More than 30 years before he was elected to lead 211 of his fellow Democrats in Washington, Hakeem Jeffries was tapped to lead a dozen young men in upstate New York.

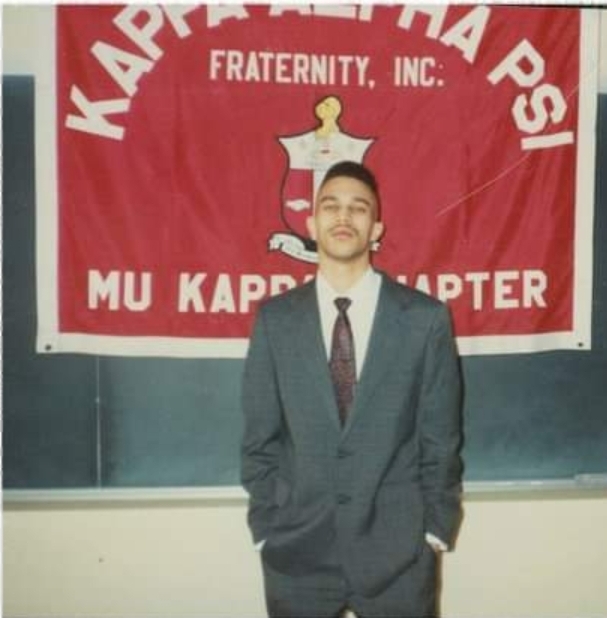

Jeffries was only a college sophomore at Binghamton University when he was elected president of the school’s fledgling chapter of Kappa Alpha Psi. He had joined the fraternity just a year earlier in search of community in his new home, nearly 200 miles and a world away from his Brooklyn upbringing. Jeffries has since credited his time in the historically Black fraternity as a defining era of his life.

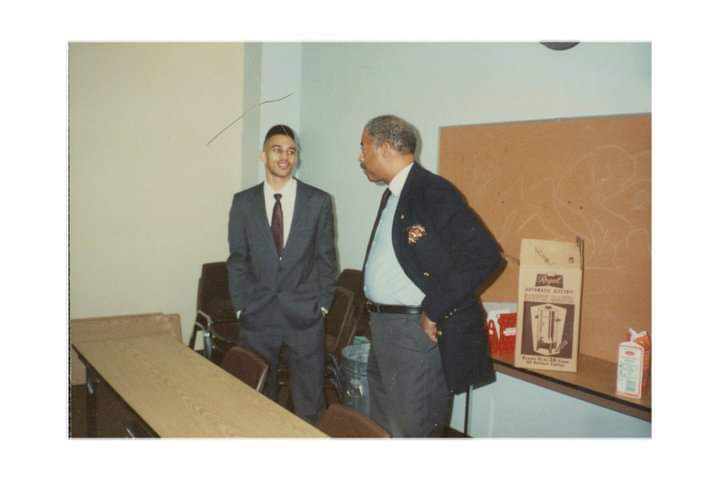

“He was a force to be reckoned with,” Joseph Cordero, who was two years ahead of Jeffries and a fellow “Nupe,” recalls of the man who would go on to be the first Black lawmaker to lead either party in Congress. Picking an underclassman like Jeffries to run the chapter fit with the Kappa Alpha Psi mantra of “training for leadership,” Cordero adds, by letting “the youngest brothers in the chapter run the chapter while the older ones can provide mentorship.”

That pattern is set to repeat this year, with Nancy Pelosi stepping down as House Speaker to make room at the top for Jeffries, while sticking around to help guide the 52-year-old as he manages the caucus.

He’ll also have some fraternity brothers to lean on for support. When Rep. Troy Carter of Louisiana got to Congress in 2021, he and Jeffries joked about how they would work on growing their ranks in Congress. Rep. Sanford Bishop of Georgia is a Kappa too, as is Rep. Bennie Thompson of Mississippi, who served as chairman of the groundbreaking Jan. 6 committee. Former members of Congress who were Kappas include Alcee Hastings of Florida, Don McEachin of Virginia, and Louis Stokes of Ohio, who helped lay the foundation of the Congressional Black Caucus.

“Many people think of fraternities as just, you know, beer bongs and parties and all that, and I guess there’s a time that that is a part of it,” says Carter. “As you mature, it’s so much more.”

Other Kappa Alpha Psi alumni include famed NBA center Wilt Chamberlain, civil rights activist and quarterback Colin Kaepernick, lawyer Johnnie Cochran, and New York Times columnist Charles Blow, as well as Mandela Barnes, the former Wisconsin lieutenant governor who nearly flipped a U.S. Senate seat last year.

For many of them, joining Kappa Alpha Psi represented a lifetime commitment to leadership and social change. “Most folks that I talk to who were members of white fraternities and sororities will talk about it in past tense once they leave college,” says Tamara L. Brown, one of the editors of African American Fraternities and Sororities: The Legacy and the Vision. “You would be hard-pressed to find somebody who’s a member of a Black Greek letter organization who talks about it in the past tense.”

Leadership qualities

Jeffries grew up in Brooklyn, the son of a social worker and a state substance abuse counselor. He attended a public school in the heart of the borough, and he later recalled the culture shock of arriving at Binghamton’s campus in 1988.

“I remember the opportunity to walk out at night at any point in time and feel completely at peace,” Jeffries told his college’s magazine in 2013. “That was a very different and liberating feeling as compared to the neighborhoods of central Brooklyn in the 1980s in the midst of the crack-cocaine epidemic.”

Jeffries’ office did not make the congressman available for an interview for this story.

According to Brown, Black Greek life in the U.S. arose from exclusion and racism in higher education. That context was particularly pronounced at predominantly white institutions, including the Indiana university where Kappa Alpha Psi was founded in 1911. The mission that helped launch the fraternity nearly eight decades before Jeffries joined carried over to each new chapter across the country, including Binghamton’s Mu Kappa chapter. Binghamton was over 80% white at the start of Jeffries’ freshman year, according to figures provided by the school.

David Cingranelli, a political science professor who became one of Jeffries’ favorite teachers, remembers that the future Congressman never hid his opinions, despite being one of the few Black students in his course. “I am always looking for students who are a little different from everybody else, who are not afraid to speak their mind,” Cingranelli says. “And he was that kind of guy.”

Though those who knew him back then don’t remember him speaking about national political ambitions, Jeffries was involved in campus politics and especially focused on uplifting students of color. He was involved with Binghamton’s Black Student Union, and in attempting to elevate his fraternity’s status on campus, he helped make communities of color more visible to the university as a whole.

As fraternity president, Jeffries coordinated and emceed the Mu Kappa chapter’s fashion show fundraiser. He participated in step shows, a Black Greek Life tradition, stomping and clapping in unison with other brothers. “Let me tell you, stepping is not easy, especially when you have to learn to twirl canes,” Cordero says. “He was very good at it. He loved stepping and I just remember him constantly harassing me to teach him different moves.”

The Kappa step shows soon became a draw for students of color across campus. Over time, white students came to watch, too. “All of a sudden, there was a part of the campus that just didn’t know that we even existed, and then we were like the Beatles on campus,” Cordero says.

Jeffries’ college days were marked by a playful streak—his pledge class was called “Demolition” because its four members were always breaking things—but even back then, his ambition foreshadowed a distinguished career.

After graduating Binghamton with a Bachelor’s degree in political science, Jeffries got a law degree at New York University. He practiced law for several years, representing CBS in a suit over Janet Jackson’s costume incident during the 2004 Super Bowl halftime show. In 2006, he was elected to the New York State Assembly. There, he partnered with current New York City Mayor Eric Adams, then a state senator, to author a law preventing police from keeping the names and addresses of New Yorkers they stopped, frisked, and released—many of them Black and Latino. In 2012, Jeffries won his seat in Congress.

Even now, when he’ll face relentless demands on his time as House Minority Leader by lawmakers, lobbyists and donors, Jeffries stays in touch with many of his frat brothers—both his classmates and others from the wider network of Black fraternities. “Being a member of what we call the ‘Divine Nine,’ that is, the traditional African American sororities and fraternities…creates a relationship with probably over a million people who have that connection in common,” says Georgia Rep. Bishop.

That network may be part of what set him on his path to Congress in the first place. In a video posted last year to his Kappa Alpha Psi chapter’s Instagram, Jeffries said he was grateful to Cordero for appointing him president of his pledge class—which preceded his eventual election to lead the whole chapter. According to Jeffries: “Never before had anyone seen leadership qualities in me outside of anyone in my family.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Mini Racker at mini.racker@time.com