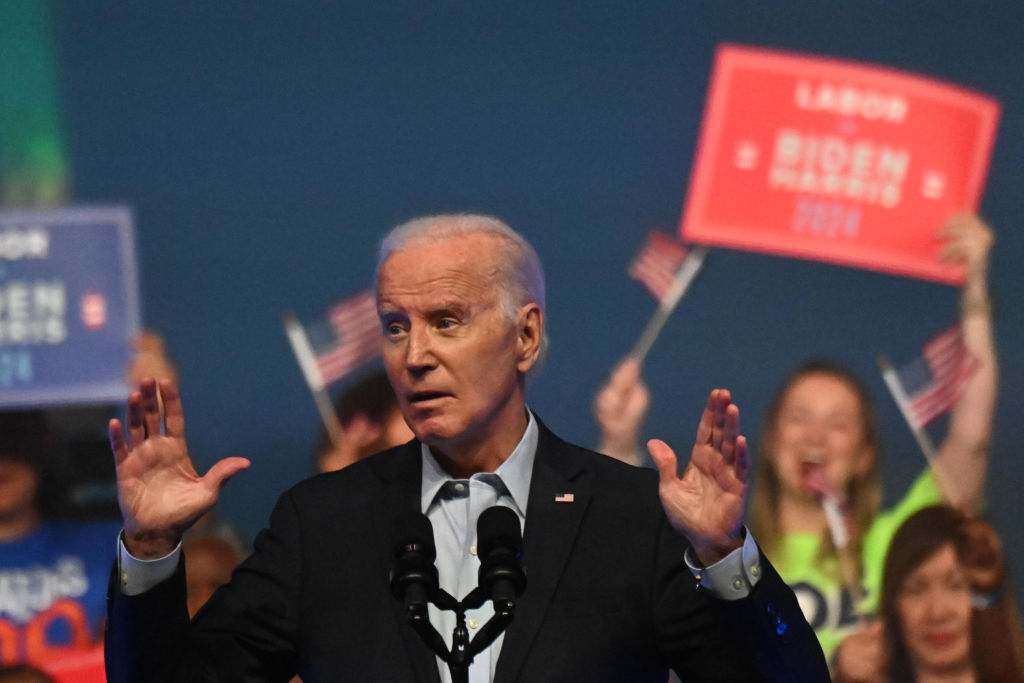

As the incumbent president, Joseph R. Biden Jr. is the presumed Democratic nominee for the 2024 election. He even won Tuesday’s New Hampshire primary without being on the ballot or campaigning. And yet he faces low approval ratings, concerns about his age, and clamoring among his own party about the need to step aside to ensure that Donald Trump does not capitalize on Biden’s weakness to return to the White House.

Were President Biden to drop out, the decision would have only two precedents in modern U.S. history: Harry Truman in 1952 and Lyndon Johnson in 1968. Then, these two moderate Democrats, who each at one point looked like a shoo-in for reelection, suddenly decided to drop out of the race.

First, Truman. With his public approval rating hovering around 23%, on Nov. 5, 1951, about a year before the election, Harry Truman tried to feel out his presumed Republican rival, General Dwight Eisenhower. He asked him directly about his political future, promising, “It will be between us.” Eisenhower’s response was a little disingenuous given later events. “You know, far better than I, that the possibility that I will ever be drawn into political activity is so remote as to be negligible,” Eisenhower wrote on Jan. 1, 1952.

Read More: Biden’s Message to Americans Who Don’t Want Him to Run Again: ‘Watch Me’

Truman could not help but feel misled when Eisenhower’s campaign manager, Senator Henry Cabot Lodge Jr., announced his candidacy in the New Hampshire Republican primary five days later. Eisenhower won the New Hampshire primary on March 11 by more than 10,000 votes against the Republican Party’s more conservative candidate, Robert Taft. As a result, once Truman saw that his chance of winning reelection was seriously in jeopardy, he announced he would not seek reelection on March 29—waiting as long as he could so fewer people would interpret the decision as a response to Eisenhower’s surge.

Truman’s announcement at an important fundraising dinner caught his party by surprise and threw the race wide open on the Democratic side of the aisle. Illinois Governor Adlai Stevenson, who would become the party’s nominee in both 1952 and 1956, was seen as having the most to gain. Truman ultimately appeared at the convention in Chicago, endorsed Stevenson’s nomination, and assisted his party’s lurch to the left during the remainder of the decade. The Democrats lost decisively at the top of the ticket until shifting back to the center in 1960 with Senator John F. Kennedy as their nominee.

A similar, if not more dramatic, situation emerged with Lyndon Johnson, who announced on national television on March 31, 1968, that he would not run for reelection. Initially, many commentators considered it a rash decision, perhaps in response to the Tet Offensive (which undermined LBJ’s claims that the U.S. would win the ongoing war in Vietnam) or his poor showing in the New Hampshire Democratic primary (against a little-known antiwar candidate, Senator Eugene McCarthy). However, newly available records demonstrate he began considering his political future much earlier. Lady Bird Johnson wrote in her diary on March 31 that she had heard him say for months, "'I do not believe I can unite this country,'" and noted "most of the complaining is coming from Democrats."

Johnson’s health played a bigger role than people realized at the time. “Two hospitalizations for surgery while I was in the White House had sharpened my apprehensions about my health,” he wrote in his memoirs. Johnson had a family history of stroke and heart disease. His own father had died at age 60, the age LBJ would reach in 1968. Johnson also understood how the presidency had drained the vitality of Democratic heroes Woodrow Wilson and Franklin D. Roosevelt before their terms ended. Anyone could see how much Johnson had aged in office. Did he really have it in him to run a vigorous campaign against a more energetic rival?

Even worse for Johnson, Sen. Robert Kennedy—younger brother of the late President Kennedy, and an old nemesis of LBJ’s from their days together in the Kennedy Administration—had recently entered the race. With his youth, popular antiwar stance, strong name identification, and strong financial position, Kennedy looked to have a good chance of unseating the increasingly unpopular Johnson. When Kennedy joined the Democratic primary race on March 16, 1968, about two weeks before LBJ ultimately dropped out, he expanded upon Sen. McCarthy’s criticism of Vietnam by saying he also was running because of Johnson’s poor handling of domestic policy—generally viewed as LBJ’s stronger suit. “With America’s sons in the fields far away, with America’s future under challenge right here at home, with our hopes and the world’s hopes for peace in the balance every day, I do not believe that I should devote an hour or a day of my time to any personal partisan causes or to any duties other than the awesome duties of this office—the Presidency of your country,” Johnson said, withdrawing from the race.

Read More: The Election Where a Democratic President Secretly Wanted the Republican to Win

Johnson waited as long as he could to make the announcement, fearful that he would instantly be a lame duck. He had planned to make it as early as his final State of the Union in January. However, Johnson, aware that Truman made his decision on March 29, wanted to wait closer to then to be consistent with precedent.

Such a delay had consequences for the Democratic Party though. It was too late for other challengers to mount a primary campaign. Key campaign staffers had already committed to other candidates. Delegates loyal to others were already headed to the convention in Chicago. Needed fundraising efforts positioned Democratic hopefuls well behind the growing Nixon war chest on the other side of the aisle.

So what will Biden do?

The lesson of history is that if he becomes convinced his reelection is in serious jeopardy, it would be better for him to make up some reason to step aside rather than go down to defeat. With Tuesday’s victory, there isn’t an obvious point in the primary process that would signal to Biden that his reelection is truly imperiled. Yet, if he’s trailing Trump, the presumptive Republican nominee, by summer, he’ll face increased pressure to step aside before its too late. It would be in his personal interest to decide as late as possible, like Truman and Johnson, as such an announcement could put him in a difficult position to salvage his remaining agenda. Whenever he might withdraw from the race, he would receive a surge of goodwill for seeming to put his party (and the nation) first, but he would also be labeled a lame duck and would endure staff defections to challengers.

But, the later the decision the worse it would be for his party since serious alternatives would have less time to organize. In that case, the convention could truly be an open, competitive one rather than the rubber stamp it usually is.

Read More: The 2024 Presidential Election? Democrats Have Already Won

Whether Biden runs or not, his attention will soon focus on his legacy. He will certainly want to influence the choice of his successor. In that case, we need to look beyond party labels and political commitments. It is said that politics makes strange bedfellows; history shows that this is especially true when it comes to the crafting of political legacies.

We often forget that an awful lot happens in Washington for personal, selfish reasons. Both Truman and Johnson were inclined to support those closer to their own image—regardless of political party. Biden will surely play the cards close to the vest and do this very privately, which could actually deal an advantage to a moderate. As with Truman and Johnson, it could be decades until we have a fuller understanding.

Luke A. Nichter is a Professor of History and James H. Cavanaugh Endowed Chair in Presidential Studies at Chapman University in Orange, Calif. He is the New York Times bestselling author of eight books including, most recently, The Year That Broke Politics: Collusion and Chaos in the Presidential Election of 1968 (Yale University Press, 2023). He is now at work on a volume tentatively titled LBJ: The White House Years of Lyndon Johnson. Made by History takes readers beyond the headlines with articles written and edited by professional historians. Learn more about Made by History at TIME here.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Luke A. Nichter / Made by History at madebyhistory@time.com