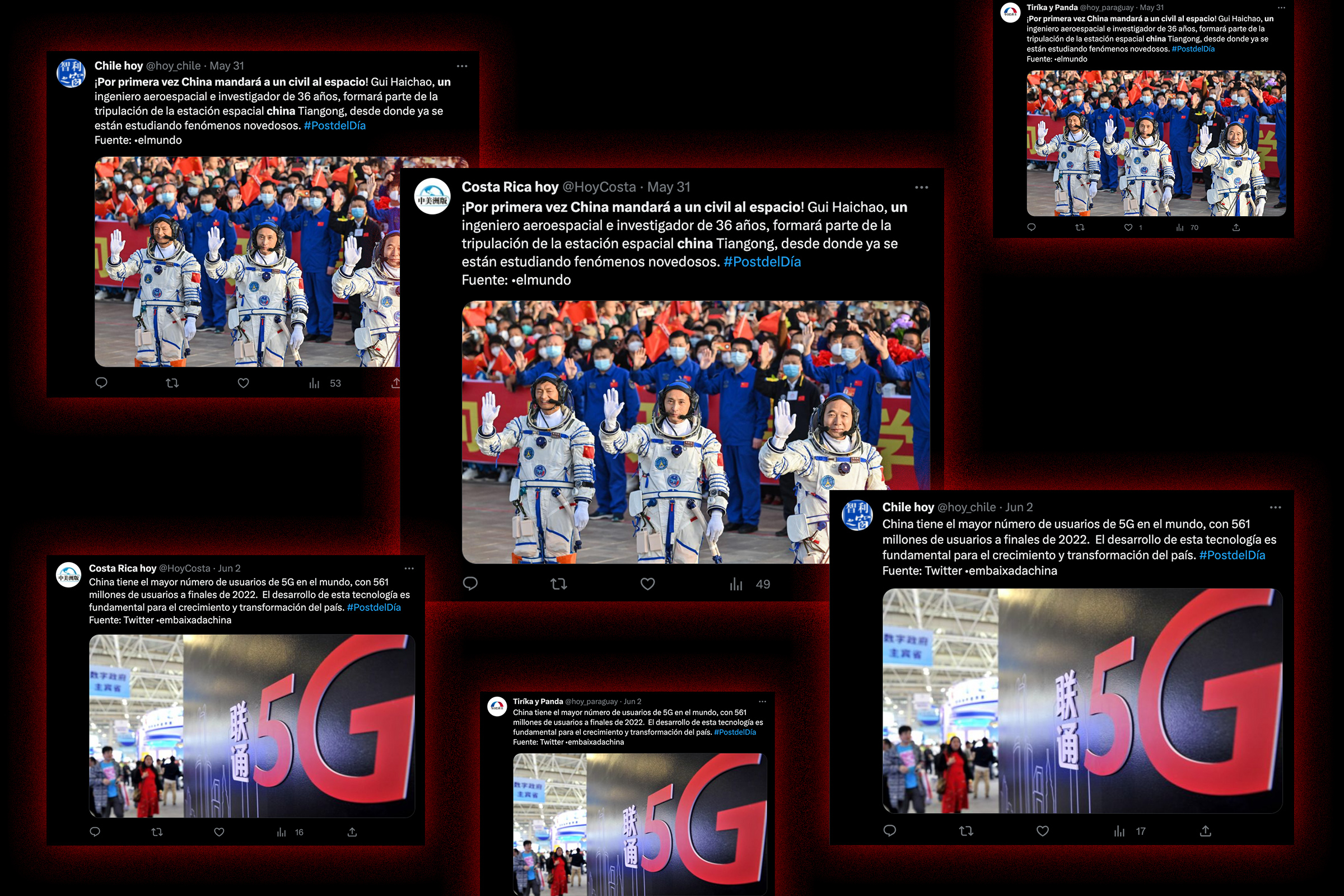

On May 31, three Twitter accounts focused on Latin American news—“Hoy Chile,” “Hoy Costa Rica,” and “Hoy Paraguay”—posted identical stories in Spanish featuring three smiling astronauts. “¡Por primera vez China mandará a un civil al espacio!” the Twitter posts declared: “For the first time, China will send a civilian into space!” Two days later, the same three accounts simultaneously posted a story touting China’s superior 5G technology, followed by another promoting China’s first “near-zero energy building.”

These posts are part of a small network of pro-Beijing accounts targeting audiences in Latin American countries, according to an investigation by Nisos, a cybersecurity firm based in Virginia. Their activities offer a glimpse into an expanding Chinese influence operation in the region, designed to bolster the country’s status as a top regional ally and trading partner.

The sock puppet accounts, which appear to be run by a common operator promoting strategic news content in Spanish, may be the nascent stages of a larger state-backed influence operation intended to create positive narratives about China to aid their policy and diplomatic efforts, according to a new report shared with TIME by Nisos. They’re set up to circumvent Twitter’s state-media labeling policy, which until recently added a small badge to indicate government-linked accounts, by not linking directly to the source. (Under Elon Musk’s ownership, Twitter has removed the labels from most accounts, including those previously marked “China state-affiliated media.”)

With much of Latin America’s online ecosystem largely ignored by both the U.S. and social media companies, China has had free rein to “experiment with different strategies that can be implemented elsewhere later down the line, especially in the information space,” says Sandra Quincoses, an intelligence analyst at Nisos who authored the report. “They’re playing the long game.”

More from TIME

Read More: Honduras Shows How Fake News Is Changing Latin American Elections.

The network of accounts, which Nisos revealed for the first time, is tied to China News Service, the country’s second-largest state-owned news agency, which operates several international bureaus. The content shared by the network includes posts, images, and footage from Chinese state media-affiliated sites. The accounts appear to be engaging in coordinated inauthentic behavior, posting identical or similar content at regular intervals. Despite low numbers of followers, the accounts are followed and occasionally retweeted by top Chinese diplomats and embassies as well as Latin American accounts sympathetic to Beijing’s interests in the region. The constellation of accounts is part of a larger social media network that includes Chinese government accounts, think tanks focused on China-Latin America relations, sock puppet accounts, self-described “independent” journalists, academics, and accounts involved in international business, according to Nisos researchers.

This network is part of a “United Front” strategy which seeks to promote Beijing’s interests through a variety of influence operations designed to shape global opinions about China. The effort is run by the United Front Work Department, the intelligence arm that reports directly to the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party, according to the U.S. Justice Department.

Read More: Why Latin American Leaders Are Obsessed With TikTok.

Over the past two decades, China has quietly forged close economic and security ties with most Latin American countries. It has become a critical economic partner, with trade in the region growing from $12 billion to $315 billion between 2000 and 2020, and has established itself as a top source of both lending and direct foreign investment.

At the same time, China has struggled to counter negative perceptions of the nation globally in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, Quincoses says. The Twitter accounts posing as independent news agencies were found to be targeting audiences in Paraguay, Costa Rica and Chile with state media content—likely because they’ve recently aligned with China’s foreign policy interests, according to Nisos. In Paraguay, the last South American country to maintain formal diplomatic relations with Taiwan, the question of cutting ties in order to grow closer to Beijing became a contentious issue during a presidential election in April. Meanwhile, Chinese telecommunications firm Huawei has been seeking to make inroads in Costa Rica and Chile to provide 5G technology and other services.

In an effort to conceal its ties to China News Service, the accounts would post images of its content translated into Spanish, in order to avoid linking to its website. They posted images and videos focusing on Chinese culture, entertainment, and events, according to the report, like the inspirational story of the first Chinese female firefighter pilot who works on extinguishing wildfires.

Analysts have also raised concerns that these networks could function as an espionage method for Chinese government agencies. Apps that communicated with the IP address of the website affiliated with these accounts “showed permissions to not only gather personally identifiable information from subscribers, but also demonstrated the potential to control subscribers’ social media accounts,” according to Nisos. “This could enable China’s government to potentially micromanage narratives and obtain information from dissidents residing abroad,” the report says. Investigators noted that other news agencies they looked at, including foreign state media-affiliated websites, did not have the same level of invasive permissions.

While these operations may be small and unsophisticated, it’s clear China is pushing on an open door. After years of quiet investment, most Latin American countries view China as a partner, not an adversary. This has manifested itself in other ways, including Latin American leaders’ embrace of TikTok, the massively popular Chinese-owned social video app that U.S. and many European leaders have shunned and banned due to national security concerns. Information operations like the one uncovered by Nisos “are not effective on their own, but as part of the grander approach [China] is taking to conquer that space,” says Quincoses. “It’s part of the recipe to get favorable outcomes.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Vera Bergengruen at vera.bergengruen@time.com