The stars are out at this month’s FIFA Women’s World Cup in Australia and New Zealand.

By out, I mean out. Gone, too many of them. Not on rosters, felled by serious knee injuries.

Vivianne Miedema, the Netherlands’ all-time leading scorer. Delphine Cascarino and Marie-Antoinette Katoto, wizards of the French attack. Canada forward Janine Beckie of the reigning Olympic champions. Three starters on England, the top team in Europe. Zambia’s starting goalkeeper, Hazel Nali. Plus Catarina Macario, Mallory Swanson, Sam Mewis, and Christen Press, all marquee players for the two-time defending World Cup champion U.S. team.

More from TIME

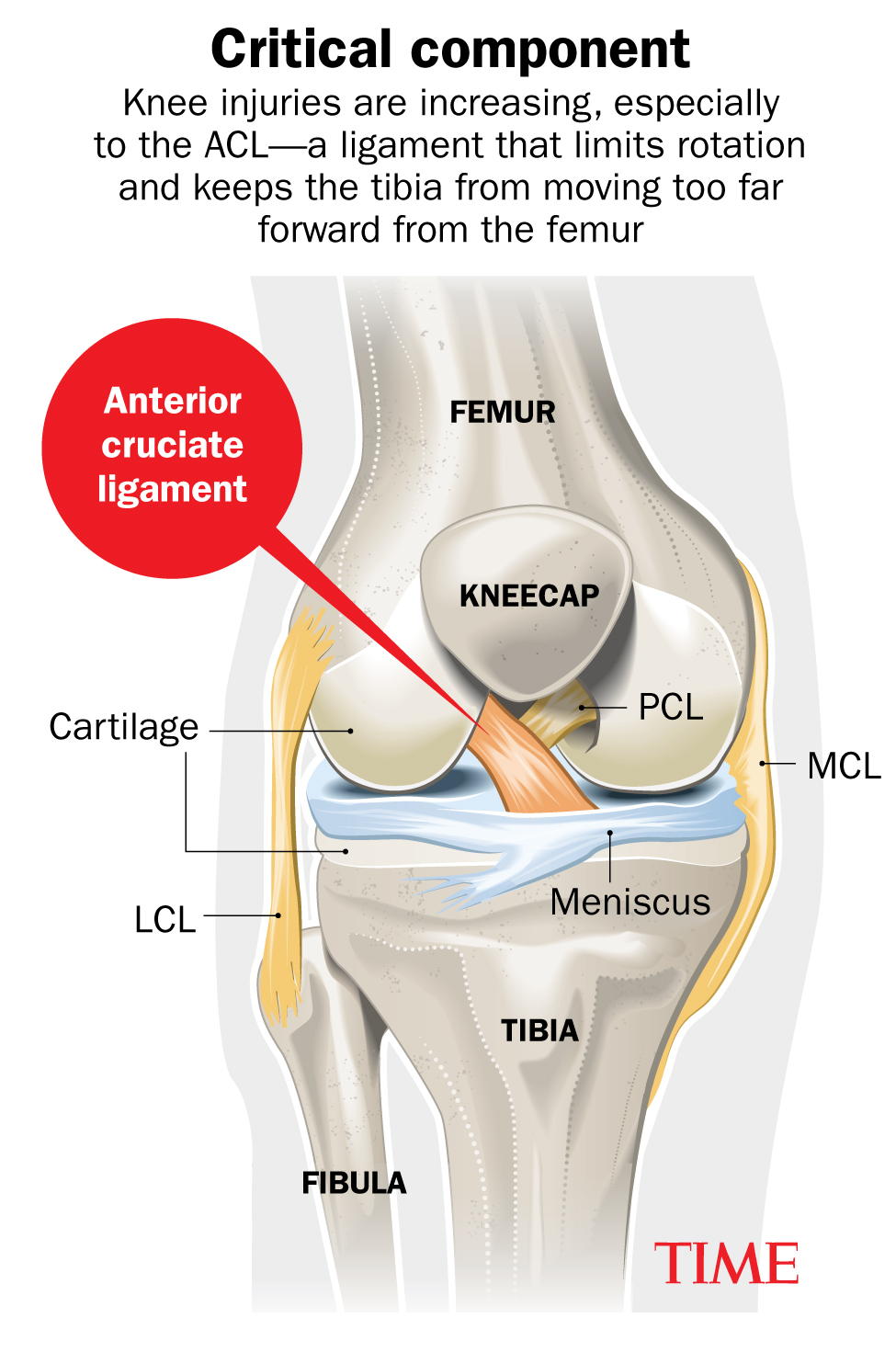

That’s a lot of highlight-making energy sucked from the sport’s biggest stage. And it’s just a glimpse of the horrors that have descended on the game broadly, largely due to ruptures of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), a thick, pinkie-finger-length tissue that runs through the center of the knee and helps connect the thigh bone to the shin bone. Internationally, at least 57 ACL injuries occurred among the six major women’s professional leagues since last year. The list includes five of the world’s top 20 players.

“It’s getting worse and worse,” said midfielder Kristie Mewis, Sam’s sister and one of at least six players with a prior ACL injury who made the U.S. roster. “The problem definitely needs to be addressed.”

It’s a nightmare at most levels of the game. NCAA teams have lost as many as six players in a year to ACL injuries. Many adolescent girls on club teams play nearly year-round, often under the supervision of coaches who lack training in injury prevention. Youth form the core of the 29-fold increase in ACL surgeries that doctors in the U.K. have seen over the past two decades.

Among soccer players of high school age, girls tear ACLs at three times the rate of boys for reasons that are not fully clear to doctors and could include hormonal or anatomical differences. But boys are suffering too. I have two sons. Both played soccer. Both blew their ACLs, my younger son three times on the same right knee. All were non-contact injuries, most of which are preventable with proper warm-ups that develop the necessary muscle strength and agility to cut and pivot safely.

My younger son is 19. Doctors tell him he probably should stay away from sports that require cutting maneuvers, like basketball, tennis, soccer, and volleyball, for life. That makes me sad, as someone who has enjoyed these sports my entire adult life.

As a sports parent, I didn’t become aware of the grim data until it was too late, and I wasn’t eager to share it with my son: Half of people who bust an ACL develop osteoarthritis within five to 15 years. He’s now seven times more likely to require a knee replacement. Total lifetime medical costs from the injury run from $38,000 to $88,000.

Read More: Meet the 14 Members of the U.S. Women’s Soccer Team Going to the World Cup for the First Time

Watching superstars like Jamal Murray, Alex Morgan, and Tom Brady recover and lead their teams to titles, it’s easy to assume ACL injuries are a solved problem. But these pros have access to the very best surgeons and rehab specialists; by contrast, youth-club medical directors are rare, and most high schools lack full-time athletic trainers. The responsibility of securing expensive physical therapy falls to parents.

Barely half of athletes return to competitive sport after ACL surgery, and only 81% play any sport again. Then there are the kids whose families lack the knowledge or health insurance to find a surgeon and pursue a proper recovery that will serve them into adulthood. This gap is another largely unexplored dimension to the ACL-injury crisis, the lack of health equity for athletes who, more often than students in wealthier communities, will move into blue-collar jobs that rely on regular use of their lower limbs.

Read More: What to Know About the U.S. Soccer Team in the 2023 Women’s World Cup

Knees are crucial for economic productivity and mental health. And they serve as extenders of life, given what we now know about the benefits of regular exercise.

Our society needs to start addressing knee injury with the same purpose as we have brain injury.

Over the past decade, sports organizations have introduced an array of new policies and practices in response to the danger of head injuries. The U.S. Soccer Federation delayed the introduction of heading in its youth programs. In football, state laws were enacted laws limiting the number of practice days that youth and school teams can go full contact. USA Hockey banned body checking in games before the age of 13 – and after Canada did the same concussions fell by 64%. The advocates and sport providers driving change have shown what’s possible.

Concussions remain more common than ACL injuries in high school sports. Still, the knee joint is the leading site of sport-related surgeries, with athletes in pivoting sports comprising the bulk of the more than 200,000 ACL injuries suffered annually in the U.S. And the recovery period is much longer – anywhere from seven to 18 months (compared to two weeks on average with concussion).

Each year, the New Jersey high school federation invites students to apply for an award recognizing their strength in returning from serious injury. This year, 27 of the 60 applicants relayed accounts of ACL injuries. Many of the stories are heartbreaking, and similar to what we hear with head injuries.

Read More: Megan Rapinoe Won’t Go Quietly

“Mentally, I was broken,” shared a female soccer player. “I thought there was no hope to get better. I had convinced myself that I just needed to accept that I may never play again, and if I did, it would never feel the same.”

Another wrote: “All I did all day was sleep. I could barely focus on the things I care about such as school, friends and family. I was in a very dark hole, and I couldn’t move out of it.”

So, how to attack this complex problem? In May, our Aspen Institute Sports & Society Program and Hospital for Special Surgery (HSS), the nation’s top-ranked orthopedic hospital, created the National ACL Injury Coalition, a group of experts and leaders that will work together through 2026 to identify and implement practices, partnerships, and resources that can reduce injuries in the high school population.

Step one: Get coaches to build better injury-prevention exercises into team activities. That includes neuro-muscular training, which develops muscle memory that optimizes athletic movement and leads to more control, agility, and strength during sudden changes of direction. Such exercises include squats and side lunges and can eliminate 50% to 80% of non-contact ACL injuries. As a side benefit, they improve athletic performance and reduce the risk of other injuries like ankle sprains and even concussions.

Team warm-ups should include the FIFA-developed protocol 11+. Or coaches could ask players to do these exercises at home and track their participation through an app.

“It’s there, it’s free,” said Dr. Andy Pearle, chief of sports medicine at HSS. “It’s seven minutes a day, four days a week. We just need coaches to implement it.”

Read More: How the Women’s World Cup Evolved Into What It Is Today

Coaches care about winning. So, let’s meet them where they are and start in sports with the highest rates of non-contact ACL injuries (soccer, football, basketball). Help coaches appreciate that they could lose their top athletes to this injury. Research by HSS shows that most adolescents have poor jumping mechanics, which increases their risk of planting, stopping, or landing in ways that damage the knee.

We need insurance companies to incentivize clubs and schools to adopt prevention tools. We need to empower athletes and parents to demand as much. And we need to address sport-governing-body policies that promote early sport specialization and travel tournaments with four games in a weekend, something professional athletes are never asked to play. Little League has pitch counts now to protect arms; since we know that players are injured more in games than practices, Pearle asks, why not save knees by adding annual “match counts” for vulnerable age groups in high-risk sports?

Sport and health leaders would be wise to get serious now. Soccer could heat up further in the run-up to the 2026 men’s World Cup co-hosted in the U.S., which is expected to be the biggest sporting event in history. Flag football is exploding in popularity with girls, which is great but also brings new knee risks given all the hard cuts.

The alternative? Do nothing and try to reform sports that will have doubled down on bad practice.

We’ve led the world on dealing with brain injuries. It’s time to do the same with knee injuries.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- How Far Trump Would Go

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- Saving Seconds Is Better Than Hours

- Why Your Breakfast Should Start with a Vegetable

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Ryan Gosling

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com