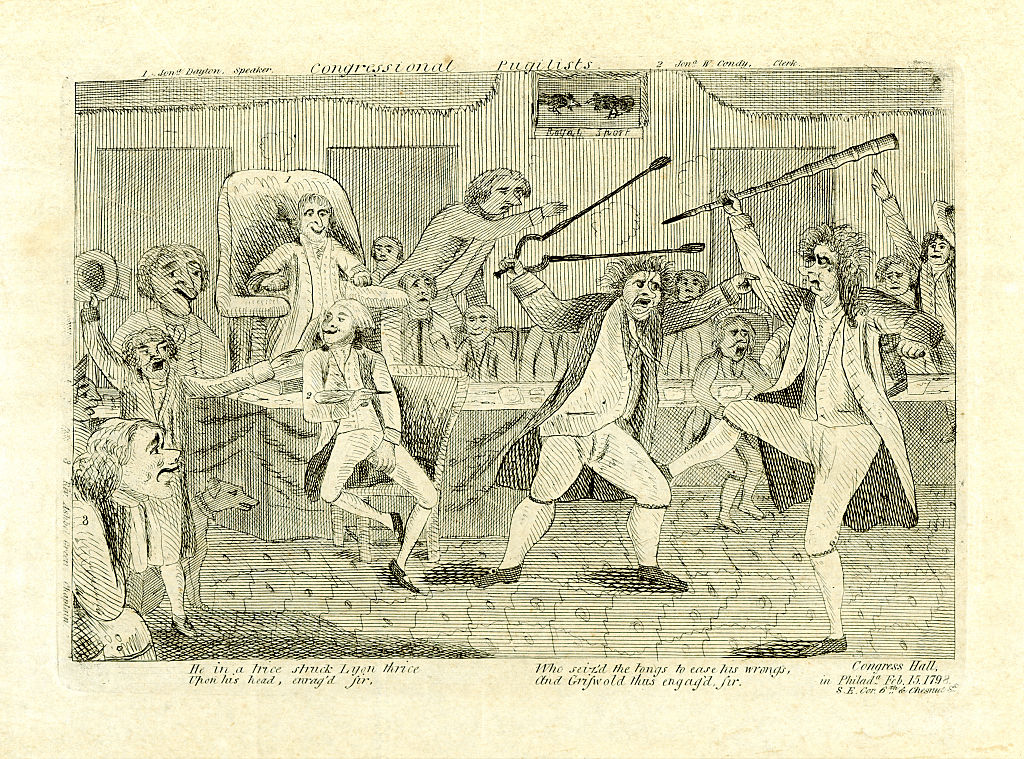

Shortly afterwards, Griswold took matters into his own hands. He attacked Lyon on the House floor, beating him with his walking stick. Lyon fought back with a pair of tongs he grabbed from a nearby fireplace. The two then wrestled to the floor, punching each other wildly until onlookers eventually broke them apart.

The fight further endeared Lyon to his supporters who claimed that his “honest, independent, and manly suppor[t]” of the “interests of the people” so angered “the aristocratic faction” that they had to resort to violence. The irreverent, rough-and-tumble nature of Lyon’s antics in Congress cemented his reputation as a common man fighting for the interests of his constituents against the establishment. And each time Lyon’s opponents criticized his conduct, they only strengthened those associations.

Later that year, Lyon was arrested for claiming that President John Adams was more interested in “ridiculous pomp, foolish adulation, or selfish avarice” than serving the public good. The federal court in Vermont convicted Lyon of violating the newly passed Sedition Law, which made it a crime to criticize the federal government.

His opponents hoped that this disgrace would ensure Lyon lost his re-election bid that fall. But, in fact, his arrest and conviction had the opposite effect, boosting Lyon's prospects. From jail, the congressman claimed martyrdom, penning plaintive accounts of his mistreatment and denouncing his opponents for imprisoning their political enemies. He maintained that the only crimes he had committed were “refusing to sacrifice [his constituents’] sacred trust to the views of those who wish to see a luxurious court.” And so, as before, the attempts of Lyon’s critics to delegitimize him only made the congressman more compelling to the voters.

Lyon won re-election, making him the first—and more than 200 years later, the only—person elected to Congress from jail.

His victory hit his opponents hard. They were in disbelief that the voters could have backed Lyon once again. “How lost to decency [are] the servile advocates of such an animal!” railed one commentator. The press denounced his supporters as “low-class,” “ill-mannered,” and disloyal. Nevertheless, once he had served his sentence, Lyon returned to the House of Representatives as a hero in the eyes of his followers.

Read More: How MAGA Hijacked the Conservative Movement

The tale of Matthew Lyon carries an important warning for those who wish to defeat Donald Trump. Calling out bad behavior is important and prosecuting illegal behavior even more so. But, as Lyon’s story demonstrates, ridiculing and mocking distasteful opponents and their supporters can backfire significantly. Lyon’s constituents saw these reactions as a sign that Lyon was fighting for them against a corrupt establishment. The opprobrium, venom, and scorn Lyon faced only enhanced his popularity.

Trump's critics on both the left and the “Never Trump” right have often resorted to similar expressions of outrage and demands for banishment. They, too, have mocked the MAGA movement and hurled insults at Trump voters. But Lyon’s example suggests that to defeat Trump, his opponents must work to understand his appeal.

Eighteenth-century Americans failed to tame Lyon. Whether 21st century Americans can crack the code of taming Trump remains to be seen.

Shira Lurie is assistant professor of History at Saint Mary’s University and author of The American Liberty Pole: Popular Politics and the Struggle for Democracy in the Early Republic. This article is drawn from her chapter in A Republic of Scoundrels: The Schemers, Intriguers, and Adventurers who Created a New American Nation.

Made by History takes readers beyond the headlines with articles written and edited by professional historians. Learn more about Made by History at TIME here. Opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of TIME editors.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Write to Shira Lurie / Made by History at madebyhistory@time.com