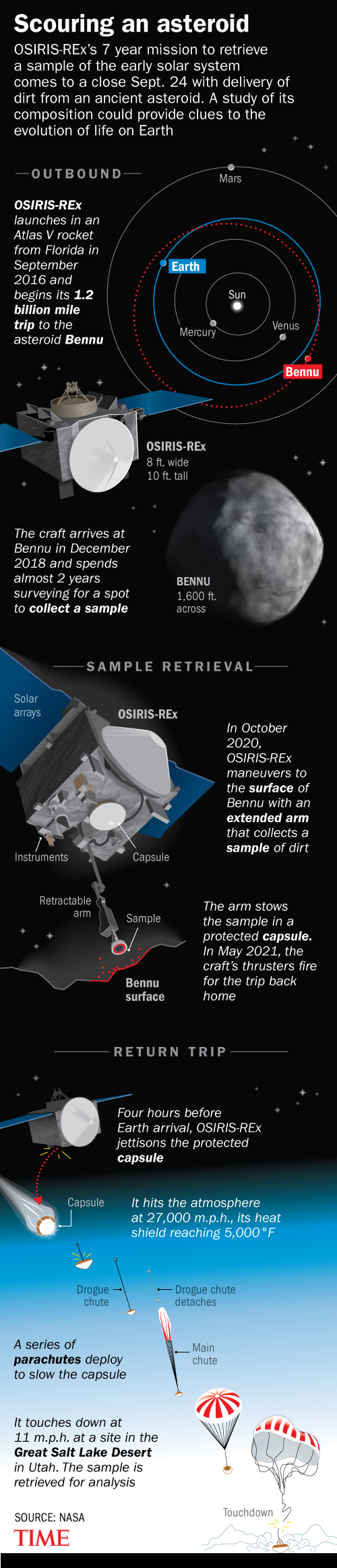

Infrared sensors on the ground detected the heat signature of the OSIRIS-REx spacecraft’s sample-return capsule when it slammed into the atmosphere at more than 45,000 km/h (27,650 mph), at 8:42 a.m. MDT today. The 46 kg (101 lbs.) capsule was dropped off by its much larger OSIRIS-REx mother ship as that spacecraft went whizzing briefly by Earth. The capsule hit the air off the coast of California, aiming for a parachute landing in the Department of Defense’s Utah Test and Training Range southwest of Salt Lake City. Even before the capsule landed, four search helicopters scrambled to meet it, and the people at NASA waited anxiously to hear that it had returned safely.

It had. The capsule thumped down at 8:55 a.m. MDT and the helicopter crews scooped it up and whisked it to a clean-room on the military base, preparing to send it off to the Johnson Space Center in Houston.

The scientists there will have a lot to look at. Sealed inside the capsule are 250 gm (8.8 oz.) of rock and dust from the asteroid Bennu—a 4.5 billion-year-old fossil of the ancient solar system that NASA has spent more than $800 million and seven years working to explore. The return of the sample made OSIRIS-REx only the third spacecraft—and the first American one—to pull off the asteroid-spelunking trick, after Japan’s Hayabusa and Hayabusa 2 managed it in 2010 and 2020 respectively. Understand the chemistry and history of Bennu’s dust and you can understand the chemistry, history, and even origins of the solar system and the Earth—as well as the life that calls our planet home.

“It sort of speaks to the reasons people explore,” says Rich Burns, the OSIRIS-REx project manager. “We can learn about the evolution of the solar system, why the Earth exists in its present state, why it’s special. We can get at the question of where we come from.”

Collecting that Bennu sample was not easy. It was on Sept. 8, 2016, that OSIRIS-REx (short for Origins, Spectral Interpretation, Resource Identification, Security-Regolith Explorer) lifted off from Cape Canaveral in a round-about pursuit of Bennu. The asteroid is a small target—just 492 m (1,614 ft.) across—and circles the sun in more or less the same orbit as the Earth. At its most remote, it is about 300 million km (186 million mi.) from us. The most direct way to reach it would be to cut across the solar system in an as-the-crow-flies pursuit, intercepting Bennu on the other side of the sun. But that would have seen the spacecraft approaching the rock at a 90-degree angle, blazing past it at 19,300 km/h (12,000 mph). That’s fine for the kind of brief, photographic flybys the Voyager spacecraft conducted of the outer planets in the 1970s and 1980s; the OSIRIS-REx mission, however, called for the spacecraft not just to fly past Bennu, but to enter a lazy orbit around it. To do that, the ship had to make two complete circuits around the sun, slowly catching up to the asteroid and matching its speed and trajectory. During that time, OSIRIS-REx put more than 2 billion km (1.24 billion mi.) on its odometer.

On Dec. 3, 2018, the spacecraft at last caught up with Bennu and fired its thrusters to enter orbit around the rock. It took barely a puff of propellant to do that, and it would take just as little to pull away: Bennu’s gravity—to the extent that it has any at all—is 100,000 times less powerful than that of Earth. Settled into the asteroid’s tenuous gravitational grip, the spacecraft began a remote surveying campaign, using its multiple on-board instruments—including three cameras, an infrared spectrometer, an X-ray imaging spectrometer, and a laser altimeter—to study Bennu’s mineral and elemental makeup. It also exhaustively mapped the asteroid’s surface, looking for a place to collect its sample. At some points, OSIRIS-REx flew at altitudes as low as 1.6 km (0.99 mi.) above Bennu—the closest any spacecraft has ever gotten to any body it was orbiting.

Read more: Scientists Solve the Mystery Behind the Oumuamua 'Alien Spacecraft' Comet

Drawing so close came with perils. Bennu rotates on its axis once every 4.3 hours—giving it 2.15 hours of sun-facing day, and 2.15 hours of space-facing night. During those transitions, the temperature on any given spot on the rock swings from 116°C (240°F) to -73°C (-100°F) and back again. All those changes in thermal pressure make for a lot of expansion and contraction of the rocks and other rubble on the surface—enough to make them, effectively, leap off Bennu’s surface.

“It ended up looking like popcorn,” says Dante Lauretta, professor of planetary science at the University of Arizona and principal investigator on the OSIRIS-REx mission. “Every time we looked we saw stuff exploding off the surface. We were saying, ‘Oh man, this could be a hazardous environment for the spacecraft. We might have to back away and redesign the whole encounter.’” Ultimately the team concluded that that wouldn’t be necessary. It doesn’t take much energy for small rocks to pull free from Bennu’s microgravity grip, so even if the rubble struck the spacecraft it wouldn’t be packing any meaningful wallop.

All of the up-close orbital scrutiny the rock got paid off: just a week after the spacecraft arrived at Bennu, NASA announced that it had discovered the presence of hydrated—or chemically water-logged—minerals mixed in with the soil. With no atmosphere and its mere whisper of gravity, Bennu could not harbor any deposits of pooling liquid, but the finding of even traces of water does suggest that the rock was once part of a much bigger mass—perhaps even a moon or planet—that did have muscle to hang onto its water.

“The thinking,” says Burns, “is that Bennu was part of a larger parent body that had a collisional event.”

It wasn’t until Oct. 20, 2020, nearly two years after OSIRIS-REx arrived at Bennu, that the spacecraft began the capstone maneuver of its mission—descending that last mile to collect its sample. NASA had narrowed the potential collection sites down to four candidates that it dubbed Sandpiper, Osprey, Kingfisher, and Nightingale—choosing those because they had the fewest rocky obstacles for the spacecraft’s descent, as well as abundant loose soil to collect. Ultimately NASA determined that Nightingale—located in a crater high in Bennu’s north—was the best of that group.

Taking the sample required the spacecraft to land briefly on Bennu, in a maneuver NASA named TAG, for touch-and-go. In the 16 seconds OSIRIS-REx was on the surface, it extended its 3.3 m (10.8 ft.) robotic arm, which was equipped with a collection chamber at the end. At that point, nitrogen bottles in the arm fired, blowing soil and loose pebbles into a chamber. The lid to the chamber was then sealed and the precious sample transferred to the return capsule. On May 10, 2021, after completing nearly seven more months of orbital surveying, OSIRIS-REx at last peeled off and headed back for Earth.

Read more: NASA Tried To Knock an Asteroid Off Course—And Succeeded Wildly Beyond Expectations

With the Bennu sample now on the ground, more than 200 scientists from around the world will set to work studying it. The most intriguing questions they’re trying to answer concern the role incoming asteroids may have played in seeding the Earth with water, nitrogen, carbon, and other ingredients necessary for life to take hold.

The moon is believed to have formed close to 4.5 billion years ago, when a Mars-sized planetesimal collided with Earth, throwing up a cloud of debris that coalesced into a brand new body. Any oceans, much of the atmosphere—and any potential earthly biology—that may have existed on our planet would have been wiped out in the violence. “We think the surface was completely sterilized,” says Lauretta. For life to reemerge, it would take asteroids crashing into Earth and resupplying it with the necessary chemistry. Studies of Bennu’s soil and rocks will help show if asteroids indeed carry sufficient quantities of those raw materials in the first place.

And as for OSIRIS-REx itself, which did not even pause in this morning’s flyby of Earth? Originally, the spacecraft’s mission was supposed to end after the sample-return capsule was released. In April 2022, however, NASA announced that it had other plans for the ship, and would be sending it off for a second orbital rendezvous, this time with the asteroid Apophis, after the 340-meter (1,100 ft.) rock makes a close approach by Earth in 2029. OSIRIS-Rex will spend about 18 months at Apophis—and some members of the team are dreaming that it may not be finished even then.

“Never say never,” says Lauretta. “I’m stepping down as the principal investigator and one of my mentees is taking over. I told her, ‘Don’t break the spacecraft. It might have a third asteroid in it.’”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Jeffrey Kluger at jeffrey.kluger@time.com