The Federal Reserve’s latest Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF) exposed a massive racial wealth gap in the U.S. In 2022, the typical African American family has 16 cents on the dollar compared to the typical white family—about $44,900 compared to $285,000. (The typical Hispanic family has 22 cents on the dollar compared to a median white family.) This perpetuates a pattern that dates to 1983, when Black and white workers’ wealth began to diverge across income brackets.

In the early 1980s, experts saw this gap as an anomaly and predicted that it would narrow as younger Black Americans with more education replaced older ones with less education in the work force. But these predictions proved false due largely to policy changes brought about by the sweeping Reagan Revolution, which remade policy and American politics in ways that exacerbated the racial wealth gap and made closing it difficult, even today.

The Reagan Revolution blew through government at a moment when the Federal Reserve’s campaign against skyrocketing inflation had begun dampening wages for workers, and finance was on its way to becoming king in the American economy. These changes meant fewer good paying jobs for African Americans and drove salaries up in professions dominated by whites.

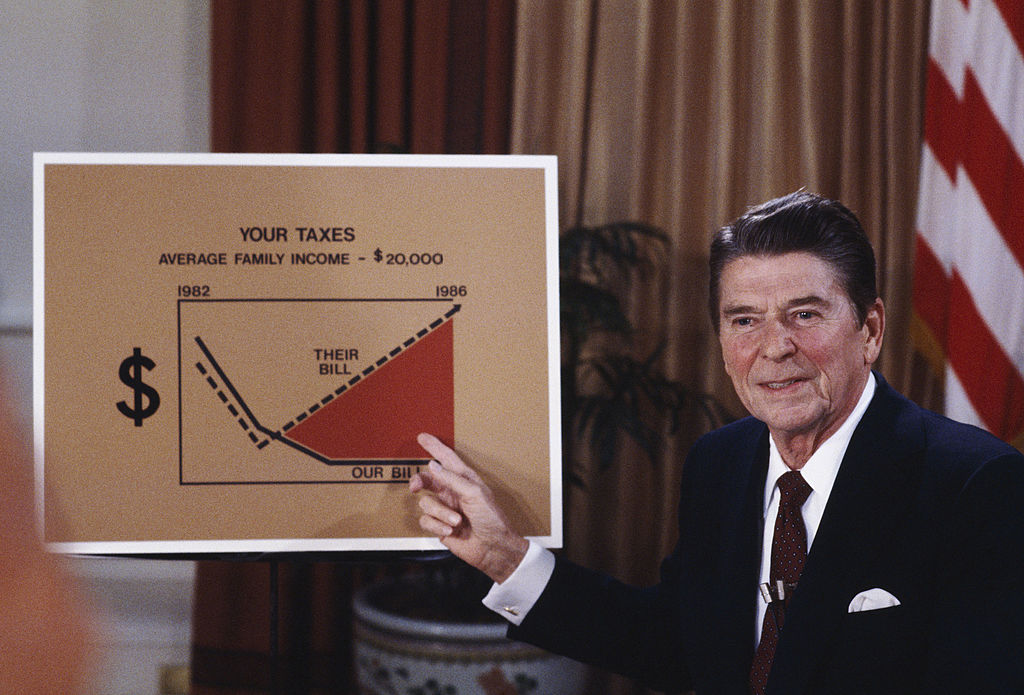

But the policies championed by Ronald Reagan exacerbated these trends. Reagan entered the presidency determined to slash taxes, deregulate markets, liberate capital, and decrease domestic spending. The crown jewel of his agenda was a sweeping, across-the-board income tax cut passed in 1981. Reagan and his allies embraced supply-side economics, predicting that cutting taxes on the wealthy would enable them to create jobs, thereby sharing prosperity with less prosperous Americans. These conservatives saw deficit-financed tax cuts as investments in the future, while dismissing spending on things like K-12 education and food programs as a waste of taxpayer money despite the fact that many of these programs paid for themselves.

But their economic theories proved disastrously false. Cutting taxes on top earners and capital gains, and financing it with deficits, ended up disproportionately benefiting white earners and owners of stocks. Those who earned wages and had high proportions of their family wealth tied up in homes, especially Black Americans, felt little of the wealth trickling down.

Reagan’s industrial policy also fueled the racial wealth gap because it pushed offshoring jobs and layoffs of U.S. workers. Across manufacturing industries, executive pay soared while companies sought cheaper labor overseas and U.S. plants closed. Meanwhile, the economy shifted to emphasize service work, which paid less and was far less likely to come with union protections.

Read More: Why Black Americans Need Black-Owned Banks

That was especially true because in 1981, despite being a former union president himself, Reagan fired 11,345 striking members of the Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization and refused to re-hire them. Busting a major union sent a message to employers that they could fire employees at will. That contributed to a decline in unionized workers across the board, which disproportionately affected African Americans who were over-represented in unions.

Even as offshoring and the decline of unions left Black Americans in the workforce vulnerable, Reagan gutted the apparatus designed to protect them. He appointed Clarence Thomas — a staunch opponent of affirmative action — as the director of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC). Under Thomas, the EEOC prosecuted narrow individual discrimination lawsuits rather than class action race discrimination claims, circumscribing its reach.

Making matters worse, just as this mix of policies led to a spike in Black unemployment, retraining for the new economy got more costly. Further, deregulation translated into speculation, loosened safety standards, and pricing shenanigans. When power shifted from workers to companies, Black workers lost. Very few African Americans sat on corporate boards or worked in company leadership.

President Reagan claimed that “Reaganomics . . . created opportunity for those who had before been economically disenfranchised: the poor and minorities.” But the opposite was true.

And it wasn’t just Reagan’s economic policies that fueled the racial wealth gap. The president was also a staunch champion of tough-on-crime policies. He presided during a time when the two political parties vied with each another for the title of toughest on crime in a bid for support from suburban white voters. Both parties backed laws like the 1986 Anti-Drug Abuse Act that fueled over-policing of Black and Hispanic neighborhoods, privatized law enforcement, contained racially disparate sentencing provisions, and fostered the private prison industry. The prison population doubled during Reagan’s presidency.

Mass incarceration disproportionately affected Black Americans. And a prison sentence could devastate a Black family economically, slashing its wealth by two-thirds. Fines, fees, lost income, and family debts crushed Black Americans after they had served prison sentences. Making matters worse, re-entering the workforce for Black men with a criminal record was exceedingly difficult compared to white men in the same position. Many who left the job market for jail never re-entered.

By the time Reagan left the White House, the trend toward widening racial wealth was unmistakable. By 1989, the typical white family had 17 times the wealth of the typical Black family. Scholars sounded the alarm, with sociologist Robert B. Hill concluding in 1989 that “structural” discrimination — the architecture of laws, markets, practices, and policies that governed economic life — was the key factor in obstructing Black advancement in the 1980s. Yet, these warnings failed to prevent policymakers in both parties from extending supply-side policies and accelerating mass incarceration.

No one better emblematized these trends than Bill Clinton, who became the first Democratic president in 12 years when he entered office in 1993.

His critics charged that Clinton “completed” Reagan’s social and economic program, growing the economy while widening inequality. He signed the North American Free Trade Agreement — which George H.W. Bush had negotiated — the centerpiece of trade policies that offshored manufacturing jobs. Clinton moved his party to the right economically, with the costs of his policies disproportionately harming African Americans, who had nowhere to go politically with the Republican party attracting white nationalists. Clinton’s 1994 Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act also led to higher rates of Black incarceration and an expansion of the school-to-prison pipeline by targeting juvenile offenders who were disproportionately Black and Hispanic. Finally, in 1996, after vetoing earlier versions, Clinton signed the Republican-authored Welfare Reform and Personal Responsibility Act, which exacerbated racialized social disadvantages.

This constellation of policies meant that under Clinton, whom Toni Morrison called “our first black president,” wealthy Americans got wealthier and the Black-White racial income gap widened considerably.

Clinton also supported several policies that laid the groundwork for the 2008 housing crisis, which cost Black households 48% of their wealth vs. only 26% for whites. These included the repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act, thereby allowing investment and commercial banks to merge. George W. Bush extended Clinton-era deregulation, and mortgage companies sold subprime loans to Black homeowners regardless of income. In 2008, everything came crashing down.

Running for president that year, Barack Obama criticized Clinton’s “winner‐take‐all, anything‐goes environment that helped foster devastating dislocations in our economy.” He embodied hope for a reversal in racial economic disparities. And President Obama did take steps ranging from the passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act in 2010 to stricter civil rights enforcement that addressed some of the roots of the wealth gap. He shifted drug policy emphasis from incarceration to treatment. But fundamentally, Obama never challenged the economic restructuring wrought by the Reagan Revolution. This meant that by the end of Obama’s second term in 2016, the Black-white wealth gap was greater than the wealth gap of the Reagan Era.

Donald Trump revived Reaganomics, cutting taxes on the wealthy and repealing Obama-era worker protections. His Justice Department tried reviving failed policies in the War on Drugs. These policies reinforced wealth inequality along racial lines, which was then exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

By the early 2020s, therefore, the wealthiest 400 Americans — mainly white tech and finance moguls — owned the equivalent of all 43 million Black Americans. African Americans’ life expectancy was also shorter, and health disparities compounded income and wealth disadvantages.

The history is clear: so-long as the basic architecture of Reagan’s economic vision — lower taxes on the wealthy, less regulation, less unionization — remains in place, closing the racial wealth gap will be hard. These policies have boosted the stock market and finance at the expense of manufacturing, lessened protections for workers, and increasing difficulty to enter the middle class. Democrats, including the Biden Administration, have tried to nibble around the edges in the three decades since Reagan left office, while Republicans, including the leading presidential candidates, want to double down on them. The truth, however, is neither set of prescriptions will address the racial wealth gap. For 40 years, the policies ushered in by Reaganomics have fueled its growth, and only a direct assault on this vision will begin to ameliorate the problem.

Calvin Schermerhorn is professor of history in Arizona State University’s School of Historical, Philosophical, and Religious Studies. His forthcoming book is The Plunder of Black America: How the Racial Wealth Gap was Made and Why It’s Growing. Made by History takes readers beyond the headlines with articles written and edited by professional historians. Learn more about Made by History at TIME here.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Calvin Schermerhorn / Made by History at madebyhistory@time.com