This article is part of The D.C. Brief, TIME’s politics newsletter. Sign up here to get stories like this sent to your inbox.

Few Presidents actually have an entirely good first year in the White House. Joe Biden presided over the fall of Kabul, the climb in COVID-19 cases thanks to the Delta variant, and the start of an inflationary climb that would see costs climb at the fastest rate in 40 years. Barack Obama faced Republican obstructionism at every turn, even as the 2008 housing crisis and ensuing recession was still raging. George W. Bush was selling a hard-fought and bipartisan education rewrite of the nation’s biggest education law when four airliners redirected American history on the morning of Sept. 11, 2001.

Yet Bill Clinton’s opening 12 months stands out for its blunders. It’s often used as a cautionary tale in courses as varied as leadership, history, civil rights, and business. “He's trying to please too many people all at the same time, without really looking at the heart of the issues,” one voter summarized at the time. His health care proposal drew immediate skepticism before a single word of it had been written in stone. Two Black Hawk helicopters’ crash in Mogadishu threw his domestic agenda off his game. In the press, he couldn’t catch a break; a tarmac haircut that delayed one other plane for two minutes became a lingering piece of Clinton’s selfish tendencies.

The unifying critique of the Clinton era is that he lacked a true core of character or discipline, that nothing he said ever could be counted upon when a better alternative—for him—became available.

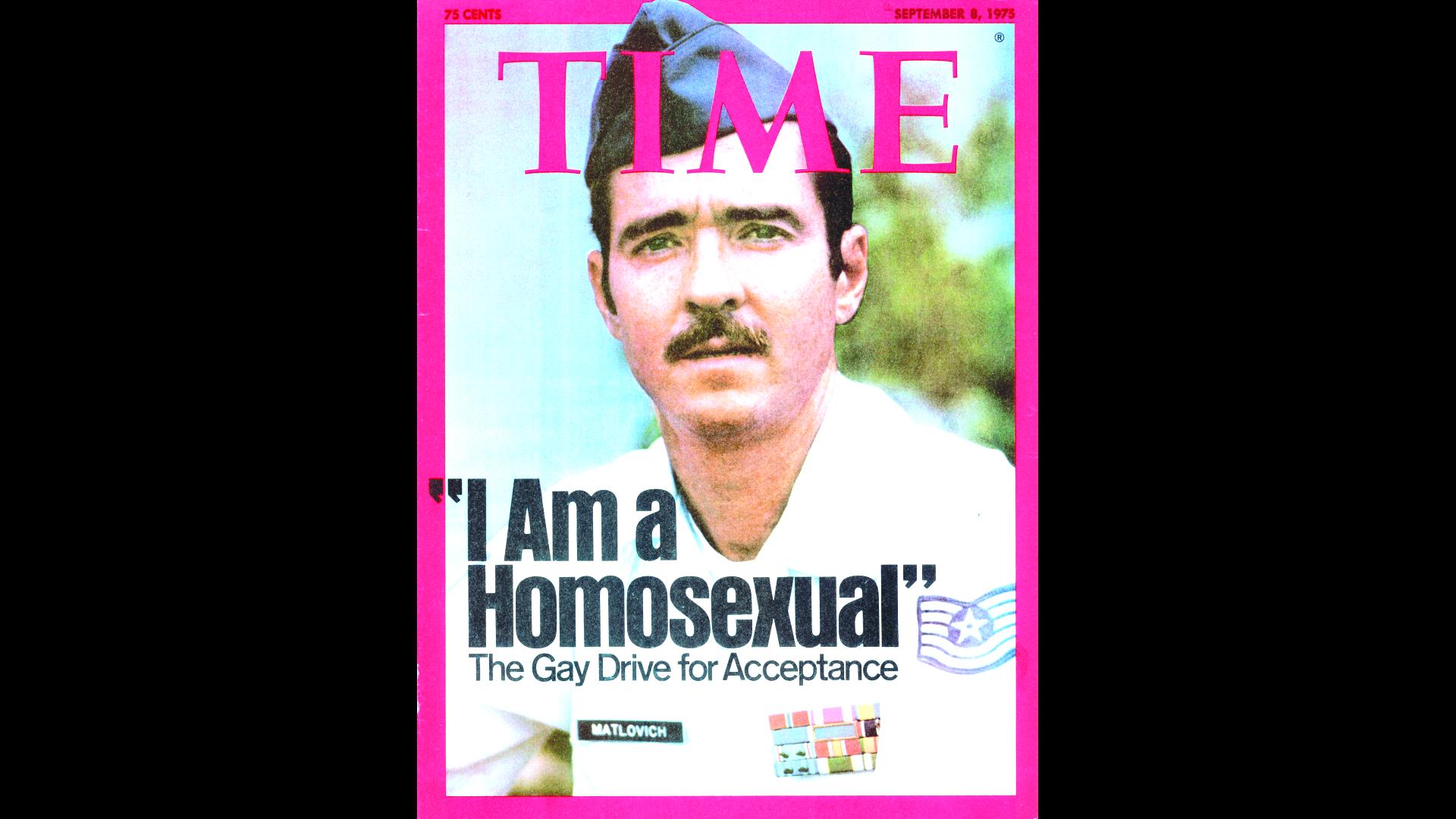

That tendency is an important chapter in a new documentary about the history of LGBTQ Americans’ military service. Serving in Secret: Love, Country, and Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell, co-produced by TIME Studios and airing Sunday on MSNBC, starts with the official ban on gay and lesbian service members during World War I, its escalation during World War II and the Cold War, and its draconian application that cost at least 14,000 Americans their military careers. But it’s Clinton’s clumsy handling that somehow comes across as the cruelest move to his friends and allies.

Bill Clinton assured LGBTQ and civil rights activists during his 1992 campaign that his election would mean a marked reversal of the previous 12 years, in which Presidents Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush were seen as responding to the still misunderstood HIV/ AIDS crisis with mockery and indifference. Using archival 1982 audio from the White House, the so-called “gay plague” drew chummy laughter as a spokesman met with reporters, who were hardly empathetic to a disease that was mostly hitting gay men in cities. (For a very fine history of Washington through the eyes of its gay community, there’s Secret City from James Kirchick.)

At the time, civil rights activist David Mixner took a phone call from a top Clinton adviser asking him to back the White House campaign. Mixner recalls that he considered Clinton a friend from their days protesting the Vietnam War and had helped raise money for Clinton’s earlier efforts. But he told the future Commerce Secretary on the line he had demands, among them a repeal of the ban on gays and lesbians serving.

“We don’t trust anybody any more, even the good guys,” Mixner recalls in an interview. Mickey Kantor passed along that Clinton would do it.

Mixner’s first instinct wasn’t wrong. While Clinton’s aides urged quick action on overturning the ban, the President more quickly learned how the federal bureaucracy can gum up the best-meaning plans. After a heated meeting with the military brass—now documented in real-time notes released from the National Archives—Clinton agreed to delay action.

Opponents of the measure mobilized—not just leaders in the Christian right but the powerful Democratic chairman of the Armed Services Committee. Clinton’s first press conference in the White House was dominated by questions about gays in the military and congressional opposition to their embrace. No one even asked Clinton about the economy, which had been the centerpiece of a campaign that had ended just weeks earlier.

“The issue immediately overwhelmed him,” says Jeh Johnson, who would lead the Obama-era review of LGBTQ policy as the Defense Department’s top lawyer. “He was dealing with very powerful political forces who were opposed to change.”

Clinton reasoned that a law would be durable, while an executive order would be at the discretion of Presidents who followed him. But he didn’t count on how much harder it would be to convince Congress to see things his way.

“Political leadership in both parties was very opposed to this,” says Eric Fanning, a former White House political aide during that era, who would later become the first openly gay service chief as Secretary of the Army under Obama “The effect was forcing public discussion of this before the Clinton administration was organized. So it got everyone off to a bad footing from the jump.”

Activists, including Mixner, had little patience. He helped lead a protest in Washington, ending with his arrest on Pennsylvania Avenue and a terse phone call from Clinton himself who didn’t much care for a well-known Friend of Bill breaking so publicly with the White House. (The pair reconciled a few years later.)

But the dominos had been laid to fall. The public was inundated with a subject most knew little about. Some lawmakers—including those today considered allies—deployed some horrid language and stereotype. “My gut reaction is that they (homosexuals) are security risks,” Biden said during his first few months in the Senate.

Tom Carpenter, a Naval Academy graduate who resigned his Marine commission when his lover was wrongly accused of sexual assault and discharged without honor, emerges as one of the most driven characters in the film. His post-uniform career involved helping shape the external response to the Clinton-era Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell law, Service members were supposedly allowed to keep their positions as long as they kept their sexuality a secret in exchange for the end of higher-ups probing into their colleagues’ personal lives. “We backed ourselves into a law,” Carpenter says in the film. It never really worked and was never uniformly applied, as the documentary suggests, such as for Arabic translators after the 2001 terror attacks. (There were, on the other hand, plenty of stories of Arabic translators ending their service when discovered.)

The end of DADT was predictably messy and the film, in fast succession, explains how the politics of the moment demanded urgent repeal of it before Democrats lost power after the 2010 election. But for those 17 years, the military essentially demanded its membership from top to bottom to conceal a piece of themselves. It was certainly a byproduct of its era—President Barack Obama, who signed its repeal, was hardly a purist on LGBTQ rights during his career—and it definitely reflected another President who was watching his entire ambitious agenda for Washington and the world be consumed by a fight over this topic. Yet the Clinton-era DADT stands as a case study for any number of reasons, not the least of which is the limits of campaign promises and the pitfalls of translating those promises into concrete agendas. It also provides lessons for those working to pressure the Biden administration on everything from student loan forgiveness to a ceasefire in Gaza. As much as Serving in Secret is about the fight for one piece of LGBTQ history, it’s a broader work that cuts at how Washington really works, and it’s not always as easy to find heroes as most would think.

Make sense of what matters in Washington. Sign up for the D.C. Brief newsletter.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Philip Elliott at philip.elliott@time.com