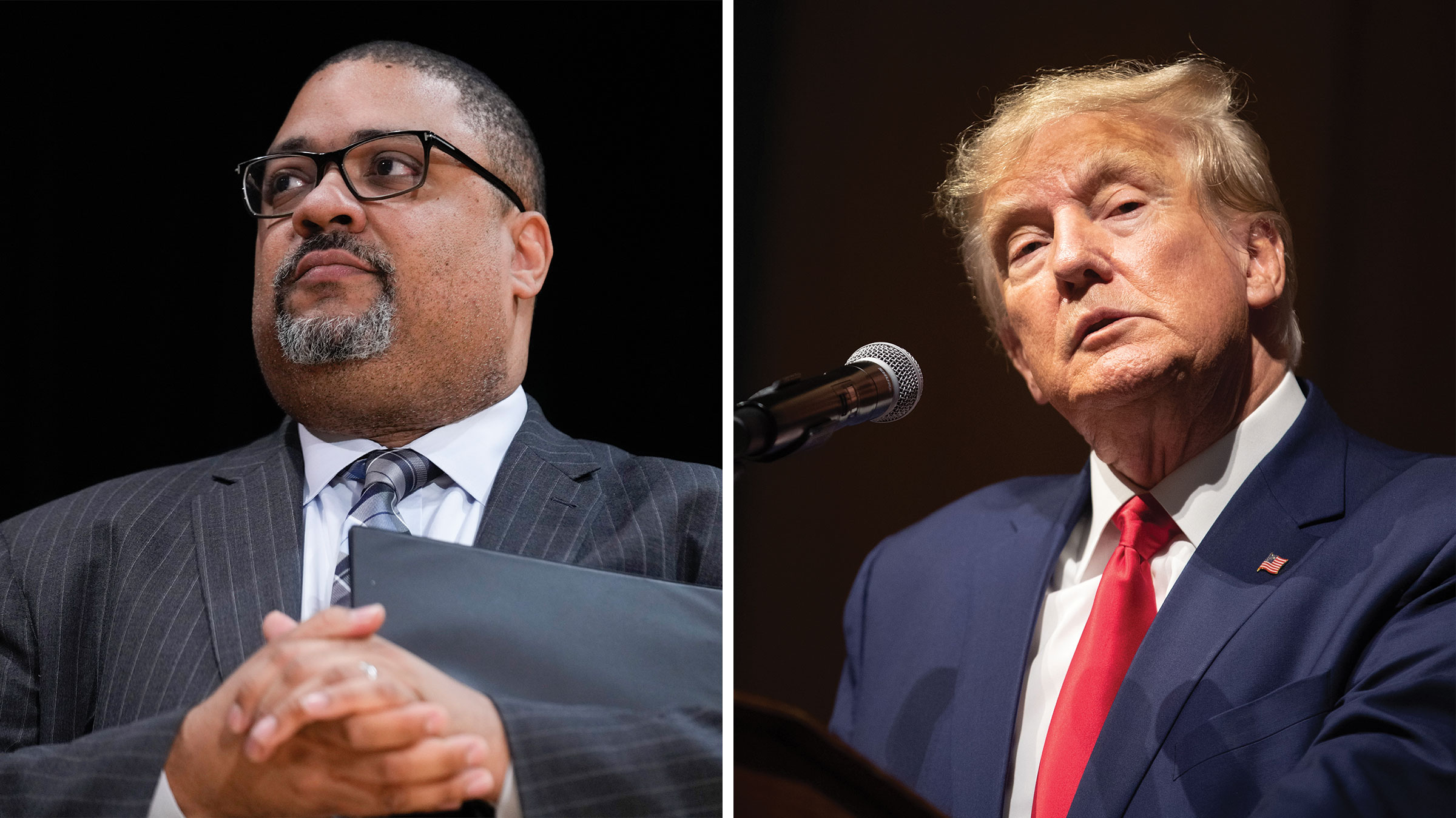

Alvin Bragg and Donald Trump are on the verge of an epic legal clash.

The Manhattan District Attorney is expected to indict the former President as soon as this week over falsifying financial records tied to alleged hush money payments to porn star Stormy Daniels during the 2016 campaign.

But while the looming courtroom showdown may be the first head-to-head collision between the two New Yorkers, it’s not the first time they have been on the opposite side of a combustible nationally-charged issue. Both men’s trajectories, in fact, were shaped in part by the same event more than 30 years ago: the Central Park Jogger Case.

The infamous case of the sexual assault of a 28-year-old investment banker jogging in Central Park had strikingly different impacts on Trump and Bragg, with the real estate mogul making one of his first forays into politics by calling for New York to resurrect the death penalty, and Bragg, a teen living not far from Central Park at the time, later pointing to the wrongful convictions of five Black and Latino men as a reason he chose to become a lawyer.

It’s a story that goes back to April 1989, when New York City was the epicenter of a historic country-wide crime wave, beset with more than 2,000 murders a year. Less than two weeks after the attack that made national headlines, Trump, who was a regular subject of intrigue in the local tabloids, took out full-page ads in four New York newspapers, including The New York Times, advocating for the return of capital punishment. “I want to hate these murderers and I always will,” Trump wrote in the May 1989 ad. “I am not looking to psychoanalyze or understand them, I am looking to punish them.”

Political pundits saw the move as strategic—an attempt by Trump to not only insinuate himself into local and national politics but to prop himself up as a foil to the city’s Democratic mayor, Ed Koch.

But for the five men who were wrongly convicted after being coerced into making false statements, the ads helped to intensify the growing bloodlust throughout the city. “He put a bounty on my head,” Korey Wise, who was imprisoned for more than a decade over the incident, told TIME in 2016. All of the men were later exonerated by DNA evidence in 2002.

None of that made an impression on Trump. In 2014, after New York City announced a $41 million settlement for the wrongly convicted, he wrote an op-ed calling the deal a “disgrace.”

“He’s a guy who’s never missed an opportunity to infuse himself into a public situation, if it meant that he would advance his plan,” David Kreizer, a lawyer who represented Wise in the 2014 settlement case, tells TIME. “We see that as far back as 1989. He used the money that he had to build that Trump brand, that Trump machine. It’s amazing foreshadowing that more than 30 years later, he’s still doing it.”

In 2019, while Trump was in the White House, a Netflix series on the incident “When They See Us” pushed it back into the national conversation. Trump continued to show no remorse for his behavior. “You have people on both sides of that,” Trump said, echoing comments he made about the 2017 neo-Nazi rally in Charlottesville. “They admitted their guilt.”

For Bragg, the case had the opposite effect. He was only 16 at the time, but the experience of watching it up close as a child of Manhattan was formative. “I grew up in the shadow of the Central Park Five case, which had an incredibly deep impact on me,” Bragg told The New York Amsterdam News in May 2022.

That was due in large part, he has said, because the incident had a personal resonance. “I was actually pulled over with some friends by the police not long after, who started interrogating us about a crime that we didn’t commit,” he told the Amsterdam News. “I was lucky—the reality of being a Black man meant I could have been one of the Exonerated Five.” In an interview with The American Prospect, in July 2021, he recounted enduring “three gunpoint stops by the NYPD during unconstitutional stops.”

After graduating from the prestigious Trinity School in Manhattan, Bragg went on to Harvard University and then Harvard Law School, where he was an editor for the Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review, a student-run progressive legal journal.

He then clerked for a federal judge before working at a private law firm on white collar crime and civil rights issues. Bragg soon left the private sector, first working for then-New York Attorney General Elliot Spitzer, and then becoming the chief of investigations for the New York City Council.

Those positions landed him on the radar of former New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman, who in 2017 appointed him as an Assistant Attorney General, where he ran the criminal justice and social justice units. In that role, he oversaw probes into the Trump Organizations, but those never led to an indictment. In 2019, he joined the race to replace Manhattan District Attorney Cyrus Vance, who wasn’t running for reelection. Ahead of the June 2021 Democratic primary, four of the Central Park Five endorsed Bragg in the race. He edged out his primary opponent and then cruised to victory over a Republican challenger in one of the bluest cities in America.

As the District Attorney, Bragg has shown the lasting imprint the Central Park Jogger case made on his psyche. He served as a co-defendant to exonerate one of the other defendants in the case, Steven Lopez. He also established a “Post-Conviction Justice Unit” that reviews and, in some cases, re-investigates old cases if there’s a possibility of a wrongful conviction.

“There are far too many people who have had their lives ruined due to unjust convictions,” Bragg said when announcing the division. “But beyond the impact it has on individuals and their families, unjust convictions undermine public safety by impairing law enforcement’s ability to apprehend those who actually committed the crime. They also severely undermine the public’s faith in our criminal justice system.”

When Bragg took over the DA’s office, it was already investigating allegations that Trump inflated the value of his assets to mislead and defraud lenders. Bragg ultimately decided not to press charges, a controversial decision in his office that led to a spate of resignations.

Now, however, he appears primed to go toe-to-toe with the former President who has famously escaped legal jeopardy for more than a half century, despite high levels of scrutiny from state and federal prosecutors. A man highly sensitive to the perils of a wrongful conviction is going to try to convict one of the most incendiary and difficult targets imaginable.

Two weeks ago, Bragg’s office invited Trump to testify before a grand jury, a move that former federal prosecutors and legal experts have said is a sign that his office was nearing an indictment. And then Trump himself wrote on his social media platform over the weekend that he was expecting to be arrested on Tuesday, calling for nationwide protests.

The arrest has not yet materialized, nor have protests of any substantial size. But an indictment does appear to be in the offing. If it happens, the case would mark the first ever criminal indictment of a current or former President. It promises to generate reams of controversy, not to mention grist for campaign attack ads in all directions.

Yet at the heart of the indictment are two native New Yorkers who, 34 years ago, watched the same event terrorize their city, and whose antithetical reactions helped to guide the rest of their professional lives. As fate would have it, they are now on the opposing sides of another historical moment.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com