It’s easy to spot the small, family-owned fishing boats that ply the waters around Baja California—a peninsula 1,223 km (760 miles) long that represents the westernmost part of Mexico. There are 24,000 of the vessels, after all, and they spend much of their time at sea—as well they might if the so-called artisanal fishermen are going to compete with the vastly larger industrial vessels that fish the same waters. The average artisanal boat measures 24 m (79 ft.) from bow to stern, compared with the industrial vessels, which can easily exceed the length of a football field, at 130 m (427 ft.). And the industrial vessels are equipped accordingly—with nets that measure 600 m (1,968 ft.) across, and baited lines that may stretch 45 km (28 miles) long.

“There’s a huge level of injustice there,” says Cristina Mittermeier, a photographer, marine biologist, and co-founder of the U.S.-based ocean-preservation group SeaLegacy, which is partnering with the Mexico-based group Beta Diversidad to address environmental and economic problems around Baja California. “The industrial fishing fleet is owned by billionaires and subsidized by the government.”

More From TIME

The kind of megafishing the industrial boats do leaves a huge environmental footprint. Up to 96% of the population of bluefin tuna in the region are gone, for example. For every 2.2 lb. of shrimp pulled from the ocean, there are more than 20 lb. of unwanted bycatch—mostly juveniles of various species. The nets drag along the bottom of the ocean, damaging the delicate ecosystem of the ocean floor, and releasing the carbon that’s sequestered in the sediment.

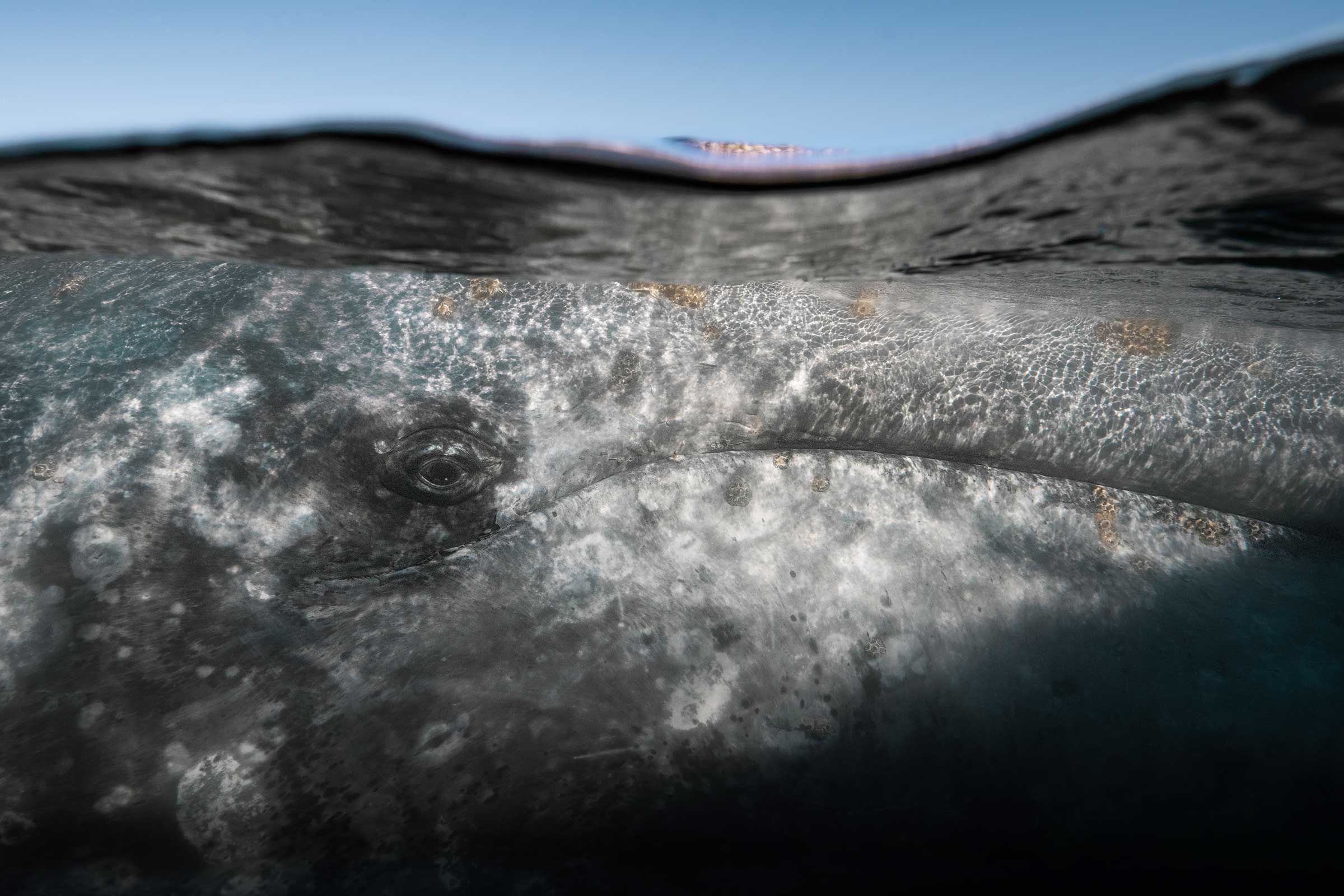

It’s not just the industrial fishing boats that are making a mess of these waters. It’s tourists too. “Ecotourism” generally has a benign sound to it, conjuring up images of respectful whale watchers looking for the great creatures from quiet boats, idling at a distance. But things aren’t nearly so peaceable. “Unregulated tourism affects species like whales, orcas, marlins, sea lions, and dolphins, thanks to overcrowding of boats with no permits,” says Mario Gómez, president of Beta Diversidad.

“There can be 30 boats chasing one orca,” says Mittermeier. “I was in one of those boats 15 years ago … All of the whale sharks [we saw] had propeller marks on them.”

But there’s a fix for all of this—with historical precedent. In 1995, the Mexican government, pressed by local activists, created the Cabo Pulmo National Park on the southeastern tip of Baja California—covering both land and a portion of the offshore region. Cabo Pulmo once saw much of the devastation that the rest of Baja California is suffering. But not anymore.

Industrial fishing is prohibited, and ecotourism is heavily regulated. The result has been a 465% increase in the population and diversity of fish in the local waters and a recovery of the region’s damaged coral reef. In 2005, Cabo Pulmo was named by the U.N. as a UNESCO World Heritage site.

“It became such a famous place,” Mittermeier says. “And now people are saying, ‘Oh, we need more Cabo Pulmos.’”

Read more: One Man's Quest to Heal the Oceans—And Maybe Save the World

SeaLegacy and Beta Diversidad, along with other environmentalists, are working to make that happen, leading a movement to create a protective zone that will fit like a sock over the southern half of Baja California—where the peninsula’s greatest biodiversity is found—extending into the waters of the Gulf of California to the east of Baja and the Pacific Ocean to the west. Some sport and artisanal fishing will be allowed near the coasts, and a tightly regulated ecotourism industry, but no industrial fishing. Farther out into the ocean will be a “no take” zone that will leave part of the Pacific and the Gulf of California entirely untouched.

“The tension really is to preserve the traditional way of life of fishermen and preserve the economic activity of tourism but with a regulation framework, so that it’s not a free-for-all,” says Mittermeier.

Beta Diversidad, SeaLegacy, and other environmental advocates plan to present their proposal in a formal request to Humberto Adán Peña Fuentes, Mexico’s Commissioner of Natural Protected Areas. It would be up to Fuentes to approve the request and then pass it on to President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, who has the power to designate or deny the marine reserves.

“In the case of this designation, the most important group to protect are the artisanal fishers, because their livelihood is fully impacted,” says Gómez. “That is what really triggers the commissioner’s interest.”

The advocates are hopeful—but time is short. Mexico’s presidential campaign begins in November, with the election taking place next June. Environmentalists expect Fuentes to make his recommendation to López Obrador near the end of the year, and in turn expect López Obrador to make his decision shortly after.

Until then, the matter of Baja California remains very much open to question—and that leaves supporters of a protected zone committed to telling the tale of their effort as widely and loudly as possible. “I’m supporting this with all I have because humanity needs it,” says Mittermeier. “Without stories, the ocean dies in silence.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Jeffrey Kluger at jeffrey.kluger@time.com