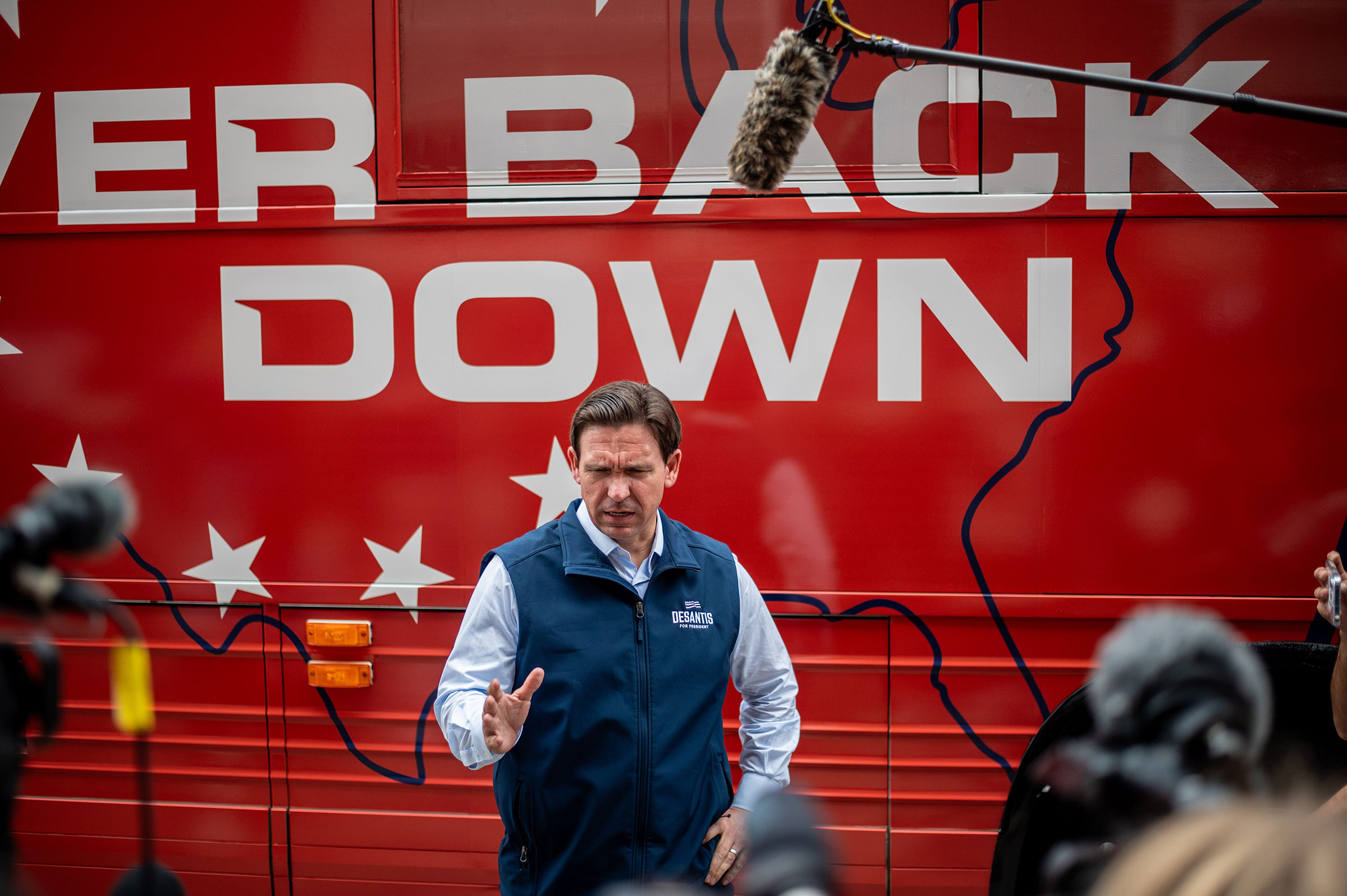

To hear Ron DeSantis tell it, his message hasn’t changed. “I think we were viewed, really from Day One, as the candidate that had the strong record on the issues important to parents,” he tells me, sitting at a table in a shaded pavilion on the sidelines of the Iowa State Fair. “It has been an issue, really, from the beginning,” he says of the “parents’ rights” agenda that has been central to his struggling presidential candidacy. “And so I do think we’ve tapped into that, and we’ll continue to do it.”

That may be the case, but something has clearly changed, starting with the fact that I’m interviewing DeSantis at all. For years, he has cast his opposition to the mainstream media in ideological terms, arguing that conservatives shouldn’t contribute to its legitimacy and shutting out any outlet this side of Fox News. But now, as he struggles to gain traction in the Republican primary against former President Donald Trump, DeSantis wants to talk to me about why he believes being the “parents’ candidate” will boost his political prospects.

As governor of Florida, DeSantis says, education policy is part of his purview, but it’s also personal. “I also just see it through the lens of a dad of a six, five and three-year-old,” he says, before switching to his usual first-person-plural. “We understand some of the things that parents are concerned about and that parents are going through. And that impacts how we view these policies, particularly when it goes to things like parents’ rights to be involved in the education.” On issues like school choice and curriculum transparency, he says, “in Florida, it’s not just Republican parents that care about that. A lot of independents and some Democrats were really appreciative of some of the stands we’ve taken.”

A few yards away from where we sit on wooden folding chairs, DeSantis’s wife Casey comforts their son Mason, 5, who is “having a morning” and feeling out of sorts. Later in the day, the two girls, 6-year-old Madison and 3-year-old Mamie, will join them, and the family will spend hours traipsing through the fairgrounds—going on rides, playing games—a show of wholesome, typical family behavior that's clearly aimed at showing the softer side of an introverted candidate often derided as wooden. The campaign's hope is to humanize the policy-focused DeSantis by linking his record to his personal life.

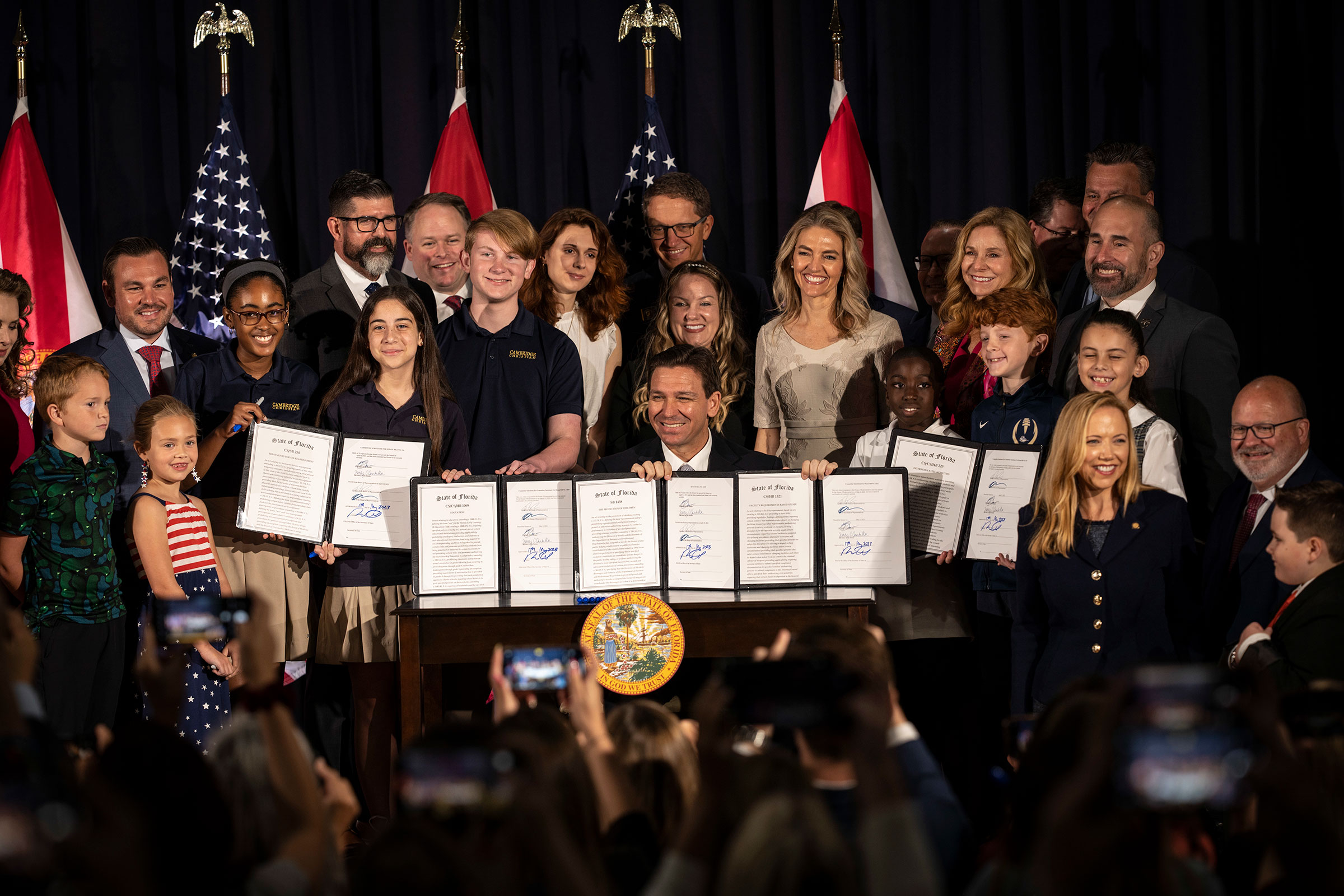

That record is hardly uncontroversial. Education and parental rights issues have been central to DeSantis’s agenda, which has departed from traditional Republican themes and emphasized hard-right culture wars. He pushed to open schools and opposed mask mandates in the fall of 2020; signed legislation, termed “don’t say gay” by critics, that banned the teaching of sex and gender before eighth grade, sparking an ongoing clash with Disney; barred transgender minors from accessing gender-affirming medical treatments, being called their preferred pronouns, or using their preferred bathrooms at school; crusaded against critical race theory, drafting new educational standards that have drawn criticism for their approach to slavery; mandated “curriculum transparency” that allows parents to challenge books used in classrooms, leading to restrictions that critics call book bans; and passed a sweeping school-choice law. All of these, in DeSantis’s view, are planks in a platform that adds up to protecting children’s innocence and safeguarding parents’ role as the primary decision-makers in their kids' education.

Read More: The DeSantis Project.

Framing it all as a crusade for "parents’ rights" is a neat trick politically, highlighting a throwback, traditionalist view of what used to be termed “family values,” but with a very 2023 culture-war spin. “Kids should be kids—there shouldn’t be an agenda,” he tells me. “I didn’t feel like there was an agenda when I was growing up.” It has the potential to remind voters of DeSantis’s aggressive policy record while highlighting his relative youth and vigor—an implicit contrast with the thrice-married, 77-year-old frontrunner, whose wife and eldest daughter have declined to campaign with him this time around. At the same time, skeptics point to DeSantis's slipping poll numbers and question whether all this resonates with an electorate polls show to be more concerned with kitchen-table issues.

As a father, DeSantis says, he’s not the primary disciplinarian in the family, but he’s capable of bringing the hammer down when needed. “I’m kind of the good guy most of the time—I bring the presents, I bring treats, especially when I’m on the road,” he tells me. “Day to day, Casey does more of the disciplining. But when I step in, and I do, if I’m a little stern, they snap into shape. I do that more rarely. But when things get out of hand, you kind of just lay the law down, and they respond to it. So I would say that they do respect the paternal influence.”

DeSantis sits wide-legged in jeans and a short-sleeved dark-blue fishing shirt with his name embroidered above both breast pockets, elbows planted on knees as he leans forward in his folding chair. He converses easily, albeit without deviating much from his standard talking points, and makes eye contact throughout our half-hour conversation. When I press him on whether he’s actually superseding parents’ rights with his own agenda, he argues that his school-choice law allows liberal parents to send their kids to private or charter schools that might take a different educational approach than he might prefer for his own children, as long as they meet basic standards.

I ask DeSantis about the rights of parents of trans children, who are being prevented by the state from accessing the medical care they may believe is in their kids’ best interest. He points to the ongoing debate over transgender treatment in Europe, where some experts have recently been moving away from a purely affirmative approach, arguing that the state has an interest in preventing “sterilizing children at age 13 or 14” or performing sex-change surgery on minors.

“As a parent right now, I can’t take my six-year-old daughter and get her a tattoo, even if I want to do that,” he says. “You don’t have the right to do things that are going to be destructive to kids. I think that some of these parents are being told by physicians who are making a lot of money off this that you have to do this, otherwise your kid can end up doing something like commit suicide. I think that they get bullied into thinking this is the right decision.” It is, he adds, “totally appropriate for us to say that protection of children means that those things are not appropriate.”

DeSantis’s attempt to personalize these issues has limits. When I ask how he was parented, he talks about where his parents were from—Youngstown, Ohio, and Aliquippa, Penn.—but says nothing about them as people. When I ask whether his view of the primacy of family comes from his faith, he responds in generalities rather than give a window into his personal spirituality. “My marriage and family, that’s just something that I always envisioned that would happen, and that’s been something that’s been very, very positive for me as a person,” he says. (DeSantis isn’t much for personal professions of devotion: “I know he’s Catholic, but I’m not even sure he attends Mass regularly,” the president of the Florida Family Policy Council, a DeSantis ally, told The Atlantic in March.)

And when I ask how he’ll respond if one of his children turns out to be gay or trans, his eyes flash momentarily, and he swiftly shuts down the question. “Well, my children are my children,” DeSantis says. “We'll leave that—we’ll leave that between my wife and I.”

After our interview, DeSantis heads to a stage behind JR’s SouthPork Ranch, where he is interviewed by Iowa’s Republican governor, Kim Reynolds, as part of her softball series of “fair-side chats” with the candidates. The beginning of the conversation is nearly drowned out by what appear to be liberal activists blowing whistles and banging cowbells. Ignoring Reynolds’s plea for “Iowa Nice,” a blue-haired activist in a black “Bitches Get Stuff Done” T-shirt is finally hauled away after an extensive argument with the police. All the while, a small plane hired by the Trump campaign circles overhead, dragging a banner with the message, “Be Likable, Ron!”

DeSantis emphasizes parents’ issues and his own parenting throughout the interview, talking about keeping the schools open during COVID-19 and not wanting his daughters to have to compete against boys in school sports. He tells numerous cute-kid stories, most of which feature the children being dragged along on campaign and official events, like the time Mason fell asleep at his feet at a press conference. He highlights Casey’s “Mamas for DeSantis” initiative, which she launched in Iowa at an event with Reynolds last month. “When you go after the kids, you’re awakening a sleeping giant,” he says.

Distractions aside, the audience appears receptive. “I thought he was powerful,” says Anne, 61, a physician from Ames who declines to give her last name but proclaims herself “excited” about DeSantis’s candidacy. “I like what he stands for. I like what he’s done for the state of Florida.” Anne tells me she previously voted for Trump but can no longer stomach him: “I’m kind of embarrassed by the stuff he’s been doing.”

Read More: Ron DeSantis's Latest Staff Shakeup Is Part of a Pattern.

DeSantis stops to answer questions from reporters, criticizing Trump for refusing to sign the Republican National Committee’s loyalty pledge and promise to support the GOP nominee. “It's not just about you,” he says. “You've got to be willing to stand up and support the team. And if someone's not willing to do that, that just shows you that they're running their campaigns more about them.”

The DeSantises proceed to the pork producers’ barn, where they gamely flip pork burgers. A cheer goes up as the governor flips the last one: the Trump plane has just been spotted flying overhead. A “We Love Trump” chant goes up from the former President’s supporters, many of whom are following DeSantis around in order to troll him, wearing green-and-yellow “Back to Back Iowa Champ” hats.

The family ignores the provocations and makes a show of partaking in the fair, a highly artificial endeavor that nonetheless makes for a good photo op and seems at least somewhat fun for the kids. DeSantis and his wife each walk the fairway with a tiny, bespectacled daughter on one hip. They ride the bumper cars (“Go easy on me!” Ron jokes to Casey) and the ferris wheel. They play fairway games involving popping water balloons and throwing baseballs into a milk can. They stop by the Magic Maze, where Mamie hesitates atop a hot-looking blue plastic spiral slide. “C’mon, you can do it!” her dad shouts from down below. As the entourage passes the Des Moines Register Political Soapbox, where DeSantis has declined to appear and take public questions, a rival GOP candidate, businessman Vivek Ramaswamy, can be heard declaiming, “God is real! There are two genders!”

As morning turns to afternoon, the atmosphere shifts. A crowd gathers around the Steer N' Stein, the open-air bar where Trump is scheduled to appear. The venue quickly fills up—screens inside advertise a $24-for-2024 “MAGA Meal Deal” consisting of a double cheeseburger, chili fries, and a 24-ounce soda, “Already Fixing Inflation!”—and a crowd at least 30 deep slowly expands around it. By the time Trump lands, the fair has virtually come to a standstill. Though the former President is in and out of the fair quickly, his status as the dominant force in the primary, the hub around which all things revolve, is affirmed.

DeSantis’s team has a tortoise-and-hare theory of the primary campaign. In our interview, the candidate waves off my questions about the much-hyped “reset” his operation has undergone, cutting a third of its staff and replacing the campaign manager. “We’re clicking, we’re going to be good,” he tells me. “I don’t think anyone in mid-January is going to look back and say, oh, you know, something that happened in June or July of the previous year is going to make much of a difference. All the stuff we need to do on the ground is being done in Iowa and New Hampshire.” In other settings DeSantis, a former Navy officer and the only veteran in the race, has described the reboot in military terms, casting it as a structural recalibration to better align the operation with the “commander’s intent.”

James Uthmeier, DeSantis’s newly appointed campaign manager, who previously served as his gubernatorial chief of staff and has never managed a political campaign, says the operation has beefed up its accessibility to media and hopes to deploy more surrogates going forward. “The governor’s got a great message, but people aren’t going to know about it if we don’t tell them,” he tells me. Over and over in Iowa and New Hampshire, Uthmeier says, he hears voters say they were planning to vote for Trump but changed their minds after hearing from DeSantis directly. “We’ve got the smartest guy in the room, somebody who actually studies the policy, knows it inside and out, and has ideas to succeed in executing that policy,” Uthmeier says. “It’s all about packaging that knowledge in a way that’s clear and concise and relatable to voters.” He likens DeSantis to a running back who waits for the right opening.

It’s impossible to tell, at this point in time, whether this stance is savvy and patient or the latest version of the deus-ex-machina delusion that has plagued the GOP for nearly a decade now—a conviction that somehow Trump will be removed from contention or collapse on his own accord. Despite its poor track record, the belief has gained new purchase in light of what are delicately referred to as Trump’s “legal challenges,” the four criminal indictments and 91 charges the former President now faces for everything from paying off a porn star to trying to overthrow the duly elected government.

DeSantis is a Harvard-educated lawyer who stresses law and order, and, at least when it comes to Dr. Anthony Fauci, the need for public officials to be held accountable. But when I ask about the indictments, he pivots to explaining why he would pardon Trump. “When I’m President, we need a fresh start,” he says. “Just like Ford pardoned Nixon, we are going to move on from the Trump controversies.” He goes on to argue that “the Department of Justice is highly political” and launches into an extended legal analysis of the Washington-based federal case brought by Special Counsel Jack Smith, which he calls “flimsy charges.”

“These are novel applications of the law, to conduct that has not traditionally been criminalized,” he says. “And I think that's why it's been viewed—at least in my judgment, and by people that think like me—very, very skeptically. Also, why all of a sudden are they doing this now? January 6 happened how many years ago, and I don't know what the agenda is behind that.”

DeSantis is hardly the only rival candidate to tiptoe around Trump, criticizing him on policy without condemning him outright. This forbearance has, of course, spared him none of Trump's wrath; Trump regularly accuses “DeSanctus” of having “no personality.” When I ask DeSantis to weigh in on Trump’s own personality, he dodges, turning instead to his familiar electability argument. “I must be doing something right to be able to have won a landslide re-election victory,” he boasts. “He was somebody that Biden beat him in that first debate in 2020 and beat him very soundly. I think that there are millions of voters out there who do not like Biden, do not like the direction of the country, but just will never vote for Donald Trump.” This argument, conveniently, is in the third person: the problem, as he describes it, isn’t that DeSantis dislikes Trump personally, but that others do.

“What we were able to do in Florida is a massive coalition,” DeSantis says. “Yes, we won Republicans big, I won Republicans by more than anyone has ever done. 97% of Republicans voted for me.” But he also, he notes, won independent voters and women voters. “And that's what we need, because clearly what we've done nationally recently is not enough to be able to get the job done,” he says. “I just think that the voters are begging for an alternative to Biden that they can get behind, and I would be that vessel.”

More From TIME

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Molly Ball at molly.ball@time.com