After Billy Graham, the famous preacher and presidential confidante, passed away in 2018, Luke Nichter was one of the first researchers to get a glimpse at previously unseen Graham diary entries kept at the evangelical Wheaton College.

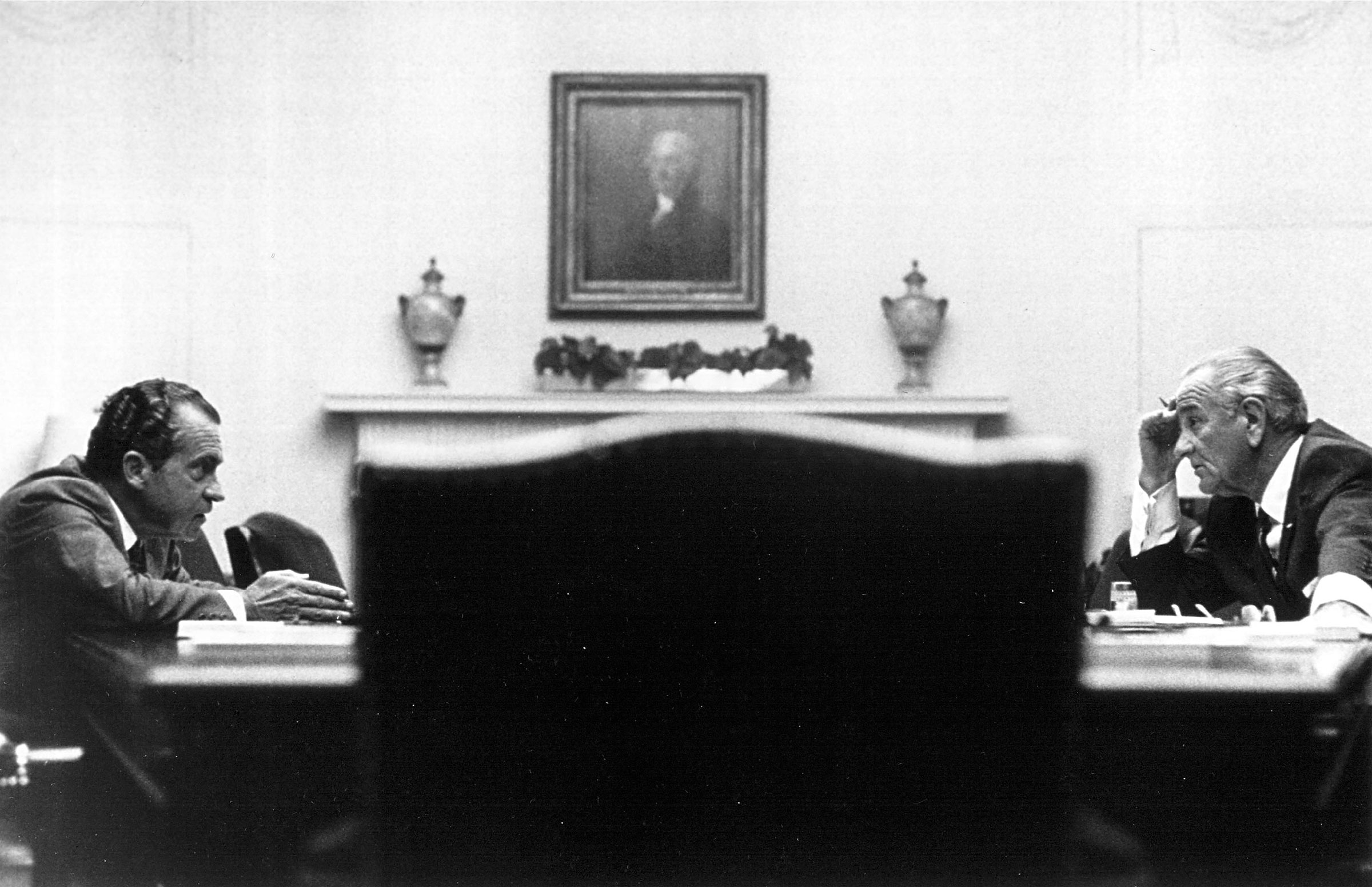

Nichter’s new book The Year That Broke Politics: Collusion and Chaos in the Presidential Election of 1968, out today, is the first to be based on Graham’s personal diaries. The entries reveal that incumbent Democratic President Lyndon B. Johnson worked behind the scenes that year to help get Republican Richard Nixon elected.

In a phone conversation on July 17, Nichter explained how the Democratic Party became so divided, why Johnson wanted Nixon elected, and how the politics in the 1968 presidential race are similar to the upcoming 2024 presidential election.

The following conversation has been lightly edited.

What’s the most surprising thing you learned in your research?

This is the first book to make the argument that, in fact, Johnson probably preferred the Republican presidential nominee Richard Nixon, his longtime nemesis and political rival, to win the 1968 presidential election. I was writing this book based on access to the Graham diary that nobody else had. It’s clear through the diary that Johnson says that he believes Nixon is the most qualified to be President of those running and he believes he will be President—and this is right after the funeral of 1968 presidential candidate Bobby Kennedy. I thought, wow. Then I had that confirmed by Johnson people, and in a meeting I had with Vice President Walter Mondale, he emphatically said, Lyndon Johnson definitely did not want Hubert Humphrey to win. And Mondale was very close to Humphrey—he co-chaired his 1968 presidential campaign. It was really Mondale who challenged me to go down this rabbit hole that I was not planning to go down.

Why did LBJ want Nixon to be elected President over his own Vice President Hubert Humphrey?

Nixon was not criticizing Johnson on the Vietnam War, and was saying, for Republicans, surprisingly liberal things, shaded in a more conservative way. Instead of talking about big spending on welfare programs, Nixon would talk about private investment in cities, Black businesses, and mortgage assistance. He wasn't suggesting that he would overturn any of the centerpieces of Johnson's Great Society. I don't think Johnson voted for Nixon. I don't say he preferred or he supported Nixon. I'd say he came to believe that Nixon was preferable for his own legacy. That's what was foremost in Johnson's mind, his own legacy. Nixon says a number of times to his campaign aides, ‘Don't criticize Johnson. I know it's awkward, but he's not criticizing us.’

So Johnson, by 1968, had grown apart from the more liberal Democrats in his party. Is that over the Vietnam War or a different political issue?

It was mostly Vietnam, but it was more than Vietnam. After all the riots that had happened in over 100 major US cities starting in 1965—especially 1968, after Martin Luther King Jr.'s assassination—Johnson had the Kerner Commission study the reasons behind rising crime and race and these riots. Some in his own party were also thinking that Johnson hadn't done enough on those issues. There were Democrats who wanted Johnson to go much further in his Great Society programs that he was willing to.

By ‘66, Vietnam had become a political liability for Johnson, with more and more members in his own political party, such as Eugene McCarthy, calling not just for an end to the war, but a different strategy and ultimately, even a withdrawal.

What were the core campaign issues driving voters to the polls back in 1968?

It started out being about the war. Two assassinations really changed the whole tenor of the campaign—Martin Luther King, Jr. in April and Senator Bobby Kennedy in June. And that really shifts the campaign focus to domestic issues: Tension, unrest, riots, racial crime, police violence—a number of themes that resonate with us today.

In your book, you mentioned that Nixon's political career appeared to be over after his failed presidential candidacy in 1960 and an unsuccessful run for California governor in 1962. You even cite a TIME magazine article that reported that his political career had ended “barring a miracle.” How did Nixon go on to win the 1968 presidential election?

Billy Graham's diary again is key. Graham shows that he went down to Key Biscayne, Florida, where Nixon was staying around New Years ‘67-’68, and his diary suggests he convinced him that he thought it was Nixon’s destiny to run, that he deserved another chance that had been taken away from him. Graham had tipped Nixon off that Johnson was not going to run.

And so Graham is kind of maneuvering around the circle of characters to make sure that Nixon can get nominated and also he's encouraging Julie Nixon and David Eisenhower in their dating relationship. He believes bringing the Eisenhower and Nixon families together is better for Nixon's political career, and the couple gets married later that year in [December] 1968. So Graham is just systematically ensuring that Republicans would get behind Nixon. And then convincing Nixon that he needed Johnson, that Johnson needed Nixon, was the next phase of that. It was a systematic approach, and I don't know of anything else like it in U.S. history.

Your book talks about how former President Donald Trump and 1968 Republican presidential candidate George Wallace were similar. When did Wallace sound most like Trump?

Both of them focus so much on the white working class. I don't think either one put those fears in those particular voters. They put a spotlight on [those fears], and they use them to agitate and bring [the candidates] to prominence. Wallace clearly did that, speaking to concerns about Great Society. A lot of white working class people thought it was their kids who are being killed in Vietnam. Their neighborhoods were being taxed. Their paychecks were being eaten up by inflation. And Wallace would just get on a roll with these points. Sounds like a Trump rally.

What parallels do you see between the 1968 presidential election and the upcoming 2024 presidential election?

The 1968 presidential election has a lot of similarities to 2024: an incumbent deeply unpopular, especially in his own party. The opposition party seeking to nominate the first person who has a reasonable chance. This country is divided. We're not sure where we're going in terms of international affairs. There's not really a clear consensus on a lot of issues. The thing about ‘68 that most resonates with our own time period is a lot of voter apathy. If you look at ‘68 and now, a lot of Democrats aren't happy with their nominee or their supposed nominee. A lot of Republicans aren't happy with their nominee. A lot of people are going to stay at home and not vote. And I think the election was, in ‘68, largely decided not by someone that people loved, but the least bad of the alternatives, which, for voters today, is a theme they're familiar with.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com