The moment the clock strikes 1:20 p.m., students are out of their seats and shoving laptops into backpacks, spilling out of the classroom and onto Stanford University’s lush California campus. But some stay behind, forming a line to speak to their guest lecturer. A few ask for selfies. Others talk about their workout routines. All look starstruck to be in the presence of Andrew Huberman, the man who has spent the last 80 minutes talking about neuroplasticity, memory, and learning.

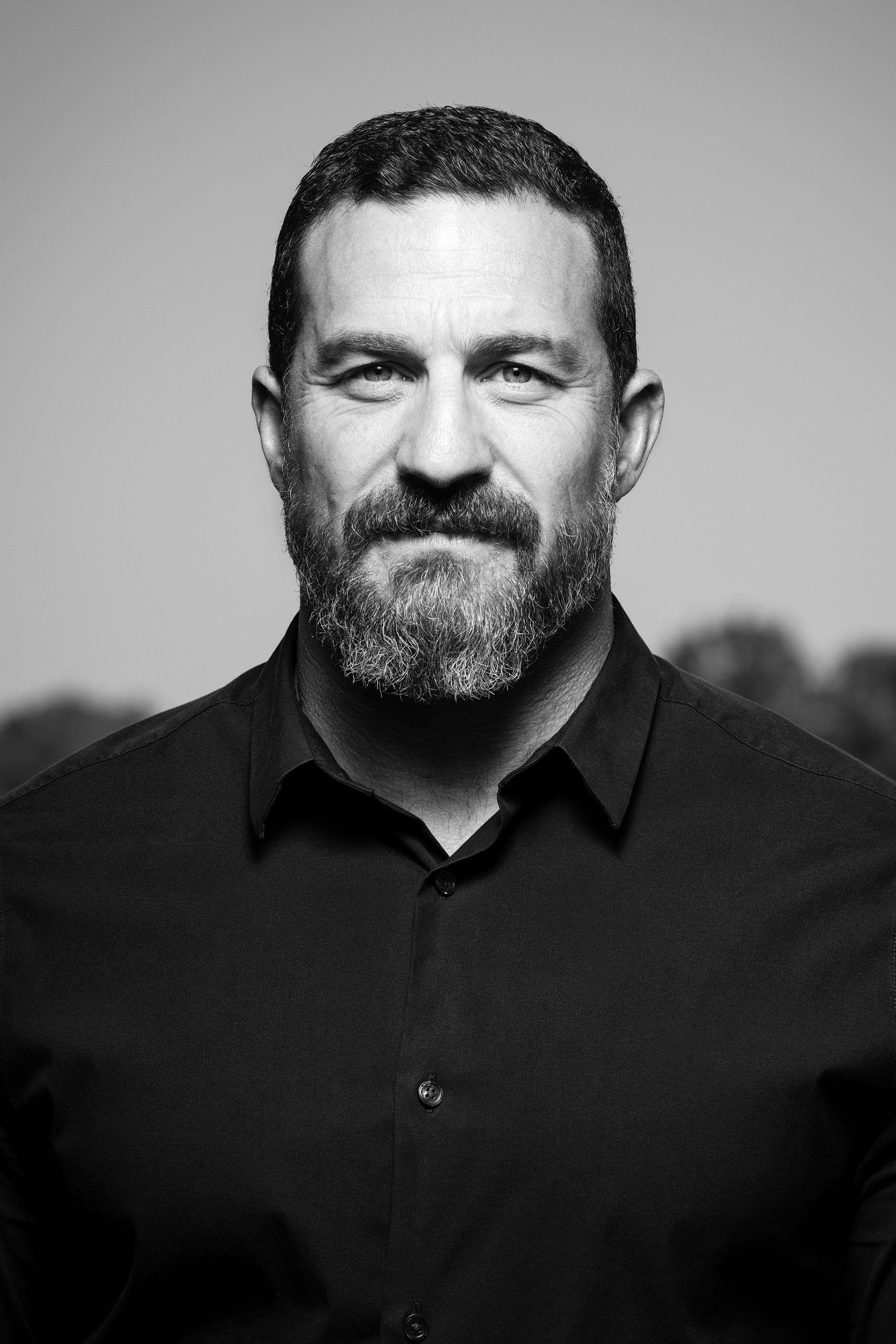

Arguably not since the Fauci mania of the early pandemic has a scientist become as famous, as quickly, as Huberman. The 47-year-old Stanford University neuroscientist hosts the Huberman Lab podcast, which consistently ranks among the top 10 podcasts on Spotify and Apple and has more than 3.5 million subscribers on YouTube. Since the show’s first episode in January 2021, Huberman has branched out into ticketed live shows, launched paid premium content for subscribers (with much of the net proceeds donated to scientific research projects), and signed a two-book contract with Simon & Schuster, the first of which is set to come out in 2024. Fans recognize him on the street, which isn’t entirely surprising considering that, in an effort to make his wardrobe simple and spill-proof, he almost always wears the same thing: a black button-down, black jeans, and black Adidas sneakers.

“He’s kind of a rock star in our field,” says David Berson, a neuroscientist at Brown University, who has known him since Huberman was a postdoctoral researcher and has appeared as a guest on his podcast.

Huberman is even intrigued by the thought of running for political office someday, though he has no immediate plans to do so. Politics seems like a slightly unnatural pursuit for a guy who won’t publicly discuss how he votes and doesn’t like meetings or being indoors, but Huberman does have certain relevant traits: He’s used to being in the public eye. He’s well-connected and well-educated. He has a fan base of millions—even if he still seems somewhat mystified by his role at the center of a growing media empire.

A long-form science podcast is not an obvious recipe for success at a time when attention spans are short, Americans’ trust in scientists is declining, and misinformation is rampant. And yet, Huberman has accumulated a massive and dedicated audience. At a sold-out live show in New York City in late 2022—where he talked for hours about everything from his childhood to brain science—finance bros in Patagonia vests sat shoulder-to-shoulder with elderly couples and parents out on the town with their adult kids.

Read More: 9 Podcasts That Were Turned Into TV Shows

The easy explanation for the Hubermania is that everyone likes to feel smart, and listening to a Stanford neuroscientist talk for hours about neurons and circadian rhythms and endogenous opioids scratches that itch. Huberman Lab also offers takeaways that people can use to improve—or “optimize,” in the vernacular of the show—their lives, an always-seductive promise when it comes to health and science. But Huberman has a more generous take, which is that most people genuinely want to learn. “I certainly believe people are most curious about themselves and the people close to them and why the world works the way it does,” he says.

He’s just happy to be the guy who explains it all.

More from TIME

I had a certain expectation of Huberman after listening to hours of his podcast and reading about his intimidating daily routine. Somehow, this guy finds time to put out regular episodes of a long and deeply researched podcast, lecture at an elite university, publish original research, exercise at an intense level, eat healthy meals, and get plenty of sleep. Is there any time left over for fun? I wondered. Is an optimized life really all that desirable? Huberman’s science-backed tips—or “protocols,” as he calls them—sounded rigid and joyless. I feared he’d be that way, too.

I was right about two things: Huberman is intense, and his definition of fun is likely different from the average person’s. (“I learn and I like to exercise,” he told me when I asked.) But he is not an optimization robot. Instead, he’s far more human and approachable than I gave him credit for—and he’s clear and open about the challenges that have shaped his life.

Huberman was born at Stanford Hospital, steps from where he is now a tenured professor and helms a neurobiology lab. As a little kid, his idea of a good time was reading the encyclopedia, then sharing what he’d learned with anyone who would listen. Around age 6, he started handing out dechlorination drops to people who won goldfish at local street fairs, knowing the fish would die if they weren’t kept in the right water.

Read More: Person of the Week: Elliot Page Steps Into His Truth

All signs were pointing toward a career in science until Huberman’s teenage years, when his parents divorced and he got involved in the Bay Area’s skateboarding scene. He found plenty of good in that world—kindness, music, a diversity of backgrounds and experiences—but also a roughness he’d never encountered before. “I saw a lot more drug use, a lot more alcohol use, a lot more physical violence,” Huberman tells me in a shady grove on the outskirts of Stanford’s campus.

Huberman stopped going to school during this “chaotic” phase and was eventually sent to a youth detention center. After about a month, he was released to finish high school. “I needed structure, and science and school provide structure,” Huberman says. He went on to earn his bachelor’s, master’s, and postdoctoral degrees through the University of California system and taught for a few years at the University of California, San Diego, before joining Stanford’s faculty in 2016.

For a while, Huberman was content to do his research and teach. Then, as 2018 turned to 2019, a friend asked what good he’d do for the world that year. Huberman decided to start posting science-education content on Instagram, which he barely used at the time. (He currently has 4.2 million followers on the platform, plus a million on Twitter.)

But I get the sense that it wasn’t just his friend’s question that drove him to seek a bigger platform. Huberman tells me about friends from the skateboarding world who overdosed and others who went to jail. He mentions that three of his academic mentors died prematurely—one by suicide and two from cancer. It’s clear that these losses affected him, and it doesn’t seem like a coincidence that a person surrounded by so much death has dedicated his life to helping others become healthier.

“After the third [mentor] died, I just said, ‘I have to tap into what got me into this whole thing in the first place,’” Huberman says, “which is a desire to learn and teach.”

Read More: The Best Podcasts of 2023 So Far

His initial posts took off, and in 2020 he became a frequent guest on podcasts—first small ones, then shows hosted by big names like Rich Roll and Joe Rogan. Eventually, encouraged by the artificial-intelligence researcher and podcaster Lex Fridman, Huberman decided to get into the game himself. He recorded the introduction to Huberman Lab’s first episode, titled “How Your Brain Works & Changes,” in a shower because it had good acoustics. In less than a year, he’d amassed about a million YouTube followers and solidified his place atop the podcast charts.

In each episode, Huberman dissects a single scientific topic in great detail, sometimes with the help of an expert guest but often on his own. Whether he’s tackling dopamine or strength training or alcohol consumption, Huberman delights in explaining how and why the brain and body do what they do. He’s good at breaking down dense scientific topics, but he also speaks like a human footnote, rattling off study citations, carefully contextualizing research findings, and doubling back to correct his wording or add more detail in real time.

This process takes a long time. Most Huberman Lab episodes clock in around two hours, but some stretch to three or four. Listening to a full episode can feel like an Olympic feat, both in terms of carving out the time and forcing oneself to focus for such a long stretch. (Ironically, Huberman often says the brain’s capacity for new learning fades after about 90 minutes of intense focus; he suggests listening in shorter chunks and admits he’s surprised that “people are willing to weather” the length of his episodes.)

Huberman decided from the start not to talk about COVID-19 or vaccines on the podcast, feeling there wasn’t much he could add to that discussion, but the pandemic was central to the show’s genesis. With the entire public-health community focused on avoiding the virus, he felt officials weren’t saying enough about how to stay well overall. Huberman was game to fill that void.

Along with old standbys like good sleep, nutrition, and exercise, Huberman’s favorite protocols include seeing direct sunlight as soon as possible after waking to help regulate circadian rhythms and improve energy and sleep; plunging into or showering in cold water to improve mood, energy, and focus; sweating in the sauna, which is linked to cardiovascular and other health benefits; delaying caffeine intake for a couple hours after waking to avoid an afternoon energy slump, if necessary; doing “physiological sighs,” a breathing pattern that rapidly busts stress; and practicing non-sleep deep rest, a relaxation technique that can restore energy and attention.

These practices make Huberman Lab appealing to the same audience that might listen to the popular podcasts hosted by productivity guru Tim Ferriss or longevity expert Dr. Peter Attia. (They’ve both appeared on Huberman’s show, and he on theirs.) Their content broadly falls under the umbrella of “biohacking,” or trying to improve physical and cognitive function through targeted lifestyle tweaks, from intermittent fasting to ice baths. Biohacking is a bona fide hobby for a certain kind of person—stereotypically, someone wealthy, male, and ambitious, though Huberman says his audience is split equally between men and women—and it’s become big business in the world of podcasting.

Huberman hates the word “biohacking,” because he thinks it implies people are taking shortcuts when they’re just harnessing science. But the protocols, not necessarily the lengthy discussions of scientific literature, appear to keep many listeners coming back to his podcast. In the 53,000-member-strong HubermanLab community on Reddit, posters frequently dissect how best to implement them. Devoted listeners summarize episodes for others, distilling Huberman’s lengthy monologues into practical nuggets of information.

Alex Badasci Lindmeier, a 45-year-old from Detroit, co-moderates the Reddit community along with his wife, Jenny Ip. The couple has incorporated many of Huberman’s protocols—morning sunlight, cold-water exposure, sauna sessions, and more—into their daily lives. The podcast even inspired them to build a cold-plunge pool in their backyard. For Lindmeier, Huberman’s appeal is his ability to “demystify very complex things” and “make the science more applicable and more useful for us.”

Despite the devoted fans, Huberman is not without his critics. He’s raised eyebrows for appearing on the shows of controversial podcasting personalities like Rogan, whose show sparked a Spotify boycott in 2022 after airing inflammatory comments about COVID-19 and vaccines. (Huberman says Rogan makes a sincere effort to promote public discussion of science, and adds that a guest appearance is not an endorsement.) In a June Instagram comment, Huberman also wrote that he was “eager to listen to” an episode of Rogan’s podcast featuring Robert F. Kennedy Jr., a 2024 presidential candidate and prolific spreader of anti-vaccine sentiment. (Huberman says he was praising a candidate’s willingness to appear on a long-form podcast and wants others to do the same.)

Huberman Lab’s content has also drawn criticism from some scientists who take issue with its approach. Science is a cautious field. Researchers are typically wary of overpromising, often softening their findings with words like “might” or “may” or “could” and calling for more research to be done before anyone gets too excited. While Huberman constantly adds context and caveats on the podcast, he also speaks with confidence about results he finds compelling. To some in the field, he translates preliminary research into lifestyle advice a little too liberally.

“He extrapolates [animal research] to things that we can do as humans, but those things aren’t really strongly supported for humans,” says Joseph Zundell, a cancer biologist who runs a science-education account on Instagram. And while Zundell trusts Huberman’s expertise in neuroscience, he feels Huberman sometimes strays too far from his training. Recent episodes have focused on topics including fertility, caffeine, and hair loss, for example. (Huberman says he and his producer decide together what to cover, then he does a deep dive into the research, interviews relevant experts, and sometimes invites one onto the podcast.)

Berson, the Brown neuroscientist, views Huberman’s podcast as “a fabulous service for the world,” a way to “open the doors” to the traditionally exclusive world of science and get the masses excited about learning. He says Huberman’s research is respected among fellow neuroscientists—but, he allows, Huberman’s decision to popularize and monetize his work, namely by accepting sponsorships for the podcast, isn’t universally condoned in the fairly conservative research community.

Perhaps most controversially, Huberman is not shy about talking about and running ads for dietary supplements. He says he’s taken the supplement AG1 (formerly known as Athletic Greens) since 2012; the company sponsored the very first episode of Huberman Lab and remains a sponsor today, along with several other supplement companies. This coziness with the supplement industry isn’t uncommon in the podcast world—numerous shows run ads for vitamins and supplements—but it has drawn flak from critics who feel Huberman is peddling products that aren’t carefully regulated or proven to be effective.

“The data on [supplements’] efficacy tends to come from small and often very short studies that have numerous limitations, but these preliminary results are served up as evidence by companies that want to make a quick buck,” says Jonathan Jarry, a science communicator with McGill University’s Office for Science and Society. “Someone like Professor Huberman should be aware of these things, but that does not appear to be the case.” (Studies have indeed shown that supplements offer limited benefits to most people, although some research is more favorable.)

Huberman agrees that supplements are “not absolutely necessary” and can’t replace foundations of good health like sleep, nutrition, and exercise, but he also says they can be beneficial when used alongside those things. He maintains there’s solid science to back up everything he talks about on the show, and that he makes it clear when he’s talking about preliminary research or single studies. He also routinely reminds listeners that he’s a professor, not a physician, and that he’s “professing” rather than prescribing.

As Huberman sees it, all he’s doing is giving people free access to the best, most current information he can find about their bodies and minds and a few science-based tools that might help them work better. Listeners can take or leave these tools as they see fit. He swears he’s a “live-and-let-live person” who won’t judge if you can’t stomach cold showers or don’t want to give up first-thing-in-the-morning coffee. He doesn’t even follow his own protocols 100% of the time. He loves pizza and croissants. He stays up too late sometimes (but mostly when he wants to keep reading or “foraging for information”). He sometimes binges Netflix, recently the action show Fauda. He reads the comments on YouTube. Every single moment isn’t optimized.

In fact, Huberman winces when I mention the word “optimization,” even though it’s one he uses frequently on the show. “Looking back, I probably wouldn’t use the word as often,” he says. “Optimization tends to rub people the wrong way. It implies, for some people, there’s a ‘best’ way and anything less than that or different than that is no good, and that certainly isn’t what we mean.”

He speaks with an earnestness that’s hard not to believe, even though, coming into our interview, I was nervous that Huberman would disapprove of my non-optimized lifestyle. It strikes me, too, that Huberman’s own version of optimization seems different from how we typically understand it, as an exercise in self-improvement. He seems to be thinking about how to maximize his time on earth in the service of others, even if he experiences some discomfort in the process. “I don’t know if this is good or not,” he says, “but more than I care about me, I care about the goal.”

The goal, as he describes it, has always been about teaching others, hopefully making their lives a little bit better in the process. The notoriety that has come from the pursuit of this goal is largely an accident, and not an entirely welcome one. Huberman visibly squirms when I call him famous, though he says he does enjoy meeting fans.

He seems to view a theoretical political run in a similar light: as a potential calling, but not necessarily a pleasant one. “It would have to be not about what I want,” he says. “It would have to be, my body is a vehicle to accomplish a very specific set of things that I feel I need to do and the world needs.”

When he says this, I’m reminded of the previous afternoon, when I’d sat in on his guest lecture for Stanford undergraduates. He confided in the group of students that, though he loved podcasting, his heart was really in the classroom, sharing knowledge face-to-face. That surprised me. Why do it all—the podcasts and the live shows and the book deals—if he’d rather be right back where he’d started, in the classroom and the lab?

“It’s a compulsion for me to learn and to teach,” he says when I ask if he ever thought about winding down Huberman Lab. The podcast allows him to do that on a larger scale than he ever could in a Stanford classroom, and he says he has no intention of stopping.

We talk a bit longer, but it’s been nearly three hours and Huberman has to start his journey back to Los Angeles, where he records the podcast and spends much of his time when he’s not on Stanford’s campus. He has a six-hour drive ahead of him and won’t be home until late, but he doesn’t mind. “I can think on the road,” he says—one last chance to optimize before the day comes to a close.

Correction, June 28

The original version of this story misstated the extent to which proceeds from Huberman Lab premium content are donated to scientific research. A portion of net proceeds are donated, not all net proceeds.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- L.A. Fires Show Reality of 1.5°C of Warming

- Home Losses From L.A. Fires Hasten ‘An Uninsurable Future’

- The Women Refusing to Participate in Trump’s Economy

- Bad Bunny On Heartbreak and New Album

- How to Dress Warmly for Cold Weather

- We’re Lucky to Have Been Alive in the Age of David Lynch

- The Motivational Trick That Makes You Exercise Harder

- Column: No One Won The War in Gaza

Write to Jamie Ducharme at jamie.ducharme@time.com