Vivek Ramaswamy is in a crowded Ford Explorer zooming through New Hampshire. It's early August, and the Republican presidential candidate is racing between campaign stops, taking questions from three reporters while strategizing with a campaign aide. At one point, the SUV shakes as his driver veers onto the highway's rumble strip, but Ramaswamy looks only momentarily startled before launching back into a response.

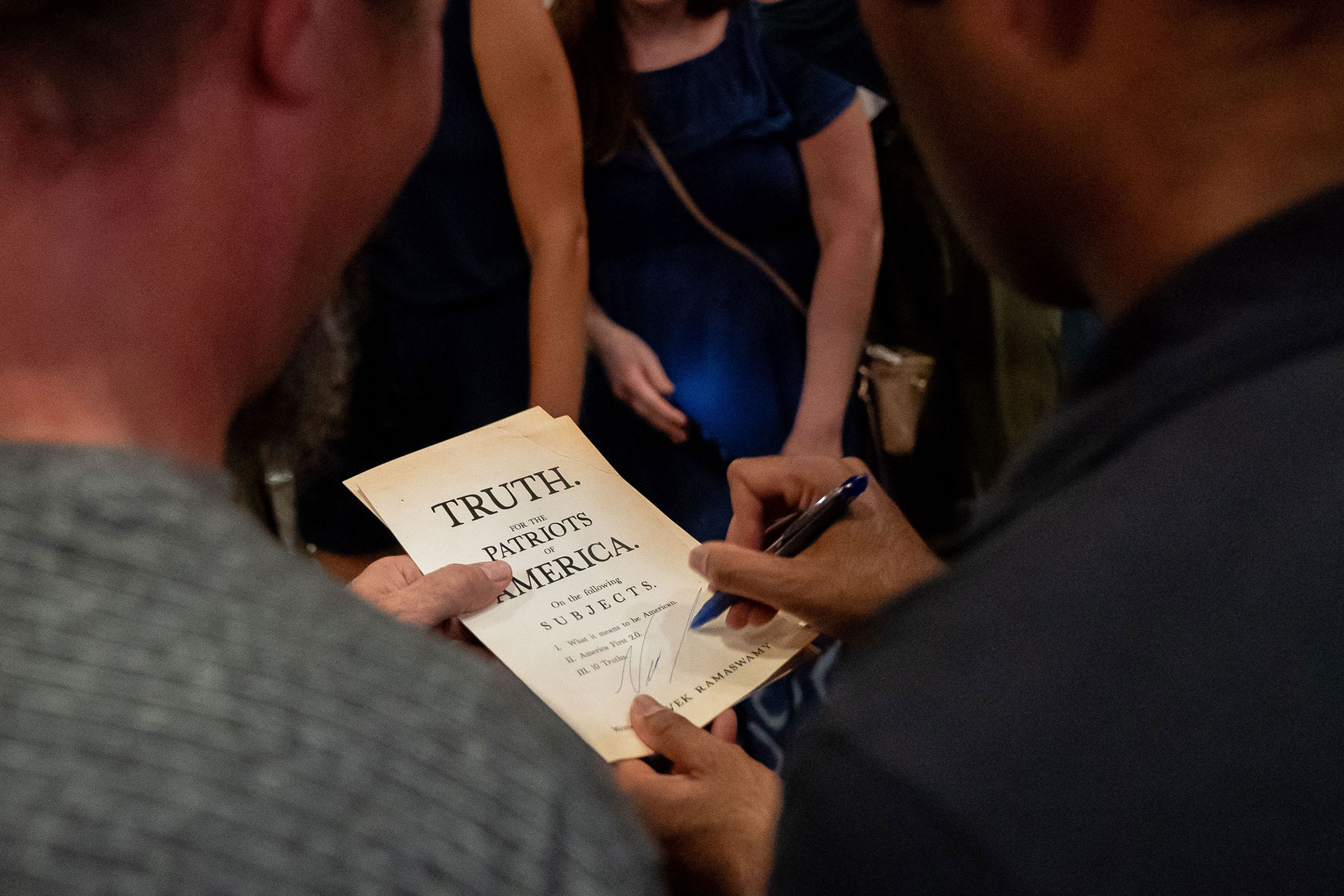

Every presidential candidate needs to be able to do more than one thing at a time—to walk and chew gum, hold babies and deliver speeches. But nobody in the GOP field multitasks quite like the uber-wealthy Ramaswamy, 38. He's already had a busy day, jetting from Washington—where he visited the courthouse where Donald Trump was about to be arraigned to express his outrage—to the Granite State, where he took questions at a lunchtime meet-and-greet and a backyard party. His team blanketed both events with pamphlets listing Ramaswamy’s 10 “truths.” (Among them: “there are two genders,” “human flourishing requires fossil fuels,” and “the nuclear family is the greatest form of governance known to mankind.”) The first-time candidate told attendees about his plans to eliminate the Department of Education, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, and the Internal Revenue Service. And he said he'd take “America First” even further than Trump, by pulling back on support for Ukraine and deploying troops to secure the southern border.

The everywhere-all-at-once strategy, and the former biotech tycoon's talent for presenting bomb-throwing anti-establishment sentiment in an affable package, has made him the closest thing the GOP primary has had to a breakout star. Since launching his campaign in February, Ramaswamy has been going nonstop: shaking hands in New Hampshire, rapping Eminem verses in Iowa, appearing on more than 70 podcasts and nearly every news program that will have him, and producing a stream of online content more voluminous than any of his competitors. Suddenly, Ramaswamy is running in second or third place in multiple national polls and often outperforming governors and a former vice president in the early states.

Sarah Longwell, an anti-Trump Republican pollster who regularly conducts focus groups with GOP-leaning voters, says her panelists used to bring up Florida Governor Ron DeSantis unbidden, while mentioning Ramaswamy barely at all. Now the situation has reversed. “I think that he has been running the kind of campaign that Ron DeSantis should have run,” Longwell says of Ramaswamy.

That doesn't mean Ramaswamy's road from here will be easy. Trump remains the dominant force in the race, earning the support of a majority of primary voters in most recent national polls. And none of Ramaswamy's rivals have turned their fire on him yet, in part because he hadn't been seen as a threat. While he's making a name for himself with the GOP base, Longwell still doesn’t view Ramaswamy as a serious candidate for the GOP nomination. “He's not really running as a challenger to Trump,” she says. “He's running as somebody who's trying to elevate his brand, elevate his name ID, and simply become a player in politics.”

Ramaswamy insists he’s in it to win it, and would not even consider a role in a second Trump administration. The entrepreneur, who claims to be a billionaire, has already loaned his campaign $15 million and says he’s prepared to shell out an “unlimited” amount. When he walks onto the debate stage in Milwaukee on Aug. 23, he and his team expect they will capitalize on the momentum he's gained over six months of relentless campaigning. After that, Ramaswamy has plans for the campaign to shift to a more traditional strategy, with TV ads and more conventional means of voter contact. By the time the Iowa caucuses roll around in January, Ramaswamy believes he will have shown the Republican electorate what a viable Trump successor looks like.

For now, the frenetic approach continues. In the car in New Hampshire, Ramaswamy reserves the last 10 minutes of our ride to collect his thoughts and look at his phone. Peering at it, he finds something on social media that intrigues him. He plays an MSNBC clip of Al Sharpton commenting on Trump’s legal troubles. “Can you imagine our reading that James Madison or Thomas Jefferson tried to overthrow the government so they can stay in power?” Sharpton asks.

Ramaswamy chuckles. The glint in his eye suggests he knows he can work with this. “It’s very funny actually,” he begins, recalling how, back in his college days, he once asked Sharpton a question as a member of the audience during a news program. Ramaswamy can't remember what he asked back then. But now, as the car nears the next campaign stop in Concord, he tweets a response to Sharpton's remark: “It was called the American Revolution. We were successful. We won.” Before long, it will rack up more than 2 million views.

Earlier in the day, in Milford, several dozen people have crowded into a local grill. Some are willing to awkwardly eat their lunch standing up because something about this candidate in the crowded field has caught their interest. Ramaswamy may be the only one in the room of older, casually-attired voters wearing a suit. He spends thirteen minutes giving his stump speech and nearly another hour taking questions on everything from how he'll unify the country to his thoughts on modern monetary theory to what he would do to address pedophilia. Afterwards, he sticks around to meet with those waiting in a photo line that has formed.

Ramaswamy’s drive and charisma were apparent early on. Born in Cincinnati, his Indian immigrant parents’ search for the American Dream shaped his worldview. Coming to the U.S. without much money, his father became an engineer, his mother a psychiatrist. The values they taught him were more cultural than political, Ramaswamy tells me in the SUV. "That was sort of what we cared more about," he says, "Moral foundations."

During adolescence, he began to pick up a political education from outside influences, including a conservative Christian piano teacher who lauded Ronald Reagan. “She probably influenced me with modes of conservative thought that I probably wouldn't have thought about in the past,” Ramaswamy says. “Which were really the groundedness and importance of family, and sort of calling my attention to how blessed I was to grow up in a stable family environment like the one that I was in.”

Ramaswamy attended a majority Black middle school. He has said that another student pushed him down the stairs in eighth grade, requiring surgery. Afterwards, he transitioned to a Jesuit school, St. Xavier High School, where he stood out as one of the only Indian students in a mostly white class of boys. In his high school valedictorian speech, Ramaswamy recalled desperately looking around during mass freshman year, unsure of the words to songs and when to stand up and sit down. A sophomore religion class, he said, helped him learn about other perspectives and define his own. “I’ll definitely remember emerging from St. X with a personal faith that was neither Catholic nor strictly Hindu, but was finally something that I could call my own,” he told his fellow graduates.

Even as a teenager, Ramaswamy was known to be warm and sociable, able to chat about the Bengals and the Reds like anyone else. But the ways in which his background differed from his peers' was ever-present. It was only recently that his former business partner, Anson Frericks, who he met at St. Xavier, realized he had spent two decades mispronouncing his friend’s first name. (It rhymes with cake.) When another person brought the error to his attention, he confronted Ramaswamy.

“He's like, ‘Hey, you know, when you're the only Indian kid at an all-male Catholic high school, you just take whatever you're called,” Frericks says. (More recently, political insiders have questioned whether Ramaswamy’s standing in the polls has been hampered by many potential supporters in the overwhelmingly white Republican electorate having trouble giving pollsters his name.)

As an undergrad at Harvard, where he earned a biology degree, Ramaswamy crammed his calendar with extracurriculars: club tennis, the South Asian Association, the search committee for a new university president. He rapped under the pseudonym “Da Vek” and took on leadership roles in organizations like the Harvard Political Union and the Institute for Politics. He also joined the Harvard Republican Club. “I mostly, through college, considered myself a libertarian, a pretty staunch libertarian,” he tells me.

Ramaswamy was unafraid to speak out against campus liberalism. Nor did he shy away from disagreeing with his right-leaning friends on subjects like the treatment of prisoners at Guantanamo. In 2007, when then-FBI Director Robert Mueller visited campus, Ramaswamy grilled him about whether there should be an outside check on the FBI around civil liberties. “He just kind of said what he thought about different topics, even if it pissed people off,” says Paul Davis, a friend who was in the same dorm.

On a college trip to Las Vegas, Davis recalls, the two friends sat down at a blackjack table. The other player there, Davis says, was “a middle-aged white guy.” The dealer asked where Ramaswamy was from, and he replied that he was from Ohio. “[The dealer] says, ‘No, but where are you from originally?’” Davis recalls. “And Vivek said, ‘I was born in Cincinnati, Ohio.’ And the guy said, ‘But what's your nationality?’ And Vivek just replied, totally without a pause, ‘I'm a citizen of the greatest nation on Earth, the United States of America.’ … The other guy at the table thought that was a great answer.”

He may have sounded like a politician-in-training, but Ramaswamy’s focus at the time was the business world. While at Harvard, he co-founded Campus Venture Network, which sought to support student entrepreneurs, and was involved in launching a college consulting firm. After graduating in 2007, he joined QVT Financial LP, a hedge fund where he became a partner by age 28. Simultaneously, he attended Yale Law School.

It was around this time that Ramaswamy says he may have first had fleeting thoughts about someday running for office. "I considered it briefly, the idea of possibly doing it at some point, when I was in law school," he says. Some in his circle insist he didn't think much of electoral politics back then, but at least one person who knew him at that time tells me he mentioned plans to spend a decade building his business career before later becoming a candidate. The idea was to become so successful that he would be free to run on his true beliefs without bowing to the influence of the donor class.

Ramaswamy has said he was already a multi-millionaire by the time he earned his J.D. in 2013. The next year, he founded the drug development company Roivant Sciences, which sought to advance medicines that had stalled at other corporations. In 2015, through one of Roivant's subsidiaries, he pulled off the biggest initial public offering in U.S. biotech industry history at the time. The Alzheimer’s drug at the center of that IPO ultimately failed, but the company had other successes. Ramaswamy oversaw the development of several treatments that earned Food and Drug Administration approval, including a prostate cancer drug and one for overactive bladder. In 2016, he made Forbes’ list of richest entrepreneurs under 40. His fortune ballooned.

Then came 2020. After spending the previous year growing increasingly bothered by corporate pushes for ESG— environmental, social and governance investing—Ramaswamy authored an op-ed in the Wall Street Journal that argued business leaders should not be trying to shape America’s social and cultural values. The pandemic, and the racial-justice protests of that summer, only cemented his position. “He was frustrated," Frericks recalls. "His board of directors was asking him to take positions on controversial issues related to COVID policy or policy stemming from the death of George Floyd."

In 2021, Ramaswamy stepped down as Roivant CEO and published Woke, Inc., which became a New York Times bestseller. Soon he was a regular on Fox News. He and Frericks co-founded Strive, an asset-management firm that purported to forgo political agendas and prioritize shareholder value above all else. He quickly wrote another book, this one critiquing victimhood mindsets and identity politics. As he booked hundreds of cable news appearances, he got calls to run for Senate in Ohio, he says, and considered doing so.

The race he ultimately chose may have come as a surprise.

On February 21, Ramaswamy announced he was running for president in a video posted on YouTube. It begins with typical political-ad imagery: a small-town church, a worker welding, an exuberant family playing with kids and a dog in a field. Then the tone shifts, with clips of Dr. Anthony Fauci, climate activist Greta Thunberg, and transgender swimmer Lia Thomas, as Ramaswamy in voiceover warns of the dangers of “COVIDism, climatism, and gender ideology.”

"We hunger to be part of something bigger than ourselves yet we cannot even answer the question of what it means to be an American," the voiceover says.

The day of the video’s release, Ramaswamy laid out his campaign themes on Tucker Carlson’s show, where he waxed poetic about core American values like meritocracy, self-governance, and free speech. He also suggested that the left has sown division, leading Americans to focus on their differences. “I hope you’ll come back often, ‘cause you are one of the great talkers we’ve ever had,” Carlson told him.

In the weeks that followed, Ramaswamy took a kitchen-sink approach to campaigning, talking with almost anyone who would listen, with no concern about detractors he might find himself facing. “He's definitely impressed me a lot,” says Peter Christopher, a New Hampshire business owner who stopped for Ramaswamy’s lunchtime event. “He has an understanding of our culture today that he's not afraid to share. And yet, the way he shares it is not in a way that other people have to be wrong.”

Apoorva Ramaswamy, the candidate's wife, says there’s nothing he enjoys more than talking to people, especially those he disagrees with. “He loves being challenged, being forced to hone his arguments and his thought processes,” says Apoorva, who met him in 2011 while he was attending Yale Law School. “That's like his favorite hobby. You know, obviously he also likes sports. He loves tennis and football and basketball. But this is a sport. This is as much of a hobby to him as anything else.”

Ramaswamy has now spent months criss-crossing the country talking to voters. Much of that has been at town halls in the early states, but he’s also made it a point to pop up in places Republican candidates rarely do, like a Black barbershop in Chicago, where he got his hair clipped while discussing undocumented immigrants. Such moments drew social media attention and helped him stand out in the crowded Republican field.

“A lot of these candidates are very afraid of talking to the press,” says Davis, the college friend who has stayed in touch with Ramaswamy throughout the campaign. “And they're very afraid of being caught with a gotcha question, and they're really worried about, ‘Oh, this outlet is biased, and they're going to spin it this way, or that way, whatever."

Davis compares his friend's approach to the presidential campaign that Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg ran in 2020 as the little-known mayor of South Bend, Indiana. "Go on everywhere and have confidence that you're going to be okay at telling your story no matter what the platform is," he says. "And yes, maybe in some instances, you're gonna get an unfair article written about you, or the video’s gonna be cut in some way that's unfavorable or whatever. Yes, that's a risk you have to take, but it's actually a worthwhile risk to take."

Since April, Ramaswamy has found time to produce more than 50 episodes of a podcast where he hosts long-form conversations with people from across the political spectrum, from right-wing commentators like Glenn Beck to former Pennsylvania Governor Tom Wolf, a Democrat. The tapings are among the rare settings where Ramaswamy turns off his phone. A second season of The Vivek Show, for which he tells me he’s interviewed Papa John's founder John Schnatter and Libs of TikTok operator Chaya Raichik, is set to launch in early fall.

Ramaswamy's politics are often hard-right: he wants to cut federal regulators, supports ending affirmative action, and argues that trans kids are often dealing with unrelated mental health problems. But he doesn’t always sound like a typical Republican. Though he describes himself as personally “pro-life,” he is one of few GOP candidates who admits he does not support a federal abortion ban. He wants to ban social media for people under 16, and scrap the automatic right to vote for those under 25.

The first GOP presidential debate will be an opportunity to take his views to the largest audience yet. But according to Tricia McLaughlin, a senior advisor to Ramaswamy, the team sat down about a month ago and determined that doing traditional debate prep would require slowing down the hectic travel schedule that has helped connect him with voters around the country. Apart from some basic policy briefings, his campaign decided it wasn’t worth it. “All of our philosophy is ‘Let Vivek be Vivek’,” McLaughlin says.

Whether Trump appears at the debate may be the X factor. Ramaswamy has vociferously promised to pardon the former President, who, in turn, has responded by praising him effusively. Still, Trump has also reportedly told Ramaswamy that he may change his tune if his poll numbers start to approach Trump's own.

Ramaswamy is optimistic that that moment is not far off. “So far, we've had a 'talk to everyone approach,' purposefully a little bit unstructured, a little bit of intentional fluidity to the mechanics of how the campaign's been run," he tells me. "Following the launch of the first debate, I think we will be much more directed on the path to the early states and weave in more traditional campaign approaches.”

As the SUV pulls into an alley beside his next town-hall venue, Ramaswamy ruminates on how he stays in touch with regular people. He doesn’t spend lavishly on vacation homes, he says, but splashes out on private jets. “If we could buy time, we would take time,” he says. “Absolutely. That's the only thing private aviation buys us, is time.”

After we part, I search for that decades-old interaction with Sharpton that Ramaswamy had mentioned in the car. It isn’t hard to find. There he is on Hardball with Chris Matthews in 2003, an 18-year-old wearing a baby-blue button-down and a gleaming watch, hunched over a microphone to ask the first audience question of the evening. He notes that Senators John Kerry and John Edwards have already been on the show.

“Of all the Democratic candidates out there, why should I vote for the one with the least political experience?” the young Ramaswamy asks.

“Well, you shouldn’t, because I have the most political experience,” Sharpton replies, drawing cheers. “I got involved in the political movement when I was twelve years old. And I’ve been involved in social policy for the last 30 years, so don’t confuse people that have a job with political experience.”

Ramaswamy grins and nods along.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Mini Racker/New Hampshire at mini.racker@time.com