It's been 55 years since Sly and the Family Stone released their first hit, the psychedelic dancefloor stomper "Dance to the Music." Since then, Sly Stone, the group's leader and frontman, has lived out a life as one of America's most exuberant and chaotic rock stars. Stone brought down the house at Woodstock, got married at Madison Square Garden, partied with Jimi Hendrix, and created several classic and highly influential albums, including 1971's There's a Riot Goin' On.

But Stone also struggled with drug addiction, tax problems, and devastating personal conflict. He became infamously reclusive—going for years at a time without public appearances—and infamously disdained interviews.

On Oct. 17, however, Stone will step back into the spotlight and attempt to tell all of these stories and more in his new memoir, Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin). The book, written with Ben Greenman for Auwa Books—Questlove's book imprint—and named after his group's 1969 hit, explores Stone's musical innovations, personal demons, and efforts to bring social change to the U.S. as the frontman of one of the country's first major racially integrated, mixed-gender bands.

In the book, Stone professes to being not "role model, but real model." "Telling stories about the past, about the way your life crosses into the lives of those around you, is what people do," he writes in his distinctive shambolic, poetic style. "They're trying to set the record straight. But a record's not straight, especially when you're not."

The book is part of a larger project spearheaded by Questlove to reinvigorate Stone's legacy. Stone appears prominently in Questlove's Oscar-winning film Summer of Soul, and will also be the subject of a follow-up documentary directed by Questlove for Hulu.

In his first interview in the lead-up to the memoir's release, Stone answered TIME's questions over email. His answers are printed here verbatim.

TIME: How are you feeling these days? What was the last thing that excited you?

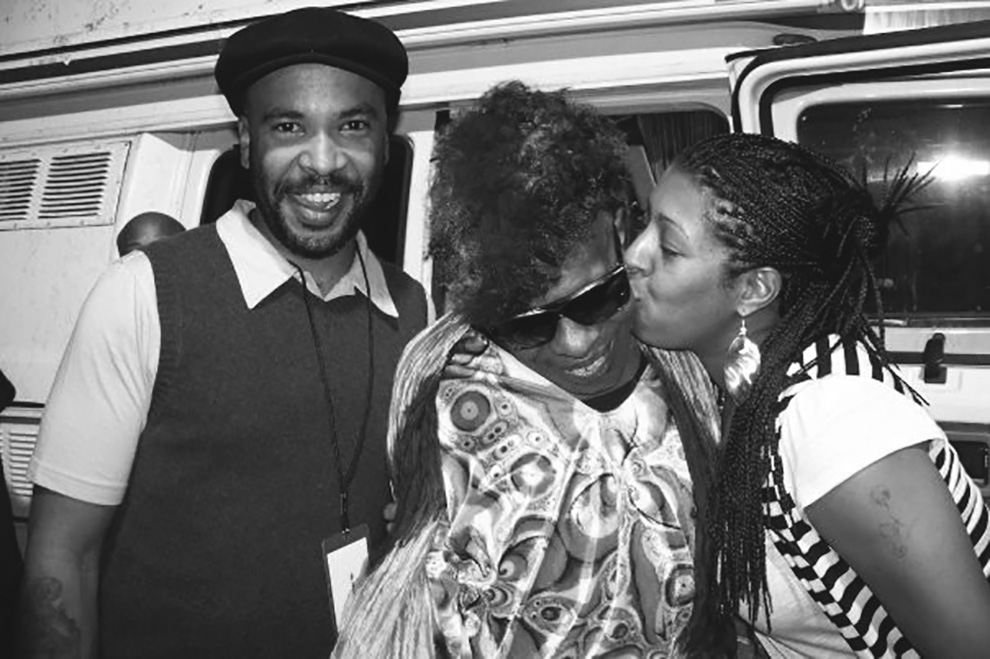

Sly Stone: I feel good in my mind but my health is not very good. I have COPD which reduces my lung capacity and other problems too. For part of this year I couldn’t hear almost at all until I got a hearing aid. The last thing that really excited me was seeing my children, and feeling the love we have for each other.

When you think back on your life, does it come back in memories? In melodies? In feelings or colors?

It's all of them. There are pictures and sounds. There are feelings and feelings about those feelings. There are stories I remember and stories I have heard about myself. Some of the stories people told about me were right on and others were right off. All of that together makes for a life story.

You wrote about this memoir: “I had to be in a new frame of mind to become Sylvester Stewart again to tell the true story of Sly Stone.” What was that process like?

People liked to say that there were two personalities in me. A doctor said it when I was in rehab, that Sylvester was welcome in meetings but Sly couldn’t come. My dad even said there were Sly days and Sylvester days. I never really thought that’s how it was. I was the same person no matter what. But there was a myth, some stories that people liked to tell that were partly true and some that weren't true at all. I had to get past some of the Sly Stone stories, and the only way to get past them was to go right through them.

In your book, you write, “Music could help you resist everyday problems. Music could keep you out of the fire.” Has your conviction about the transformative power of music changed over the years?

I know music can always make a difference. I knew it when I was on the radio. People would call into the station and say that they wanted me to play this song or that song and I could tell how much it meant to them. That was what we wanted to do with the music that we made. That’s what we did. And in a way we keep going it because old music is in the middle of some of what's coming out today. It can be in sampling or it can be in movies about concerts or festivals back then [like Summer of Soul]. It's good for good ideas and good feelings to stay alive.

Read More: Questlove on Summer of Soul and the Oscars

Was it painful for you to revisit some of the most difficult times in your life?

There were lots of things that I felt but I wouldn’t say that one of them was pain, exactly. Remembering wasn’t always easy. Sometimes things came back and other times I needed to hear the story of what other people thought happened so that I could go back there in my memory and get a clearer idea. The more I went the main thing I felt was that I wanted to forgive other people and also to forgive myself.

There’s a Riot Goin’ On is widely regarded as one of the best albums ever. Pitchfork named it the fourth best album of the 70s. Do you yourself look back on it as a high point in your life or career?

It’s hard to say a thing like that about one album or another because I was there when they were happening. I like that album but I also like Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin) and I like Fresh and I like Stand! and I like the first album we ever made. High points are for other people to think about but I am glad other people like them.

I was very moved by your recounting of your encounter with Muhammad Ali on the Mike Douglas Show, in which you wrote that the audience’s laugh got under your skin. Were there other times when you felt the world was laughing or smiling at you in moments you didn’t intend them to?

That show was cool because you could really get into a discussion. When I watch it now I remember that feeling, that it was for entertainment but there was also something at stake. Audiences weren’t always right there with us. There were concerts where I would try to talk to the crowd and they wanted a different kind of party. That happened at Coachella. There were talk shows where I wasn’t making jokes and people laughed. That happened on David Letterman.

Your memoir has a section on George Floyd. How would you compare that summer of protest to earlier ones you’ve witnessed, and why was important for you to include your perspective on that tragedy?

I still watch the news and still think about what could make things better in America. There are days when it feels like things are going in the wrong direction, that every good thing has two bad things behind it. Black and white, rich and poor, we have to find some way to live together without hurting each other. It’s not simple but it's important.

Correction, Oct. 17

The original version of this story misspelled Jimi Hendrix.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com