Heidi Leggett, a mother of five boys in southwest Virginia, has seen her family’s monthly spending on groceries increase from $2,200 to $3,000 in recent months. Like many across the U.S., her family is buying less and being more frugal with meals as prices of just about every food item have risen.

“We either have no leftovers or we plan a larger meal so we can eat leftovers for a few days,” says Leggett, who recently went back to work as a lobbyist to help her family deal with inflation. “Our quality of life has gone down. Worrying all of the time about what could be next is frightening. All we can think about is making our kids know that we will be OK and they will be taken care of.”

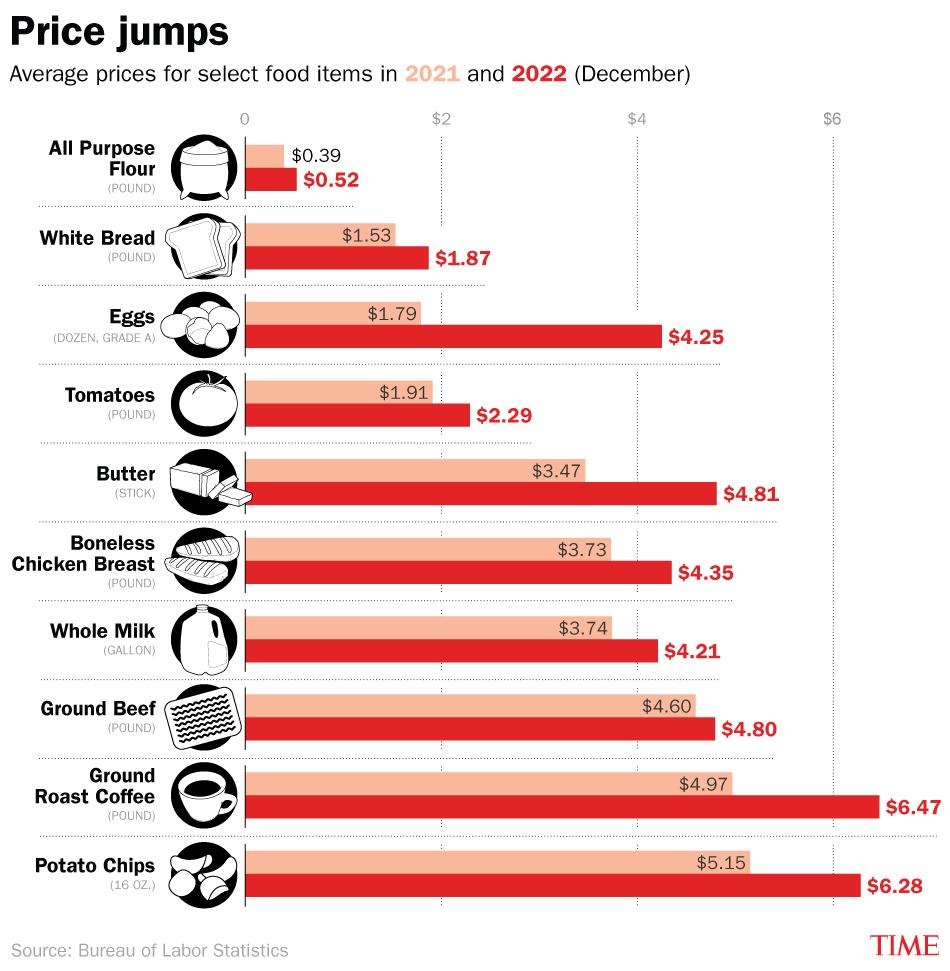

Although overall inflation is starting to cool, shoppers haven’t seen much relief in terms of grocery prices, which were up 11.8% in December compared with a year earlier. Gone are the days when someone could walk into a grocery store and buy a dozen eggs for $1.50 or a gallon of milk for under $3. Instead, nearly every food group costs more than it did a year ago: grade A eggs are up 138%; margarine, up 43.8%; butter sticks, up 38.5%; all-purpose flour, up 34.5%; and spaghetti and macaroni noodles up 31.3%, according to the most recent Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) data.

Many shoppers who TIME spoke with are struggling to keep up and asking when it will end.

Bridgette Moore, a 40-year-old mom of five from Lake Park, Ga., says she’s noticed that eating at fast food restaurants is now cheaper than purchasing healthy food from the store, even as she is more selective about her family’s needs and buys less items. “I haven’t had to work since 2009 and now with five kids, it is becoming more and more difficult to afford basic necessities,” she says. “It makes me feel upset and mad that my grocery bill has jumped over $200 per week. I didn’t expect to be in this situation, and it is a struggle to make ends meet.”

The stories these people shared painted a picture of the trade-offs and difficult decisions families across the nation are facing to afford everyday pantry items. For many, the frustration is starting to boil over.

“I am not happy with the state of the U.S. economy right now,” says Moore. “As a stay-at-home mom, I am worried about how I will provide for my family and it is difficult to see a way out. I hope that it will get better but with the current economic state, it is hard to say. We shouldn’t be struggling at this stage in life and we were not before.”

Analysts say that there’s no straight answer on when grocery prices will drop as it relies on a number of factors, including post-pandemic consumer demand, ongoing supply chain shortages, geopolitical events such as the war in Ukraine, and unstable weather patterns.

Read More: Best Credit Cards for Groceries 2023

But many of these key factors fueling inflation are starting to fade—meaning prices should stabilize this year, even if they may never go back down to pre-pandemic levels. Shipping costs are declining and Americans are purchasing less as they feel the pinch of inflation. Tom Bailey, senior analyst of consumer foods with Rabobank, predicts that prices will soften up in early 2023 as we “revert back to more improved production and more reasonable demand.”

Still, there’s a possibility that some prices continue to rise. “If the last 24 months have told us anything, don’t ever assume that things can’t change or get away from us,” he says.

Here is a guide to which food items are more expensive and why.

Chicken and eggs

A dozen grade A eggs cost, on average, $4.25 in December—making it the grocery staple with the largest year-over-year price increase. This is largely attributed to the ongoing avian bird flu epidemic, in which nearly 58 million birds have been infected as of January 6—the deadliest outbreak in U.S. history. Infected birds must be slaughtered, causing egg supplies to fall and prices to surge. The U.S. does not currently vaccinate chickens against the avian influenza virus, unlike Mexico and China.

“This is the largest animal emergency that USDA has ever faced in this country,” says Gino Lorenzoni, an assistant professor of poultry science and avian health at Penn State University. “And it doesn’t look like it’s going to stop anytime soon.”

But Farm Action, an advocacy group, believes there could be another reason for the high cost of eggs: price gouging. Cal-Maine Foods, which controls 20% of the retail egg market, reported quarterly sales up 110% and gross profits up more than 600% over the same quarter in the prior fiscal year, according to a December filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). The company pointed to decreased egg supply nationwide due to avian flu as the reason for higher prices and record sales, though Cal-Maine has had no positive avian flu tests on any of its farms, according to a quarterly report. Its brands include Egg-Land’s Best, Farmhouse Eggs, and Land O’ Lakes eggs. Cal-Maine did not respond to a request for comment.

“Avian flu is not manufactured—it’s real,” says Joe Maxwell, the co-founder of Farm Action. “But the dominant firms are using that supply chain disruption to gouge the consumers. The numbers in our letter [to the FTC] clearly indicate that the production loss due to avian flu was minor compared to the prices being charged.”

The egg market was even more inflated in December due to the popularity of holiday baking, when egg demand typically rises. But Bailey with Rabobank says that prices should start to ease between January and March—at least until Easter egg hunts bring another spike in demand.

“We are seeing prices coming off, but that’s primarily because demand is easing,” Bailey says. “There are still risks on the supply side with birds migrating in January. The question is can we fix it?”

Chicken meat prices have also increased by 10.9% from the year prior as a result of the avian flu. Farmers have since tried to increase production, and USDA data shows certain cuts are seeing decreased prices.

After seeing the price of eggs rise to an all-time high in 2022, Leggett and her family decided to build a chicken coop in their backyard, where they raise four chickens and produce about 26 eggs per week. “The chicken experience is rewarding,” Leggett says, “especially [because of] the eggs.”

Butter and margarine

The cost of butter and margarine has also skyrocketed over the last year, making the humble kitchen staple less affordable. One pound of butter now costs $4.81 on average across U.S. cities, up more than 31% from a year earlier when it cost $3.47. Margarine prices are up a whopping 44% from a year ago.

Dairy farmers say extreme heat and smaller cow herds—the result of pandemic financial struggles—are the main reasons behind the price increase for butter. Higher energy and fertilizer costs are also impacting how much Americans are paying for butter.

But seasonal demand for butter is starting to cool down, according to Bailey. That could be good news for consumers. “We can confidently say we’re seeing a turn in terms of pricing for butter,” he says. “It looks like the worst is behind us for now.”

Margarine production has been impacted by supply chain issues and the ongoing Russian invasion of Ukraine, which has disrupted production of their main ingredients—vegetable oils like sunflower and soybean, says Bailey.

Meat

The hotdog—America’s favorite summer staple—has seen prices increase by 18.2% in the last year, as lunch meats have similarly gone up by 15.1%. Much of the elevated costs for these items has to do with increased pork prices, says David P. Anderson, a professor in the Department of Agricultural Economics at Texas A&M University.

In the U.S., pork profitability has decreased, leading to a lower supply and higher prices.

Items like lunch meats and frankfurters also have to undergo more processing and packaging than a typical pack of pork chops. “Those extra steps have costs involved that are higher than they used to be,” Anderson says. That’s due at least in part to rising wages and a shortage of labor.

Those factors have also caused general spikes in the costs to transport goods, which have increased prices for food overall.

The price of beef, on the other hand, has decreased over the past year by about 3% due to increased supply—but the reason isn’t necessarily good. Droughts last year forced farmers to sell their cows earlier than usual, which helped lower prices. “They’re [still] at a really high level—higher than a five year average,” Anderson says, “but beef is one of the items that is cheaper than it was a year ago.”

Vegetables and fresh fruit

Fresh fruits and vegetables have also seen price increases, though lettuce is undoubtedly the biggest culprit, increasing 24.9% in the last twelve months. Romaine lettuce costs just over 9% more than it did a year ago.

Dry weather conditions and an insect-borne virus have damaged crops in California’s Salinas Valley, where much of the country’s lettuce is grown in the winter months. Bailey said that a wholesale box of romaine, which would normally cost around $10 to $20, was being sold for nearly $90 in November and December. These prices, which are passed on to consumers, are now closer to $30 as rainy weather has swept the west coast recently.

“Prices for lettuce are getting better and they should continue to flow to consumers,” Bailey says. “But we’ll need several years in a row of this kind of rain to fully relieve it.”

Nearly every fruit also costs more than it did last year. A pint of fresh strawberries is up more than 25% since November 2021, while apples are up 6.6%, lemons 3.5%, navel oranges 2.6%, and bananas 1.0% since December 2021, according to BLS. Field grown tomatoes cost 16.9% more year-over-year and white potatoes are roughly 22% more expensive.

How to save on groceries

Shopping expert Trae Bodge suggests families be open to shopping at a variety of stores to meet their needs. Dollar General, for instance, may not be on your usual list for grocery needs, but as the corporation dips into offering fresh produce, Bodge says there may be better deals at certain locations.

Many of the budget tips she shared involved spending money wisely by using credit cards that offer additional cash back or membership reward points at restaurants and U.S. supermarkets, or visiting sites like CouponCabin to get discounts.

Limiting food waste is another key element to consider. “I think you just have to be smarter, sharper and not to overdo it with whatever [you] get,” says Janet Yndigoyen, a paralegal from Belleville, NJ and mother of three. “Now, I need to be sure that whatever I buy we eat so that we don’t lose it.”

In the past year, Yndigoyen has sought to decrease costs by making adjustments to the types of food purchased—opting for non-name brand goods, or buying frozen fruits instead of fresh ones—and buying non-perishable goods in bulk.

Brendan Hodge, a finance professional from Delaware, Ohio in an eight-person household, has managed to keep his family’s average weekly grocery spending relatively the same since February 2021 by shopping at discount supermarkets like Aldi and significantly scaling back on certain high-price goods. He tracks his weekly household expenses in Excel, including outside food and drink, gas costs, and groceries, which he shared with TIME.

“We cut egg consumption from 2-3 dozen a week—lots of teens making eggs for breakfast and baking—to about a dozen a week,” he says. “We shop around more: my 5-year-old’s favorite cereal is $2/box cheaper at Meijer than Kroger.” He says his family also shifted their meat consumption to pork loins as the cost of chicken breast and beef rose.

Rising food insecurity

While grocery inflation has forced many Americans to cut back, for tens of millions, putting enough food on the table is now out of reach. New York city employee Mamie Wallace, 60, relies on the Food Bank for New York City for a weekly prepared meal and supplemental grocery needs. She represents the one in 10 Americans living in a food-insecure household.

“The things that I used to buy, I can’t afford now,” says Wallace, who lives alone. “I didn’t notice [food inflation at first] because I had my freezer stocked up but since it’s been over a year now, things are starting to run out.”

Matthew Honeycutt, Chief Development Officer of the Food Bank for New York City says the food bank—like most Americans— has also had to make changes to address ongoing needs. In the last fiscal year, the pantry year has seen a 74% increase in their procurement of non-meat proteins because of high meat and poultry costs.

The food bank has also had to decrease the quantity of food patrons typically receive, which impacts those most in need. “Families end up going to more than one pantry to get enough food now whereas it used to be able to go to one and they could supply them with enough for a week,” Honeycutt says.

If you need help to supplement your grocery needs, you can visit Food Finder, which maps food pantry locations across the U.S. You can also find a local community garden by visiting the following link.

Seniors can also take advantage of programs like Meals on Wheels, while help serve nutritious meals to the elderly and provide wellness checks.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Write to Nik Popli at nik.popli@time.com