This article is part of The D.C. Brief, TIME’s politics newsletter. Sign up here to get stories like this sent to your inbox.

Every also-ran candidate for the presidency has the same notion: all they need to slingshot to the race’s top tier is a breakout performance at a nationally televised debate. They spend days—or weeks, in some cases—studying their rivals’ records, honing their barbs and finding the perfect parry to dodge the inevitable incoming. Even the non-lawyers are suddenly freelancing as prosecutors in a fan-fic roleplay unfolding in hotel conference rooms and the back of campaign buses.

Most of the eight candidates who have landed a spot on the stage for the first Republican debate would be wrong to think they are going to go up there and clobber the competition. In fact, they are all likely approaching the opportunity with the wrong mentality. The stakes could not be more significant—not to win, but to dodge a faceplant.

In fact, primary debates—like the one on Wednesday in Milwaukee—can definitely serve up more damage than advantage. Every campaign veteran knows the greatest hits of debate flubs. And in primaries in particular, voters respond with little mercy. In fact, one academic study found that 60% of voters changed their minds after watching primary debates, far lapping the 14% of minds that are historically changed because of the general election debates.

And those were debates that included the frontrunner. Ex-President Donald Trump has said he plans to skip Wednesday’s meeting and its follow-ups. After all, he’s so far ahead of the pack, why punch down?

(My TIME colleague Molly Ball, whom I will hopefully be sitting next to in Milwaukee this week, has a terrific dispatch from Iowa about why Trump’s rivals don’t think he’s on as sure of a footing as he projects. A new NBC News poll of Iowans finds both Sen. Tim Scott of South Carolina and Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis ahead of Trump when it comes to net favorability there. It’s why The D.C. Brief has argued Trump’s rivals might want to rethink their assumptions. And, let’s be clear: Iowa can be funky in a good way.)

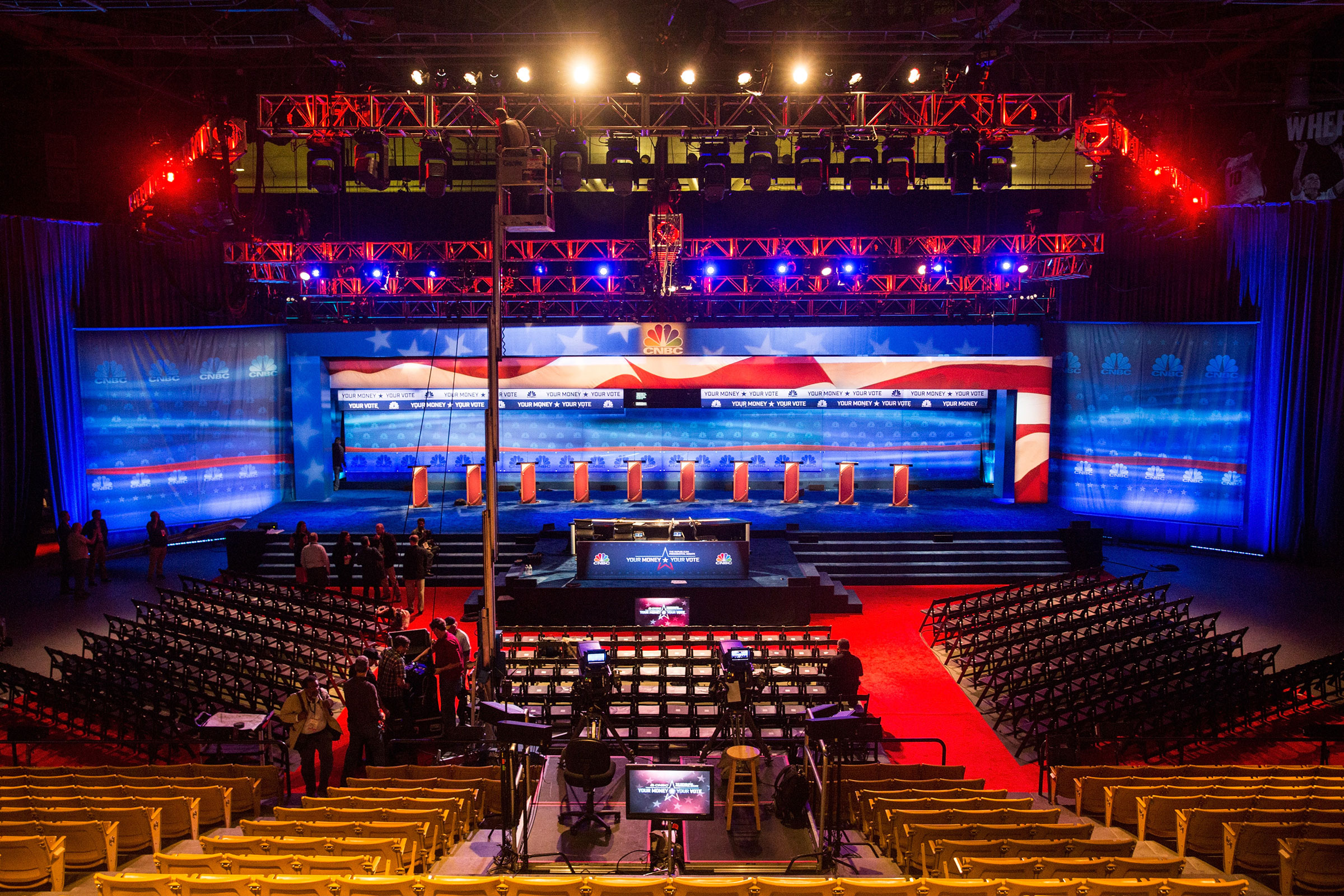

Still, there will be plenty of gawkers at the events unfolding on a stage organized by the Republican National Committee and its broadcast partners at Fox News.

Advisers always have to balance their advice with a mix of caution and confidence. No one can deny that then-Mayor Pete Buttigieg’s talents took him from a curiosity to the winner of Iowa’s lead-off caucuses in 2020. (A killer ground game and loyal donor pool of LGBTQ pockets helped, too.) Eight years earlier, then-former Massachusetts Gov. Mitt Romney finally found his debate footing after the best coach in the business, Brett O'Donnell, joined the team for a spell. (Days later and with Romney finally coasting toward the nomination, the Romney campaign and O’Donnell parted ways.) And in 2008, Arkansas Gov. Mike Huckabee used his skills honed as a televangelist and pastor to capture the GOP’s imagination.

But for every Buttigieg and Huckabee, there are dozens of more common cautionary tales. And while every candidate will have a snitty retort to each potential incoming barb and another one teed up to build on those volleys, they would do to remember this truth: no one is more of a threat to every single person on that stage than themselves.

You see, recent history is brimming with examples of candidates who all but ended their candidacies through uneasy, unmoored, or unhinged debate showings. In 2019, former Rep. Beto O’Rourke of Texas stabbed the balloon of sky-high expectations of his candidacy with a broadsword of a meltdown in Miami. The moderator chided him for dodging questions, and his rivals took direct aim at him on the two issues that would define the Democratic primary—health care and immigration—and his Spanish-language answers got meme’d. (And not in a good way.)

So bad was that night, his campaign manager came to meet reporters that night wearing the bravest face she could muster. “Clearly, a lot of people had interest in connecting with us, and that's great because that means that people are looking at us, they feel like that we have something to say, it's important to say, and we had a lot of opportunities to lean in on our substance and our policies," Jen O'Malley Dillon said.

After a follow-up performance on Oct. 15, near Columbus, Ohio, went just as badly, O’Rourke’s favorability numbers with Democrats predictably tanked by almost 6 percentage points—the biggest slump in the field. By Nov. 1, O’Rourke joined the ranks for former candidates. Less than six months later, O'Malley Dillon was named the new manager for Biden’s campaign and made history as the first woman to lead a successful Democratic nominee.

Other examples abound. Former Minnesota Gov. Tim Pawlenty planned to show voters he was a tough guy who would take the fight to Romney in 2012. He rolled out ahead of time a new epithet: “Obamneycare,” a Frankenmashup of Obamacare and Romneycare. But when the debate finally arrived, Minnesota Nice got the best of Pawlenty, who, standing feet from Romney on stage, couldn’t bring himself to bring down the hammer he had been flaunting for days. As NPR asked: “Why did Tim Pawlenty both throw a grenade and then throw his body on the same explosive he had just lobbed?”

Later that cycle, then-Texas Gov. Rick Perry promised to slay three federal Cabinet agencies but could only name two. “Oops” might as well have been the epitaph on his national political career. (The agency he wanted to scrap? He later led it in the Trump Administration.) And who can dismiss Ronald Reagan’s 1980 protest against George H.W. Bush at a debate he bankrolled amid campaign finance disputes in Nashua, N.H.?: “I am paying for this microphone, Mr. Green!"

Here, a caveat is in order. A bad debate night does not instantly usher a campaign into the archives. In 2007, Hillary Clinton had a nightmarish night on Dartmouth’s campus in northern New Hampshire as everyone finally decided to team up against her. In Philadelphia a few weeks later, the issue of drivers licenses for undocumented immigrants dogged her. Even her likeability chased her—and lured Barack Obama into a gaffe of his own when he declared Clinton “likable enough” in a comment that rang much differently for women than men. Clinton would defeat Obama days later in New Hampshire and set in motion a protracted fight for the nomination that really only ended when the pair arrived in Denver for the nominating convention. She didn’t win the nomination, but she got to be America’s top diplomat for four years.

To be clear: none of this is exactly good training for the job these people are trying to land. Presidents do not spend their days debating rivals; President Joe Biden and House Speaker Kevin McCarthy haven’t jousted in person for months. The closest scenario of give-and-take conversations with a room of skeptics is a news conference, and, through the end of July, Biden has averaged about 11 such meetings with reporters annually. But in the United States, an ability to stand at a podium and defend one’s positions has come to serve as a proxy for what voters are most looking for in a commander in chief: mental acuity, the confidence and polish to represent the country around the world, and the temperament to be a credible father—yes, still male—figure for the nation.

So, as a Trumpless cohort of Republicans who want to replace Biden assemble like the Avengers sans Captain America (or maybe the Incredible Hulk better fits the analogy), it’s worth asking the most basic questions: Can any of these eight candidates put themselves on better footing Wednesday night than they were beforehand? Or is the best any of them can hope for is not losing ground?

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- How Far Trump Would Go

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- Saving Seconds Is Better Than Hours

- Why Your Breakfast Should Start with a Vegetable

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Ryan Gosling

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Philip Elliott at philip.elliott@time.com