This Oct. 16 marks the 100th anniversary of the Walt Disney Company. With over 200,000 employees and a market capitalization exceeding $150 billion, it is one of most successful and influential media conglomerates in the world. But that good fortune was not a foregone conclusion. Indeed, 40 years ago, Disney almost fell apart. It would be easy to credit its survival to savvy business executives, including the company’s legendary namesake. But its longevity is due in no small part to its storytellers: animators, actors, writers, songwriters, directors, and producers, among them.

In its early years, Walt Disney Productions (its name from 1929 to 1986) was an independent producer. Its animated shorts and, later, feature films were released via distribution deals with larger Hollywood studios, including Columbia, United Artists, and RKO Pictures.

Then, in 1953, Disney founded its own distribution company, Buena Vista. Rather than depending on other studios, Disney could now handle the release of its own productions. The following year, Walt Disney began hosting a television series on ABC entitled Disneyland to help fund and promote a brand new theme park in Anaheim of the same name, which would open to the public in 1955. With its “total merchandising” strategy, Walt Disney Productions solidified its position in Hollywood by becoming a diversified media company with a range of investments and interests that could be effectively cross-promoted.

More From TIME

Read More: The Writer Who Helped Disney Heroines Find Their Inner Feminist

But after Walt Disney died in 1966, the company languished without a strong creative leader. Its animated film The Jungle Book did well, but throughout the 1970s, critical and commercial reception to films like Pete’s Dragon (1977) and The Fox and the Hound (1981) were mixed and often underwhelming. As a result, the studio’s film production slowed down. Executives’ attention shifted to the company’s more reliably profitable theme parks, now including Walt Disney World, which opened in Florida in 1971. Meanwhile, the company publicly admitted that it was wrestling with the viability of its safe, family-friendly image amid the rising popularity of more teen-oriented blockbuster spectacles from George Lucas and Steven Spielberg. Although Disney initially turned down the chance to produce Star Wars (1977), it eventually pivoted in 1979 to making its own, though far-less-impressive, space-age fantasy film, The Black Hole.

Marked by creative failures and financial setbacks, the 1970s and early 1980s period has been considered the studio’s “Dark Ages.” Concerted efforts to reach young adult audiences faltered time and again. The ending of The Watcher in the Woods (1980) was reshot following a disastrous reception in limited release. Tex (1982), Tron (1982), and Something Wicked This Way Comes (1983) disappointed at the box office.

But outside of the film division, there were noteworthy triumphs. In 1982, the company opened another park in Florida: EPCOT. Tokyo Disneyland, which Disney decided to license rather than manage itself, was another considerable success for the company and its business partners in 1983. The same year, Disney launched The Disney Channel as a subscription-based cable TV channel, while in early 1984, the company founded Touchstone Films to produce adult-oriented entertainment distinct from Walt Disney Productions’ family-friendly brand.

Disney may have struggled at the box office, but for Wall Street, it still had two valuable assets: popular theme parks and a formidable film library. Businessman Saul P. Steinberg seized the opportunity to attempt a hostile takeover. Executives resisted his efforts by burdening the company with debt and then buying back Steinberg’s stocks at a premium. The board’s trust in executives’ decision-making, however, suffered as a result. They ousted the executives, including Walt’s son-in-law and company president, Ron. W. Miller, in favor of Michael Eisner and Frank Wells.

As the new CEO, Eisner began to promote the idea of a Disney Renaissance. With Jeffrey Katzenberg, Eisner began working to deliver on that promise by refocusing on live-action filmmaking and television production. The new Disney regime found its earliest successes in comedies and dramas for adults. In film, they offered audiences Splash (1984), Down and Out in Beverly Hills (1986), The Color of Money (1986), and Ruthless People (1986), and on television, The Golden Girls (1985-1992). These projects succeeded in no small part because of the power of established and emerging stars, including Tom Hanks, Paul Newman, Tom Cruise, Bette Midler, Bea Arthur, and Betty White.

But Eisner and Katzenberg were less excited about the role that animated feature films would play in a corporate renaissance because they were costly and time-intensive to make, and the audience reaction was unpredictable. They kept this division of the company alive largely at the insistence of Walt’s nephew, Roy E. Disney. A tentative move into home video, however, provided a surprising boost to the bottom line for this aspect of Disney’s business. Rereleasing the animated features directly to consumers in the retail market, instead of theatrically, offered a crucial, new revenue stream.

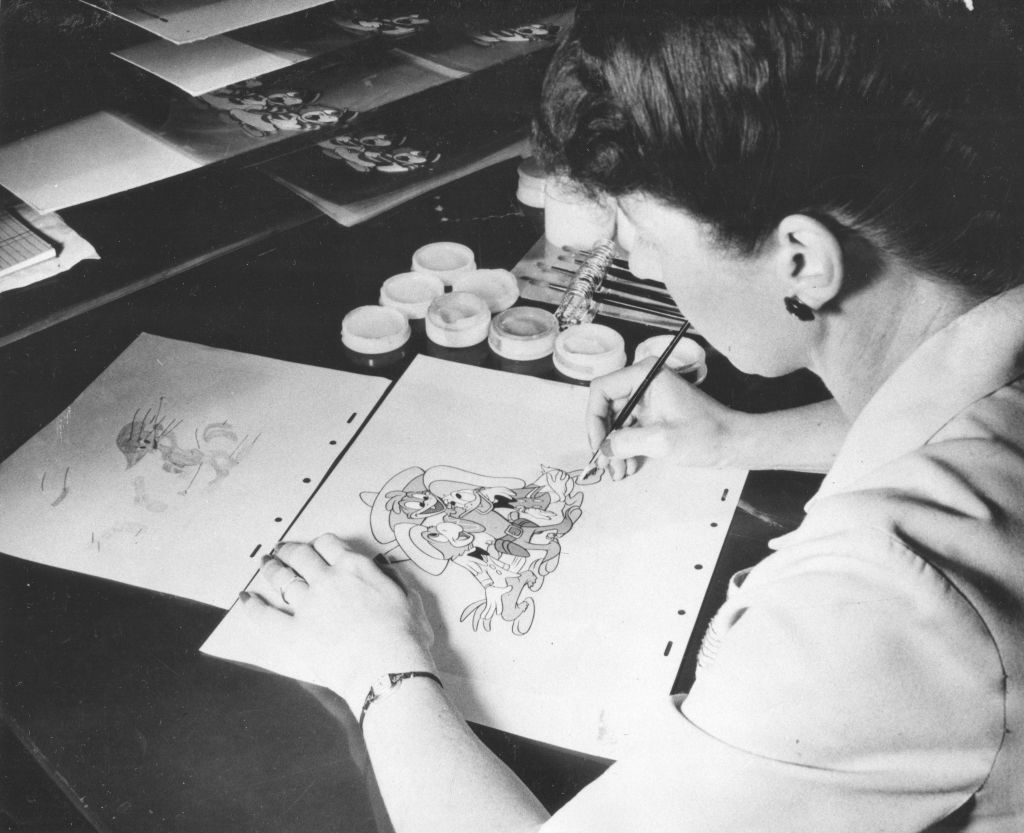

Throughout the 1980s, Disney animation was slowly showing signs of new life. The use of computer-generated imagery in Tron (1982), The Black Cauldron (1985), and The Great Mouse Detective (1986), and the action-adventure hijinks in Oliver & Company (1988) and Who Framed Roger Rabbit? (1988), indicated a renewed creativity in feature animation. Talent from the theater world, including Howard Ashman and Alan Menken, introduced theatrical approaches to musical storytelling, first in The Little Mermaid (1989), then to even greater effect in Beauty and the Beast (1991), the first animated film nominated for the Academy Award for Best Picture.

Aladdin (1992), The Lion King (1994), and Pocahontas (1995) continued to synthesize theater-making and animation to critical and commercial success. This run of animated films was particularly important for two reasons. First, they shifted executives’ focus away from live-action filmmaking to feature animation. And, second, they reinvigorated Walt Disney’s original formula, putting feature animation at the center of the company’s operations and, then, letting it fuel the other divisions, including music, publishing, television, and theme parks.

In short, the artistic innovations made by the storytellers through acting, singing, writing, composing, and animating were compelling executives to rethink and redirect corporate strategy. This reorientation, of course, was not an easy one. Storytellers advocated, debated, even battled among themselves and with executives to make the case for their bold creative decisions. What emerged was transformative: investment in traditional and unexplored approaches to telling stories, development of new technologies, and steps forward in the representation of women and people of color. In short, the storytellers were crucial to the company’s “Renaissance” just as much if not more so than the executives who have so often taken and received the credit.

And this dynamic has continued to bolster Disney. In the nearly two decades that Robert Iger has run the company, the power and influence of stories has been undeniable. Under his leadership, Disney has purchased and developed some of the most popular and profitable media franchises of all time through the acquisitions of Pixar (2006), Marvel Entertainment (2009), Lucasfilm (2012), and 21st Century Fox (2019). Upon his surprising return to the company in 2022, Iger noted, “I fundamentally believe that storytelling is what fuels this company, and it belongs at the center of how we organize our businesses.”

Read More: Bob Iger on Ron DeSantis, Creativity, and the Future of Disney

As the Walt Disney Company enters its second century, a good deal of uncertainty lies ahead. The harsh economic realities of the streaming business have provoked substantial cost-cutting, and rumors have even circulated about selling off parts of the company. On Oct. 9, the members of the Writers Guild of America (WGA) formally agreed to a new deal with the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP), ending a 5-month strike. But no such deal has yet been reached with the actors’ union, SAG-AFTRA.

Although Disney and other studios are currently tightening their belts to navigate the myriad uncertainties of the contemporary media landscape, thousands of actors struggle to make ends meet. They are fighting now for the ability to earn a stable living while telling the stories that help studios like Disney flourish. Whether Disney will step up to support its storytellers remains to be seen.

In the weeks and months ahead, Disney should keep in mind that it may have started with a mouse, but it has thrived all of these years because of its storytellers.

Peter C. Kunze is assistant professor of communication at Tulane University and the author of Staging a Comeback: Broadway, Hollywood, and the Disney Renaissance. Made by History takes readers beyond the headlines with articles written and edited by professional historians. Learn more about Made by History at TIME here.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Write to Peter C. Kunze / Made by History at madebyhistory@time.com