The word Nan Goldin kept using to describe her presence at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, one night in February, for a screening of an Oscar-nominated documentary about her life and work, was surreal. It wasn’t that Goldin, a renowned photographer since the 1980s, was new to art-world accolades. But All the Beauty and the Bloodshed, a collaboration with Citizenfour director Laura Poitras, documents her crusade to get cultural institutions to cut ties with the Sackler family—the pharmaceutical dynasty that profited off America’s lethal opioid crisis. The film opens with a die-in that Goldin helped stage, in 2018, in the Met’s Sackler Wing.

Between then and now, the museum announced it would no longer accept donations from the Sacklers and excised their name from its galleries. Once the Met’s most cherished VIPs, they would now be persona non grata on the stage that welcomed Goldin. The same goes for the many other venerable cultural institutions, from the Guggenheim to the Tate to the Louvre, that Goldin and her activist group P.A.I.N. (Prescription Addiction Intervention Now) successfully pushed to end their association with the Sacklers, as Poitras’ cameras rolled. Beauty tells the unlikely story of an artist who has always aligned herself with marginalized, stigmatized, and disempowered communities risking her career to ruin the reputation of an obscenely privileged, hugely destructive family that spent billions laundering it. And she triumphs. As the film so elegantly demonstrates, in order to do so, Goldin has had to challenge some of our society’s most pernicious assumptions about what makes a person—or a name—respectable.

Beauty (which is now available for digital rental and will air March 19 on HBO) weaves together two apparently disparate portraits of Goldin. One traces the quest she embarked upon, while in recovery from her own addiction to OxyContin—which the Sacklers’ Purdue Pharma had aggressively marketed as a non-addictive wonder drug—to hold the family accountable. “To get their ear we will target their philanthropy,” the photographer wrote in an essay accompanying her Artforum portfolio announcing P.A.I.N. Where most celebrity advocates would be content to serve their cause through monetary contributions or media appearances, she throws herself into even the least glamorous aspects of activist work. Poitras observes P.A.I.N. meetings at Goldin’s home, where members hash out strategy and plan actions. En route to one demonstration, the artist applies labels to pill bottles that will be used as props. (“I love working in a material I know,” Goldin deadpans.) At another demonstration, we watch her get arrested.

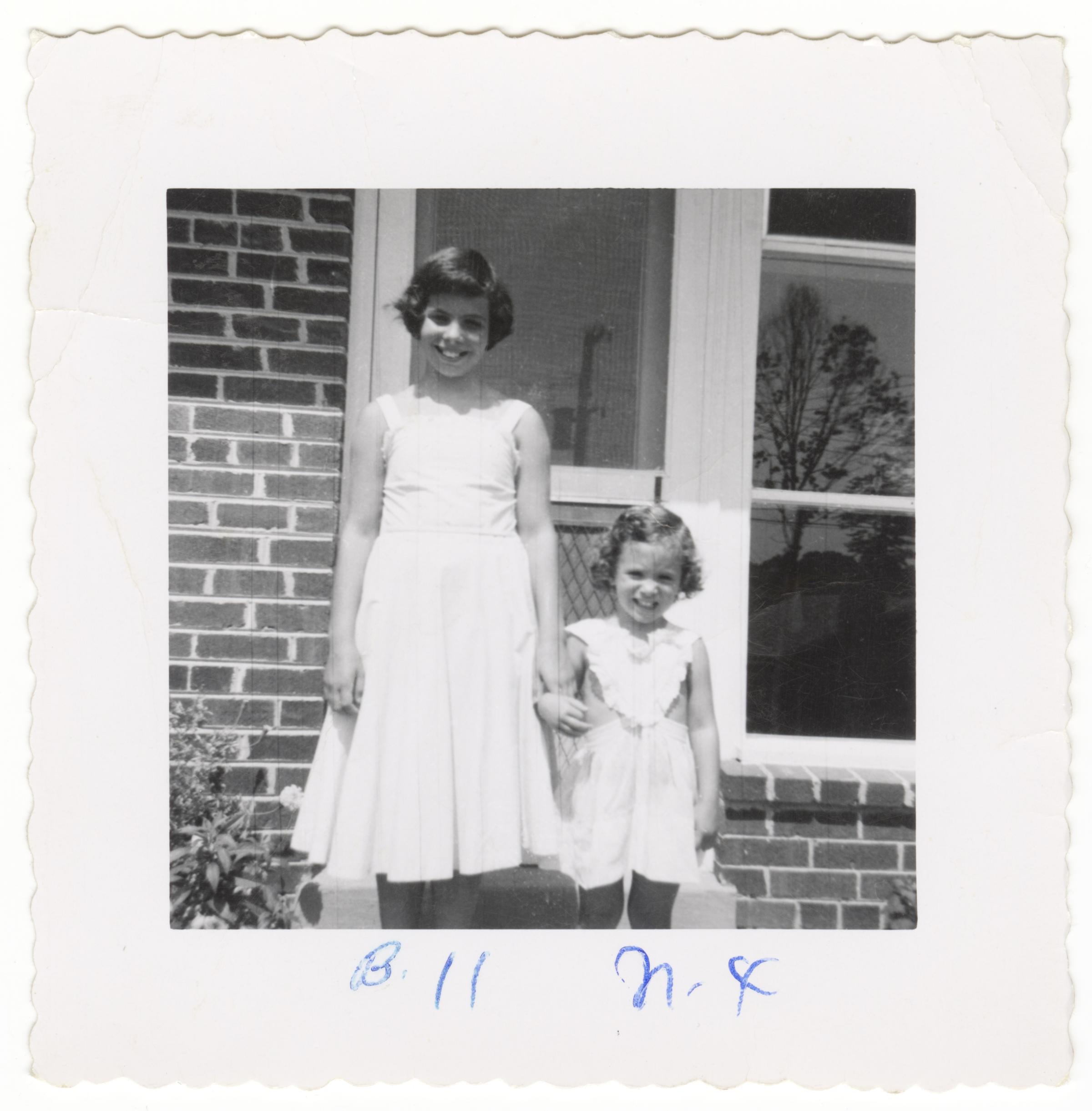

The other strand of Beauty is a chronological biography of the artist, interspersed with the striking images and slideshows that took her from downtown demimonde to international fame. Born in 1953 and raised in what she describes as “a claustrophobic suburb,” Goldin remembers her mother’s constant refrain: “Don’t let the neighbors know.” The secrets festering in her desperately unhappy—but outwardly normal—household led to the institutionalization and eventual suicide of her beloved older sister Barbara when Goldin was still in middle school. Nan ended up in the foster-care system, where one temporary mother straightened her hair, in what felt like an attempt to transform Goldin, who is Jewish, into a perfect WASP daughter.

Thus began a lifelong flight from the hypocritical and constraining circumstances of her childhood. Goldin finally landed at a “hippie free school that couldn’t throw me out,” which she remembers fondly. Shoplifting steaks at a grocery store as a teenager, she met her best friend, the late photographer David Armstrong. “We liberated each other,” she recalls. As the pair grew up, they became part of a queer, artistic community that faced constant threats of violence from so-called polite society but found sanctuary in nightlife. In ’70s Manhattan, Goldin immersed herself in the downtown art underground, which she would immortalize in warmly lit photos that captured the beauty of people (herself included) living at the margins: drag queens, sex workers, gay couples, abuse survivors. The AIDS crisis decimated her circle—Goldin’s dear friend, the writer and actor Cookie Mueller, died in 1989 at 40—and she responded by curating a provocative exhibition of art by HIV-positive contemporaries like David Wojnarowicz and Peter Hujar. Controversy ensued, and the NEA, which had underwritten the show, pulled its funding.

Poitras doesn’t need to hammer home the way this personal history shaped not only Goldin’s activism, but her worldview. That much is apparent from the way the filmmaker moves between her subject’s biography and artwork—most prominently Goldin’s masterpiece, the slideshow and perennial work in progress The Ballad of Sexual Dependency—and her David-and-Goliath campaign against the Sacklers. By the time she founded P.A.I.N., Goldin had spent decades watching relatively powerful avatars of the American mainstream demonize, if not destroy, anyone who attempted to escape their hegemony. From her pathologically square parents’ mistreatment of her rebellious sister to the friends she saw persecuted for the offense of existing while queer to the abuse she once suffered at the hands of a male partner, her life had been shaped by the unnecessary cruelty of people who considered themselves beacons of morality.

Freedom. Truth. Stigma. Reputation. Shame. These are the key words of Beauty, repeated again and again in a variety of contexts. Simply by sifting through Goldin’s past and present, Poitras raises questions like: Why should unfit parents have the authority to label their unconventional children broken? Why should a government whose homophobic neglect led directly to the deaths of millions of AIDS patients get to claim the moral high ground in silencing artists living with the virus when they express their anger at being left to die? And why should opioid addiction be shrouded in stigma and shame when the family that made a fortune peddling OxyContin strides proudly through art galleries and university buildings that bear its name?

It is Goldin’s courage and determination that make her an effective activist, and her empathetic eye that makes her a great artist. Another key word, community, captures the collaborative nature of P.A.I.N. and all the work she does, including this film. (“I didn’t do anything by myself,” Goldin noted at the Met screening.) But her radicalism, Poitras subtly argues, comes out of moral convictions that threaten the core beliefs of a conformist society that worships money and power—however they’re obtained—while vilifying vulnerability and difference. “Addiction is not a moral issue,” Goldin declares. Neither are sexual orientation or sex work or being born into a female body. Beauty insists on the urgency of talking openly and making art and organizing around these experiences, instead of bending to a regime that depends on their repression.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com