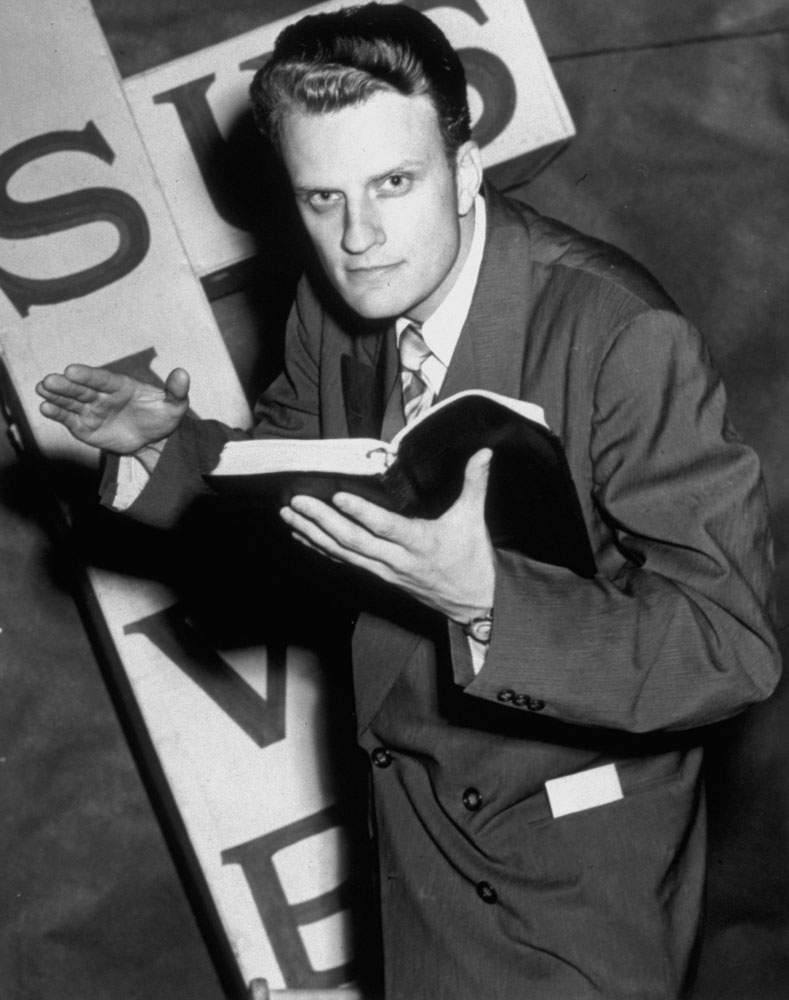

It is Billy Graham’s voice that will be missed most. The beguiling yet commanding North Carolina drawl, accompanied by the stab of a finger, itself as sure as God’s in the old paintings. “The Bible says …” Graham would announce, pointing to the book that seemed permanently attached to his other hand. And then he would tell us what it said and why it meant what it said and why we must give our lives over to it. The Word, Christians understand, is eternal; it just seems odd that that voice, which for decades seemed just as enduring, is gone.

Billy Graham died on Feb. 21 at age 99, and the hundreds of millions who love him have every reason to believe that he is now in a heaven he once, in his hyper-enthusiastic youth, described as follows: “We are going to sit around the fireplace and have parties, and the angels will wait on us, and we’ll drive down the golden streets in a yellow Cadillac convertible.” Yet his earthly legacy is everywhere. Ever read one of the Left Behind books? Notice all the so-called religion tests during the presidential primaries? Prayer breakfasts in Washington? Directly or indirectly, Graham was responsible for all these things. And, oh yes, the millions of people around the globe whom he brought to Christ.

William Franklin Graham Jr. was born on Nov. 7, 1918, in a frame house near Charlotte, N.C., into a family of reformed Presbyterians. He was, by his account, born again 16 years later. “I didn’t have any tears … There was no lightning,” he recalled. “I made my decision for Christ. It was as simple as that, and as conclusive.”

Graham became a Southern Baptist and briefly pastored a church, but his gift clearly lay in revivalism: as his wife Ruth later remarked, “I’d never heard anyone pray like that before.” Neither had newspaper tycoon William Randolph Hearst, who in 1949 cabled his editors a two-word directive to devote lots of space to the preacher then conducting a revival in Los Angeles: “Puff Graham.”

From there the hyperkinetic young man dubbed God’s Machine Gun moved on to triumphs from London to New York City, where in 1957 he preached for 16 weeks at Madison Square Garden, reaching more than 2 million people. His tent meetings became “crusades,” vast regional revivals that lasted for days at a time, drawing people from neighboring states and countries wherever Graham decided to put down stakes. Over six decades he preached in 185 countries and territories and as late as 2005 was attracting crowds of 242,000. With the possible exception of Pope John Paul II, Graham can be said to have touched more lives for Jesus than anyone else in the modern era and to have extolled him directly to a greater swath of humanity than anyone else in history. Referring to the original itinerant evangelist, Graham biographer William Martin notes wryly that “[the apostle] Paul was good for his time. But on numerous occasions Billy spoke to more people at once than Paul did in his entire lifetime.”

Graham did not reinvent revivalism, but like Henry Ford, he rationalized the production process. He supplemented his extraordinary charisma with meticulous advance work, military-grade organization and, eventually, every available technology from radio to television to global satellite transmissions to books and a magazine as well as, eventually, the Internet. He also established standards of financial and sexual propriety that maintained his reputation over a half-century of possible temptations and served as a model to shell-shocked colleagues after the televangelical scandals of the 1980s.

He never built the First Church of Billy or risked the temptations that came with that kind of brick-and-mortar legacy. He called himself a preacher, not a pastor, in part because he had no fixed congregation but mostly because spreading the Gospel was what he did best. Though his organization was vast — local crusades often took several years to plan, organize and produce — he traveled light, with just a handful of longtime aides and loyal sidemen, most notably the late George “How Great Thou Art” Beverly Shea, one of the great gospel singers of the past century. Graham’s stem-winding sermons, loaded with fire and brimstone in the ’40s and ’50s, cooled with the cultural revolts of the ’60s and ’70s, and by the time he launched his last crusade at Flushing Meadows–Corona Park in Queens, N.Y., in 2005, he was name-checking the Rolling Stones. But they all ended the same way, with the invitation — the gentle, forgiving call to come forward and accept Christ as your savior. Millions heard it and stepped forward. Homiletic success, in turn, enabled his great social achievement: the retrieval of conservative Christianity, kicking and screaming, from the American sidelines. “Without him,” says Randall Balmer, chair of the religion department at Dartmouth, “we’d be living in a different world … Evangelicalism today would have virtually no political or cultural relevance whatsoever.” Maintaining that “the one badge of Christian discipleship is not orthodoxy but love,” Graham eventually provoked a great evangelical schism — and his side won. Today a vanishing minority practices defensive isolationism, while Christian singles climb the mainstream music charts, theological hard-liners court — and find — millions of impressionable readers and conservative Christians can claim an important role in the world-wide fight against AIDS.

And that doesn’t even touch on politics. Graham pursued Presidents avidly, at the time an utterly bizarre evangelical interest. Harry S. Truman rebuffed him; Dwight D. Eisenhower welcomed him, accepted him and debriefed him after his foreign travels. Graham hobnobbed with John F. Kennedy and Bill Clinton but favored Republicans. But his coziest — and costliest — relationship was with Richard Nixon. Watergate not only left Graham personally disillusioned but also damaged his moral authority outside the evangelical world. The friendship haunted him again in 2002, with the release of an old White House tape on which Graham commiserated about the Jewish “stranglehold” on the media.

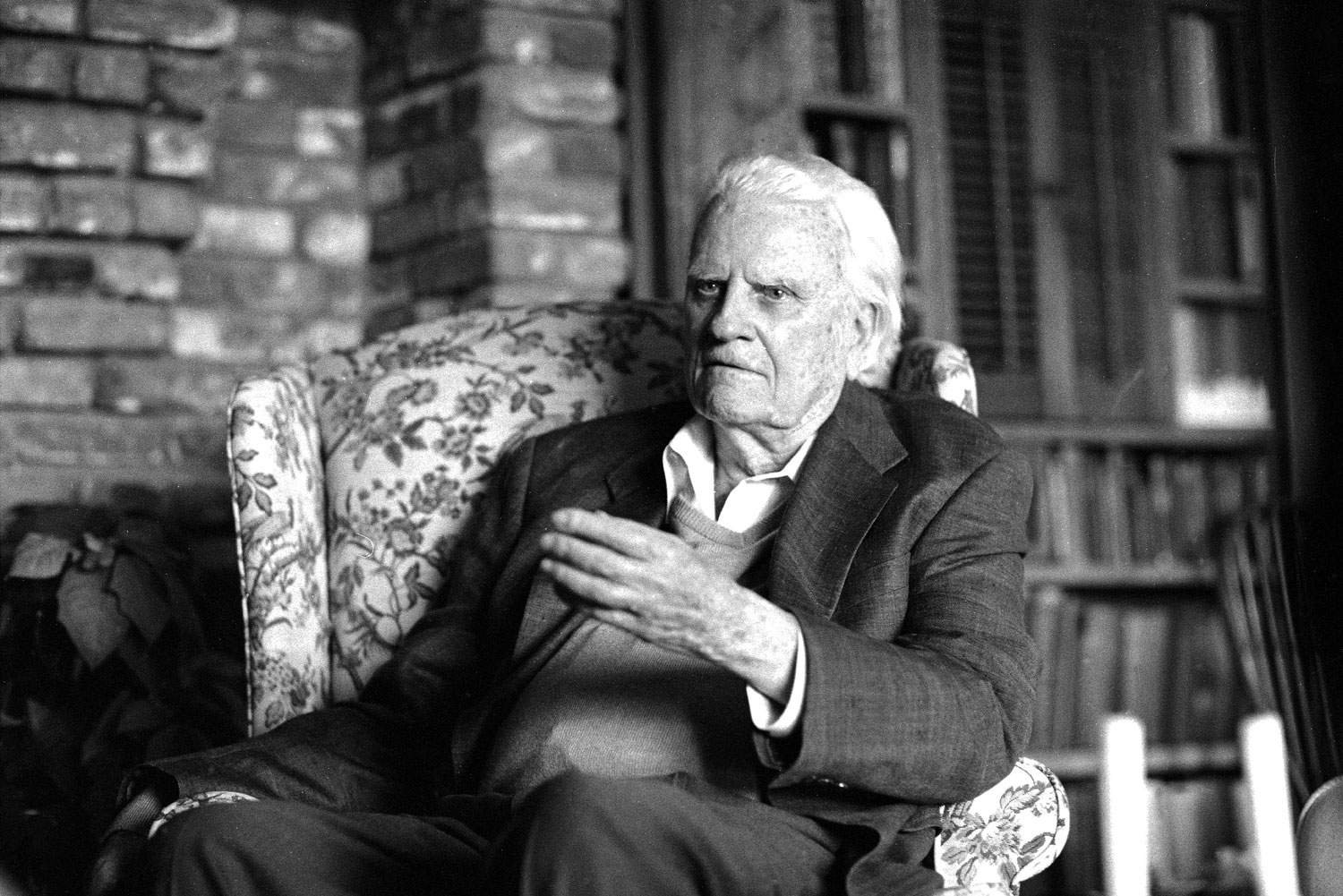

In his last years, Graham was increasingly incapacitated by Parkinson’s disease and eye trouble, yet both his past deeds and ongoing activities continued to resonate profoundly. It was his famous 1985 walk with the troubled son of yet another White House friend that helped lead George W. Bush to sobriety, conversion and his own political destiny. Offering the invocation at Bush’s first Inaugural was Billy’s son Franklin, the heir to his evangelical machine and an influential, if controversial, figure in his own right. (Another child, Anne Graham Lotz, is one of her generation’s foremost preachers.)

It is possible that Graham was unsettled by the renaissance he ushered in. Unlike his son, he rarely embraced the religious right’s legislative agenda, and by the late 1970s, notes biographer Martin, warned its standard bearers to “be wary of exercising political impact” to the detriment of their spiritual authority. But by and large, he could take satisfaction from a world more receptive to his own unadorned message of salvation than when he started.

Graham was modest about his achievements. “I don’t know why God has allowed me to have [all] this,” he told TIME in 1993. “I’ll have to ask him when I get to heaven.” But he must have guessed that He had recognized a unique servant when He saw one. Evangelicals are familiar with the story of Paul preaching on Mars Hill in Athens: some of his listeners scoffed; another group, well meaning, said, “We will hear you again about this.” Revivalists note that the latter remained unsaved, since the Bible tells us that “at that point, Paul left them.” Billy Graham was hardly the Gospel’s only late 20th century exponent, but he was easily the best. Those who meant to hear him but never got around to it have reason to rue his having gone out from among us.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com