Rescuers are racing against time to locate five people onboard a commercial vessel that has gone missing in the Atlantic Ocean during an expedition to view the shipwreck of the Titanic.

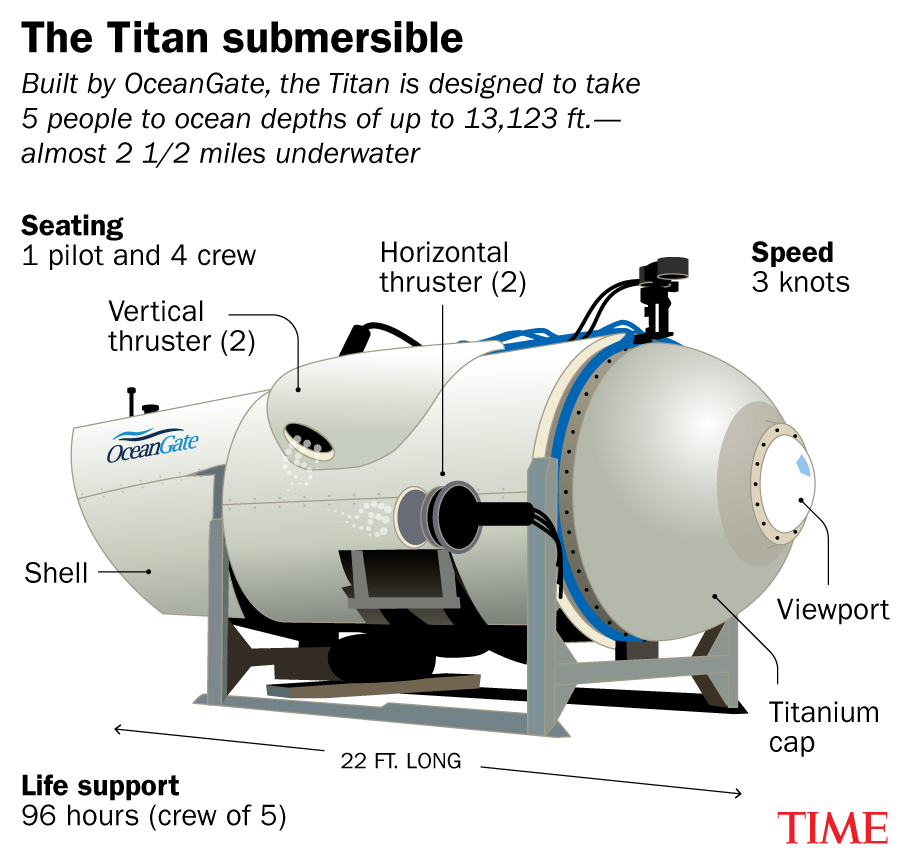

The Titan—a submersible belonging to U.S. company OceanGate—is a 22 ft.-long watercraft used for site survey and inspection, as well as research and data collection. The Titan lost contact about an hour and 45 minutes into the dive, according to the U.S. Coast Guard, and the breathable air supply on board is believed to be dwindling.

As the search continued through Tuesday, sonobuoys in the ocean picked up on banging sounds that could indicate the vessel’s whereabouts. “We don’t know the source of that noise, but we’ve shared that information with Navy experts to classify it,” U.S. Coast Guard First District Commander Rear Admiral John Mauger told CBS This Morning.

Read More: ‘Likely Signs of Life’ Detected During Search for Lost Titanic Tourist Vessel

Passengers onboard have been identified as Stockton Rush, chief executive officer and founder of OceanGate Inc., and Paul-Henry Nargeolet, nicknamed PH, who is a diver and Titanic researcher.

There were also three British citizens onboard: Shahzada Dawood, 48, a member of the Prince’s Trust charity’s global advisory board; his 19-year-old son Suleman; and Hamish Harding, a billionaire businessman. The company typically charges around $250,000 to take part in its explorations of the Titanic shipwreck, which sit 12,600 ft. below the ocean’s surface.

As the search continues for the missing submersible, here’s what to know about the watercraft.

What are submersibles?

Submersibles are small, limited range watercrafts designed for a set mission that are built to allow them to operate in a specific environment, according to maritime historian Salvatore Mercogliano. These vessels are typically able to be fully submerged into water and cruise using their own power supply and air renewal system.

While some submersibles are remotely-operated—essentially manually controlled or programmed robots—these usually operate unmanned. Vessels like the missing Titan are known as human-occupied vehicles. The Titan was designed to transport five people to depths of around 2.4 miles in order to reach the Titanic shipwreck. It weighs around 11.5 tons and can also take on speeds of about 3 knots, or 3.4 miles per hour.

“It doesn’t have a lot of propulsion so it can’t sail great distances but it has just enough propulsion to sail and operate in and around the wreck and then come back to the surface,” Mercogliano told TIME.

How are submersibles different from submarines?

The primary difference between a submersible and a submarine is that the former is launched from a mother vessel, or home vessel. “It doesn’t have things like typically large propulsion systems, it doesn’t have ballast systems,” Mercogliano says. “Basically, it’s like launching a boat from a ship—a submersible is very much nested.”

Unlike submarines, submersibles also have a viewport and external cameras to view the outside space surrounding the vessel. They also have limited power reserves, according to the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

How are submersibles safely retrieved?

Submersibles always operate in conjunction with a mother ship. They are typically launched on a raft or platform which is placed into water and ultimately descends down via four electric thrusters which help it to reach speeds of 3 knots. The vessel must remain in constant contact with the mother ship in order to coordinate a safe return. When it returns to the surface, it must be loaded back onto the surface platform.

Among other theories, experts believe that the Titan likely lost power or communication with its mother ship, the Polar Prince. Under this scenario, the Titan’s safety system would kick in, prompting the vessel to shed the weight it used to descend to the shipwreck.

Read more: See Photos of the Wreck of the Titanic When It Was First Discovered

“So in a scenario where Titan has lost communications, they dump their weights,” says Mercogliano. “They could be, for example, bobbing at the surface right now but the occupants cannot get out of that vessel because the Submersible is actually sealed from the outside.”

What are the safety regulations in place for submersibles?

Typically, marine operators must seek to have vessels “classed” by an independent body. The process would involve examining the vessel according to stringent standards and ensuring that the designs are safe. However, the Titan has not been classed in this way. OceanGate said in a blog post in 2019 that it did not seek to class the Titan because the process “does not address the operational risks.”

Instead, the company claims that “no other submersible currently utilizes real-time monitoring to monitor hull heath during a dive,” and therefore the integrity of the hull is guaranteed on each dive. It is also regarded as an experimental vessel that Mercogliano says is not bound to any particular regulations.

“Since this vessel doesn’t operate in coastal waters, it’s actually out in international waters, so there’s literally no rules and regulations that are governing it,” he says. In a 2019 profile interview for Smithsonian magazine, Rush, OceanGate’s CEO, said that there had been no injuries in the commercial submersible field for decades. “It’s obscenely safe because they have all these regulations. But it also hasn’t innovated or grown—because they have all these regulations,” he said.

But Mercogliano notes that any rules Rush may have been referring to would only apply if the vessel was in U.S. waters. “The submersible does not fly a flag, and it is not registered in any state or nation,” he said.

According to the New York Times, OceanGate was warned several times about potentially fatal outcomes of the expedition as early as January 2018, when experts became concerned about safety. The company’s own director of marine operations, David Lochridge, formulated a report that emphasized the “the potential dangers to passengers of the Titan as the submersible reached extreme depths.”

Additionally, as many as three dozen industry figures wrote a letter to Rush in March 2018, to voice their apprehension at the “experimental” approach OceanGate was using. The letter warned that the trip “could result in negative outcomes (from minor to catastrophic) that would have serious consequences for everyone in the industry.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Armani Syed at armani.syed@time.com