Over eight years, we’ve become desensitized to the outrageous—and often offensive or bigoted—things that Donald Trump says. They’ve become a regular feature of our politics, and while they ignite a temporary furor, they quickly fade into the background, with little long-term impact on Americans’ attitudes about Trump.

Yet, when it comes to his Rosh Hashanah message, which on the Jewish new year holiday attacked “liberal Jews who voted to destroy America & Israel,” history suggests there could be more staying power and political impact.

In fact, in 1990, a similar episode cost another independently wealthy Republican businessman an election after he attacked the allegiance of a liberal American Jew. The episode exposed the political perils of questioning people’s adherence to their religious faith.

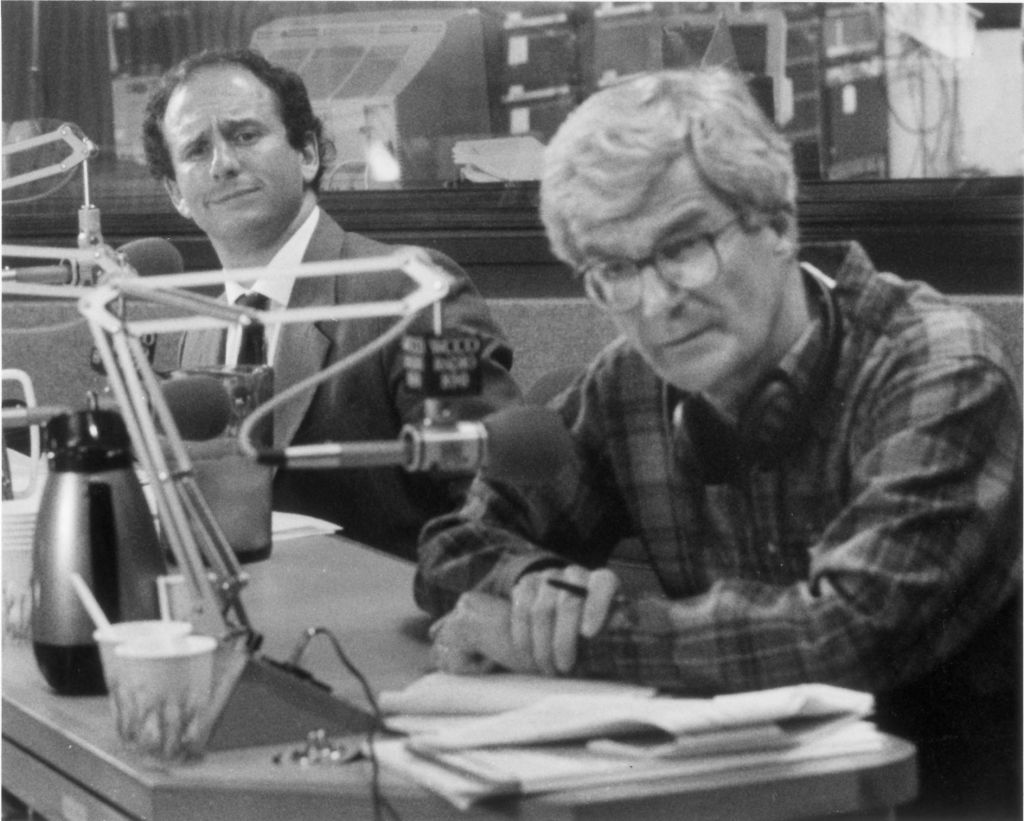

In 1990, two-term incumbent Senator Rudy Boschwitz (R-Minn.) was heavily favored to win reelection. Boschwitz was the founder of Plywood Minnesota and famous locally for his flannel shirts and milk booth at the Minnesota State Fair. Leading Democratic-Farmer-Labor (DFL, the official name of Minnesota's Democratic Party) candidates like former vice president Walter Mondale declined to run against him. Thus, the mantle fell to Carleton College professor Paul Wellstone, an experienced grassroots organizer but a political newbie save for an impulsive run for State Auditor in 1982. Early in the campaign Wellstone appeared to be little more than a speed bump for the politically connected, well-liked Boschwitz.

Read More: The History of Antisemitic Conspiracy Theories, from the Rothschilds to George Soros

Yet, after winning a contested DFL primary, Wellstone adopted what became his political signature: a green school bus that he rode around the state building a genuine grassroots effort. Despite frequent breakdowns, the bus helped Wellstone build an “everyman” image reinforced by quirky advertisements. In “Fast-Paced Paul,” Wellstone admitted “unlike my opponent, I don’t have $6 million, so I’m gonna have to talk fast,” and then appeared running scene to scene, listing his policy stances at breakneck speed. Despite being a curly-haired Jewish professor from a liberal college town in a state whose citizens knew when someone was not "one of us" (read: white, Christian, often straight), Wellstone endeared himself to unionists on the mining-dominated Iron Range and with fifth-generation farmers alike while still building support in urban Minneapolis. Ideas of economic democracy, at least in 1990, trumped identity-baiting.

By mid-October, this strategy had enabled Wellstone to overcome low name recognition and to cut a 15-point deficit in half. Boschwitz felt the heat.

As election day neared, the Republican stepped up his attacks, taking a page out of the slash-and-burn playbook that had proved so successful for George H.W. Bush and his campaign manager Lee Atwater during the 1988 presidential campaign. Wellstone was a “tax-and-spend liberal.” Even worse, he was a “self-promoting little fake.” Boschwitz’s attacks claimed his challenger “welcomed” the support of Minneapolis gangs like the Vice Lords, distributing literature on DFLers’ behalf.

This onslaught took its toll, and the progressive challenger slipped in the polls, though without the race ever feeling out of reach.

Then, the Saturday before Election Day, Boschwitz forces made a critical blunder. They circulated a letter to “Friends in the Minnesota Jewish Community,” which was written by Boschwitz supporters Ruth and Allen Aaron of Minnetonka and mailed on “People for Boschwitz” stationery including his trademark smiley face symbol. The letter read like one of the senator’s tough attack ads: Wellstone had married a Christian woman. He was raising his children outside the Jewish faith. He supported Jesse Jackson, who had embraced Palestine Liberation Organization leader Yasser Arafat and Nation of Islam leader Louis Farrakhan. “Wellstone has no connection with the Jewish Community or our communal life,” they wrote. Boschwitz, Jewish himself, was “the Rabbi of the Senate.”

The backlash was swift and severe. The Minneapolis-St. Paul media denounced the letter. Jewish community leaders condemned the invective, with rabbi emeritus Bernard Raskas of St. Paul-based Temple of Aaron noting “its appeals to religion and racism are contrary to the American concept of democracy.” Rural DFLers recounted that even their socially-conservative districts were abuzz with disapproval. Polls for the Minneapolis Star-Tribune showed Boschwitz slipping five points over the weekend, making the race a virtual dead heat.

The uproar provided Wellstone with an opportunity to reaffirm his support for a two-state solution while denouncing Israel’s “iron fist policy” of suppressing Palestinian demonstrations in the Gaza Strip and West Bank. He also decried Boschwitz’s attack on his faith and the faith of so many voters as “unforgivable.” The letter reflected poorly on the senator’s “character,” and Wellstone asserted that no candidate who would “write such a letter deserves to be a United States senator from Minnesota.”

Though Ruth Aaron denounced Wellstone as a “little whiner,” three days after her letter circulated, Wellstone pulled off a stunning two-point victory in a race where he had never led in the polls. Boschwitz's Jew-baiting backfired, the final nail in a mismanaged campaign. One Tel Aviv newspaper remarked, tongue-in-cheek, “The Bad Jew Beat the Good Jew—Thank God!”

Read More: All the Ways We Deny Antisemitism

Boschwitz apologized the following Friday, and senator-elect Wellstone accepted, praising the “tremendous amount of sincerity and conviction” in Boschwitz’s statement. But the damage had been done. The Aaron letter provided both an excuse for independents to abandon Boschwitz and an opportunity for Democrats to restate the broad humanitarian objectives of their Israel policy.

Trump’s Rosh Hashanah statement provoked less immediate backlash—probably because it’s not a particularly unusual type of attack for the former president. Many Republican voters appreciate Trump’s incendiary, sometimes bigoted rhetoric and willingness to thumb his nose at those who denounce it. Additionally, there are probably fewer undecided voters in 2023 than there were in 1990.

Yet, that does not mean Trump’s message won’t hurt him. As in 1990, it offers up an opportunity for Democrats to reaffirm their support for a humane resolution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and for American Jews at a time of rising antisemitism. It also could backfire with devout Americans of all religions, who find questioning people’s faith offensive. Certainly in 1990, voters in overwhelmingly Christian Minnesota blanched at making someone’s faith practices a public matter and in just a few days abandoned Boschwitz.

While we won’t see a similarly immediate impact on Trump’s political standing, he has still ventured into territory that could prove damaging, especially in a close election.

Cory Haala serves as assistant professor of history at the University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point and is a political historian of the Midwest and American liberalism. Made by History takes readers beyond the headlines with articles written and edited by professional historians. Learn more about Made by History at TIME here.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- How Far Trump Would Go

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- Saving Seconds Is Better Than Hours

- Why Your Breakfast Should Start with a Vegetable

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Ryan Gosling

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Cory Haala / Made by History at madebyhistory@time.com