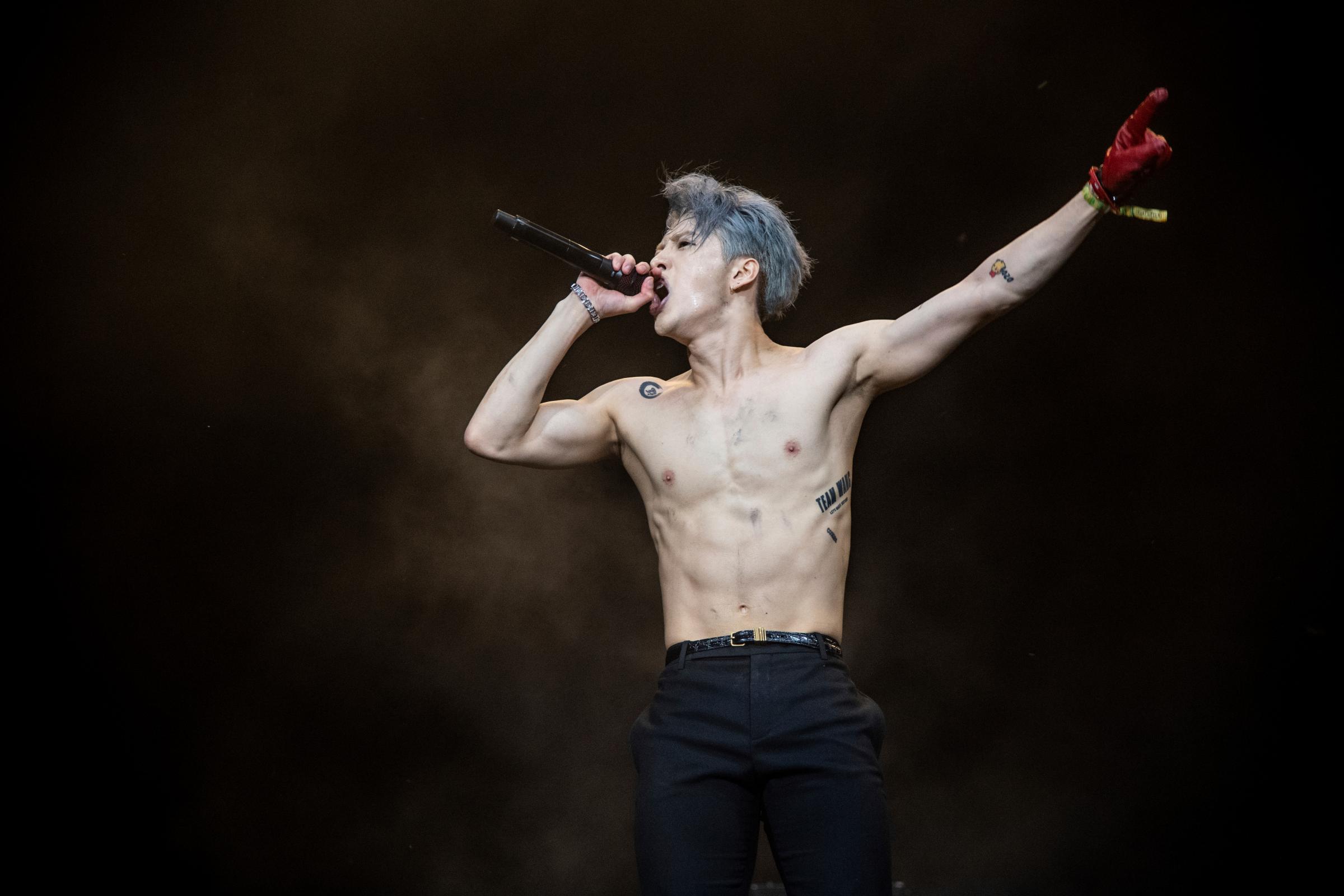

88rising, a U.S.-based media company-cum-record label, set out eight years ago to bring Asian artists to the fore of the American hip-hop scene—and it’s been wildly successful. The group’s flagship music festival Head in the Clouds debuted five years ago at the Los Angeles State Historic Park and has since been dubbed the “Asian Coachella,” showcasing the likes of Japanese YouTube personality and singer Joji, Indonesian rapper Rich Brian, and Hong Kong-born K-pop bandmate-turned-solo act Jackson Wang before audiences in bigger and bigger venues across Los Angeles, New York, and even globally in Manila and Jakarta.

Alongside the recent surge in popularity of K-pop, as a producer and promoter 88rising has played a pivotal role in narrowing the gap between the Asian and Western music industries. Its affiliated artists have topped charts internationally, soundtracked Marvel movies, and been embraced by massive festivals and stages around the world.

But increasing Asian representation in mainstream hip-hop outside of Asia was only half of 88rising’s goal. It also sought to bring American-style hip-hop to Asia, and now its sights are set on the most ambitious crossover yet: staging its Head in the Clouds festival in China, which offers the lucrative potential of a massive market but requires navigating the risks of delicate geopolitics and historic censoriousness.

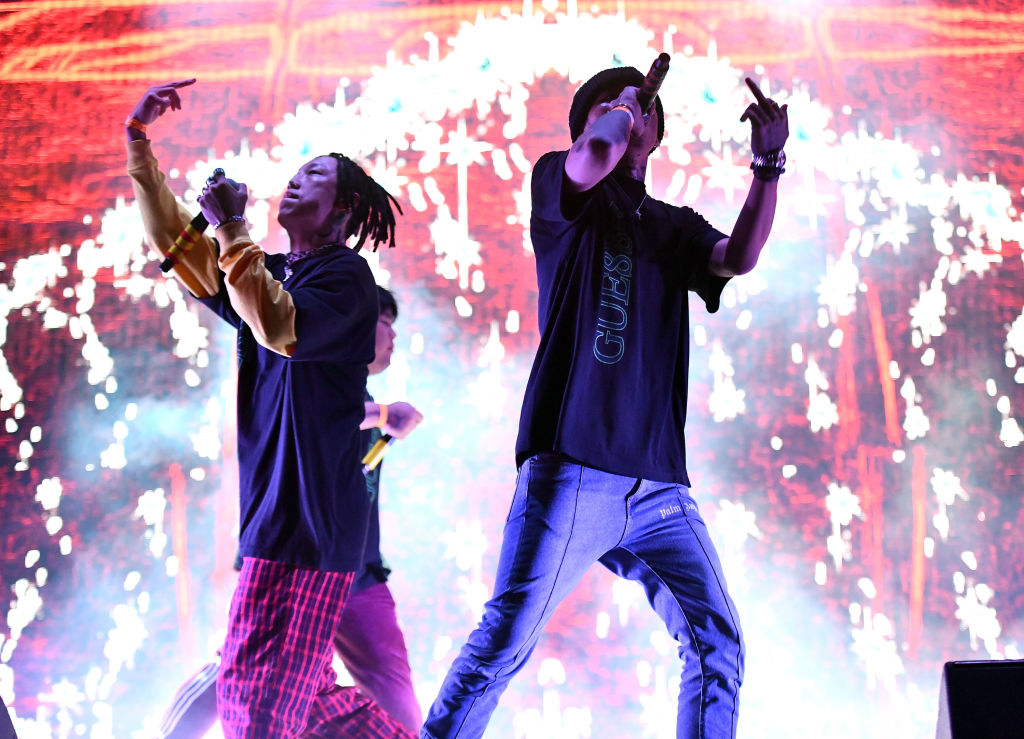

China has always been a part of 88rising’s equation: the company’s only other office outside of New York is in Shanghai. And many on its roster of artists hail from China, including rap crew Higher Brothers. But finding Chinese talent and appealing to Chinese audiences are one thing; putting on an American-produced show in the country is much more complicated.

But that’s exactly what the company plans to do this weekend, holding a historic first Head in the Clouds festival in Guangzhou, a city in the southern Chinese province of Guangdong, where up to 25,000 fans are expected to turn out to see performances by a long lineup of global artists, including Rich Brian and Higher Brothers as well as a number of local artists from Guangdong.

“Our core position is an Asian youth culture company,” says Jackson Wong, 88rising’s China president. (88rising’s co-founder and CEO Sean Miyashiro declined to comment on the record for this story.) “But for us, I mean, we are a global company, and China is part of the global footprint, so I don’t think we can totally stay away or ignore the market.”

In March, the Chinese state news Global Times announced that the country is open to international performances again after a three-year suspension due to COVID-19. But even before the pandemic shut everything down, Western artists haven’t been the most welcome in China.

American rapper Jay-Z and Canadian pop singer Justin Bieber are among those who have been banned for “vulgar language” or just being deemed generally inappropriate. “In order to maintain order in the Chinese market and purify the Chinese performance environment, it is not suitable to bring in badly behaved entertainers,” China’s culture ministry stated in 2017 about barring Bieber. Others, meanwhile, like British and American rock bands Oasis and Bon Jovi, Icelandic singer Björk, and U.S. popstars Lady Gaga and Katy Perry have been blacklisted for political statements, including perceived support for Taiwan or Tibet. Some, like famous protest-song singer Bob Dylan, have had to have their setlists approved in order to grace the stage in China.

Even for those who are allowed to enter China without explicit restrictions, experts tell TIME the rules around acceptable performance are notoriously vague and encourage self-censorship. In May, multiple events ranging from concerts to a tech convention were abruptly canceled with little explanation from authorities, leaving performers to form their own theories of what triggered the crackdown.

“Sometimes the red line is not that clear,” says Nathanel Amar, an associate researcher at the Hong-Kong based French Centre for Research on Contemporary China. “You don’t know where the line is. So if [artists] want to continue performing in China, they have to be careful when they do live performances.”

Read More: China’s ‘Voice’ Represented Hopes and Dreams—It Turned Around to Reveal a Darker Reality

Domestic musicians, too, deal with similar limitations, and hip-hop artists, especially, have found themselves having to straddle the fine line between representing the genre’s characteristic unruly spirit and staying out of trouble with the government. “It’s very important for hip-hop artists to not lose the authenticity of ‘keeping it real,’ which is a common mantra in the hip-hop world that [the] Chinese audience cares about,” says Yehan Wang, a sociology researcher at the University of York. “This is a really challenging point to balance.”

Though an underground hip-hop scene first emerged in China in the 1990s, the genre rose to prominence with the reality competition TV show The Rap of China, which first aired in 2017. “This kind of mainstream popularity,” says Wang, “confirmed that Chinese hip-hop can exist in forms that are suitable for Chinese audiences as well as compatible with Chinese culture.”

But it wasn’t immediately compatible with the Chinese Communist Party. Two of the program’s winners were sanctioned. Wang Hao, who went by the stage name PG One, was lambasted for his “lewd lyrics” and “low-taste content,” and he has since struggled to make a comeback. Zhou Yan, known as GAI, was abruptly pulled from another popular television show in 2018 amid the state’s crackdown on hip-hop. By the time he returned to the entertainment scene, he had ditched his initial gangster persona and turned to spitting patriotic rhymes that celebrated China’s rich culture and history. That kind of lyrical pragmatism has come to be the norm. In 2021, 100 Chinese rappers collaborated in a song to celebrate the CCP’s centennial—though the track ended up getting scrubbed off the web after being widely panned.

“If Chinese hip-hop artists want to go mainstream, publish albums, be on TV shows, continue to do well in terms of sales and views … they have to be co-opted at some point,” says Amar. “They have to tone down their rebellious spirit and go in line at some point with the guidelines.”

These issues aren’t new to 88rising. “Every market has its approval process,” Wong, the part-management, part-marketing company’s China president, tells TIME. “We cannot just copy and paste what’s happening in the U.S. or globally … into the Chinese market. We need to respect the local audience.”

In 2018, Chinese social media users started accusing 88rising of being anti-Chinese and supporting the Tibet independence movement, after the Tibetan flag was reportedly included in the company’s early promotional material. In response to the backlash, according to The New Yorker, CEO Miyashiro dialed down the marketing strategy for a single that was soon to release, deciding that it “wasn’t worth the potential drama.”

Artists linked to the label have also previously made adjustments to avoid ruffling feathers, not just in Beijing. Rich Brian changed his stage name, which used to be Rich Chigga, in 2018 amid criticism of appropriating an American racial slur. And Melo of Higher Brothers went viral on Chinese social media in 2015, before Higher Brothers joined 88rising, when he rapped in a song about the rideshare app Uber: “I don’t write political hip-hop. But if any politicians try to shut me up, I’ll cut off their heads and lay them at their corpses’ feet.” Chinese censors promptly took the rap down, and authorities brought him in for questioning. Since then, Melo and the rest of Higher Brothers have steered clear of politics—unless it’s explicitly pro-China.

88rising has also already had experience navigating conservative environments in the region, having brought Head in the Clouds to Jakarta last year, where live music is similarly strictly regulated. That said, a single-day 88 Degrees & Rising concert, originally set to be held earlier this month in Jakarta, was abruptly canceled, though the reason was unclear.

Wong acknowledges part of the process of staging Head in the Clouds in Guangzhou involved informing authorities of what songs would be performed. He did not answer whether any songs were self-censored or altered at authorities’ request but said that more of the focus was on “our creative decisions around our installation … and more operational stuff like how the crowd [gets] into the whole festival grounds, how they exit it.”

Five years ago, 88rising ushered in its festival-staging era with a Head in the Clouds mixtape, featuring a number of collaborations by its artists. As the company enters a new era in China, it’s unlikely—though not impossible given the almost arbitrary nature of censorship—the audience in Guangzhou will get to hear the popular lead single, Midsummer Madness. Back then, Joji, Rich Brian, Higher Brothers, and AUGUST 08 led a refrain of “F-ck the rules”—almost emblematic of 88rising’s disruptive ascendancy. Now, however, to succeed in China, it’s more likely they’ll be following the rules.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com