Since the Hamas terrorist attacks on Oct. 7 that have now killed around 1,400 Israelis, a fierce debate has been raging in the United States. An outspoken minority on the left has portrayed the attack as an inevitable response to oppression. But the majority viewpoint among Democrats and Republicans alike has been revulsion against Hamas and support for Israel’s right to self-defense.

The majority position fits with Americans’ longstanding views on terrorism, which has been informed by a strong desire for “moral clarity” in every situation. Terrorism is 100% wrong in every situation and stems not from complex historical contexts and legitimate grievances, but from hatred and radical ideologies.

But while condemning terrorism should be a no-brainer, moral clarity has not guaranteed sound U.S. counterterrorism policies over the last half-century. This history shows that moral absolutism can obscure the compromises required to fight terrorism. It also encourages a self-righteousness that inhibits understanding of terrorism’s complex roots—which is necessary to best prevent it.

The modern U.S. struggle with terrorism began in the 1970s and 1980s, as nationalists like the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), extreme leftists like the German Red Army Faction, and state sponsors like Libya targeted the U.S. and its allies.

Read more: How the Activist Left Turned On Israel

The concept of "moral clarity" emerged in the 1980s as the Reagan Administration made terrorism a priority, believing that Jimmy Carter had focused too much on human rights and not enough on foreign threats. Advocates of moral clarity sought to discredit arguments that terrorism stemmed primarily from the legitimate grievances of dispossessed peoples suffering under racist and imperialist regimes—many of which were U.S. allies. Moral clarity enabled them to explain terrorism’s roots in a way that exempted the U.S. from any responsibility and cleared the path for a forceful response.

For example, in 1984 Secretary of State George Shultz criticized the idea that U.S. policies, such as support for Israel, were the root cause of terrorism. He described this view as “moral confusion” and argued: “We have been told that terrorism is in some measure our own fault, and we deserved to be bombed.” But Shultz dismissed such thinking. Terrorists were would-be totalitarians whose radical ideologies drove them toward absolute goals like the destruction of Israel. Caving to them on particular issues or changing American policy wouldn’t end their violence. It would only fuel it. Terrorists struck the U.S., Shultz claimed, “not because of some mistake we are making but because of who we are and what we believe in.”

Read more: What the World Can Learn From the History of Hamas

Moral clarity resonated with U.S. policymakers in this period for practical as well as ethical reasons. Many post-colonial states at the United Nations, such as Algeria and Tanzania, tried to exempt “national liberation” movements like the PLO from the label of terrorism despite their repeated attacks on civilians. Furthermore, some U.S. allies attempted to reduce the risk of terrorism by releasing suspects or refusing to extradite them. American policymakers hoped that by drawing stark moral lines, they could harden international resolve and isolate terrorist groups and their sponsors.

In 1990s, the intensifying culture wars roiling American society increased conservatives’ reliance on moral clarity as a principle, including against terrorism. While the culture wars largely affected domestic policy, conservatives saw a foreign policy connection. Restoring moral absolutes was the only way to repair what they viewed as a relativistic and decadent society—one that lacked the self-confidence needed to counter foreign threats.

Conservatives only became more certain of the need for moral absolutes after 9/11. The prolific culture warrior and former Secretary of Education William J. Bennett founded “Americans for Victory against Terrorism” to counter leftist anti-war sentiment on college campuses. He described 9/11 as “a moment of moral clarity…when we began to rediscover ourselves as one people even as we began to gird for battle.” Total certainty in America’s virtue was necessary to unite the country around an expansive war against terrorism and the renewal of order and tradition at home.

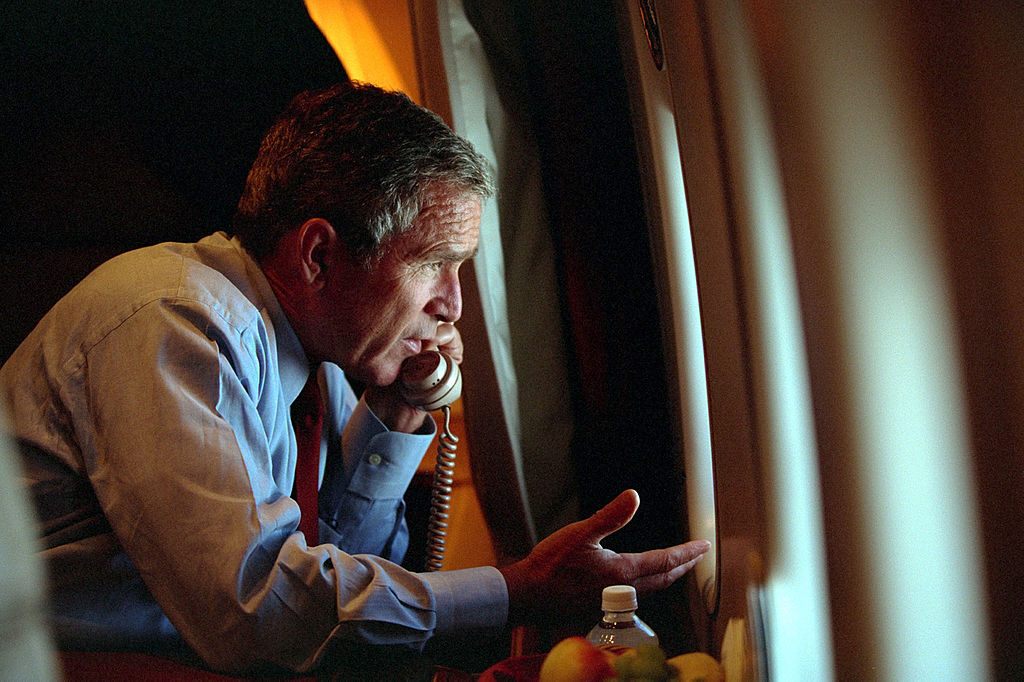

President George W. Bush echoed these principles, asserting that “Moral truth is the same in every culture, in every time, and in every place.” Bush declared of Islamist extremists: “They hate our freedoms-our freedom of religion, our freedom of speech, our freedom to vote and assemble and disagree.”

Moral clarity, however, didn’t produce good policy decisions in the War on Terror. It encouraged Bush and his team to assume that the universality of liberal democracy would enable the transformation of internally riven societies that had never been democratic. These dreams collapsed in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Moral clarity also inhibited Bush from thinking through the difficult ethical trade-offs of counterterrorism policy. Even as he championed democracy as a means of moderating the anger that drove many to extremism, his administration worked with and even bolstered autocratic partners like Russia, Pakistan, Egypt, and Saudi Arabia to combat Al Qaeda. To facilitate operations in Afghanistan, for example, the Bush administration expanded its support of Islam Karimov’s regime in Uzbekistan. This dictatorship jailed and tortured opponents, helping radicalize Uzbek Islamists.

Because the U.S. was demanding cooperation against Al-Qaeda, Bush was in no position to push dictators to risk their own survival by instituting real reforms. Moral clarity proved elusive where the U.S. needed help from autocratic partners, even as those autocracies exacerbated the problem of extremism in the long run.

Finally, moral clarity prevented Bush from digging into the role American policy may have played in creating the grievances driving Al Qaeda. It is impossible to explain the rise of the terrorist group without reference to U.S. policies like its partnership with the Saudi government or its stationing of troops in the Persian Gulf in the 1990s. While none of these factors provided justification for the heinous attacks on 9/11, reevaluating U.S. policy could have helped forestall further extremism.

While Bush’s failures in Iraq and Afghanistan made a new breed of Republicans increasingly open to an America First, anti-interventionist foreign policy, they did not destroy the belief on both sides of the aisle that terrorism demanded moral clarity.

That has been clear since Oct. 7. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and others have praised President Biden for “the moral clarity that you have demonstrated from the moment Israel was attacked.” Secretary of State Tony Blinken stated, “This is—this must be—a moment for moral clarity. The failure to unambiguously condemn terrorism puts at risk not only people in Israel, but people everywhere.”

Biden and Blinken are right that moral clarity provides a useful counterweight to those who have excused Hamas’ actions. It affirms that no cause, ideology, or set of real or imagined grievances can justify the deliberate slaughter of civilians. It also refutes the canard that “one man’s terrorist is another’s freedom fighter.” Hamas, like most terrorist groups, is not fighting for freedom or democracy, but only to solidify its power and impose its radical ideology.

Yet, as the War on Terror demonstrated, moral clarity has significant limitations and drawbacks. It can lead policymakers astray while failing to prepare them for the necessary trade offs that fighting terrorism requires. Moral clarity is also not a useful lens for understanding the roots of the extremism fueling terrorism, which is a necessary step for finding long-term solutions.

Learning this history can improve our response to the current situation. Denouncing terrorism unambiguously, as Biden has done, is a must. But the U.S. is now backing a far-right Netanyahu government that is eroding the rule of law in Israel, bolstering extremist groups, and making a resolution to the conflict unfeasible by supporting settlements in the West Bank.

Once this crisis recedes, the U.S. should not let its rightful condemnation of Hamas prevent reconsideration of whether it needs to push Israel to take more steps—like ending the blockade of Gaza or stopping new settlements in the West Bank—that might produce peace by addressing Palestinian grievances.

Halting settlements will not lessen Hamas’ determination to destroy Israel. However, it may intensify many Palestinians’ growing disillusionment with Hamas by undermining its false claim to legitimacy as a resistance organization. If the U.S. cannot convince Israel to change course, this conflict will continue.

It’s true that terrorists, including Hamas, are radicals undertaking evil actions. Moreover, the horror of terrorism understandably prompts humane people to demand moral clarity. Yet, by explaining terrorism exclusively in these terms, moral clarity can hamper our capacity to address the problem. It can also feed a self-righteousness that, in the War on Terror, led to overreaction and self-inflicted blunders. Accepting the inevitability of some moral murkiness, therefore, is an unpleasant but important step.

Joseph Stieb is a historian and an assistant professor of national security affairs at the U.S. Naval War College. Made by History takes readers beyond the headlines with articles written and edited by professional historians. Learn more about Made by History at TIME here.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Joseph Stieb / Made by History at madebyhistory@time.com