Ever since the election, Nancy Pelosi says, congressional Democrats have been begging her to remain as their leader. Of course, she knew what they were really doing: currying favor, just in case.

“Our members were just exploding my phone to stay,” she says, “which is a nice thing, because if I don’t stay, then they’ve gotten the points for saying ’stay,’ and if I do—“ she trailed off, laughing. No matter what she decided, they knew it would be in their interest to be on her good side going forward.

For two decades, it has been in every congressional Democrat’s interest to stay in Pelosi’s good graces. Since winning her first leadership position in 2001, she has ruled the House Democratic caucus with an iron fist and a velvet glove, keeping her fractious party in near-lockstep during historically tumultuous times. From the Iraq War to the financial crisis, through health-care reform and government shutdowns, through two presidential impeachments, a pandemic and an insurrection attempt, she has been a constant force and consummate operator. No national politician of her era can match her combination of legislative prowess, vote-counting savvy, negotiating skill, and fundraising ability.

On Thursday, it was finally time to move on—sort of. Shortly after noon, she gave a brief speech on the House floor, announcing that she would not seek re-election as leader of the House Democrats. It was time, she said, “for a new generation to lead the Democratic caucus that I so deeply respect.” Yet she couldn’t bring herself to step away completely: she owed it to her constituents in San Francisco, she said, to stay on as a rank-and-file member of Congress and finish her two-year term. Like the man who fakes his own death and then sneaks into the funeral, she would stick around to see how her people tried to get along without her.

Just after her speech, the 82-year-old House Speaker sat at a white-clothed table in a small, ornate room off the House floor known as the Board of Education, a hidden chamber where former Democratic Speaker Sam Rayburn used to hole up and relax. Then-vice president Harry Truman was playing cards with Rayburn here in 1945 when he learned that FDR had died and he would become President. One wall Rayburn had painted with a Texas seal; on two others, Pelosi recently added her own touches: a painting of the Golden Gate Bridge, and a tribute to women’s suffrage.

Pelosi was contemplating the not-quite-end of the era and struggling to unwrap a package of chocolate-chip cookies. “What was important to me was how we did in the election, because we were on a bad path,” she told a small group of reporters. “Storming the Capitol, really? And the reaction of Republicans, not taking a stand? And I knew we could win.”

Her party had just lost the House, weeks after a crazed intruder broke into her California home and bludgeoned her husband with a hammer. But it hardly felt as if Pelosi was giving up in defeat. In an election that history and many forecasters predicted would deliver a Republican wave, Democrats surprisingly held their own. The resulting GOP majority will be a narrow one, with the Senate remaining in Democrats’ hands.

The Oct. 28 attack on Paul Pelosi, the Speaker’s husband of 59 years, influenced her decision to remain in Congress, but not in the way many people thought. “It was not, ‘Oh, well, since they did that, I can’t even think of something else,’” she says. “No, it had the opposite effect. I couldn’t give them that satisfaction.”

Read More: Nancy Pelosi Doesn’t Care What You Think Of Her.

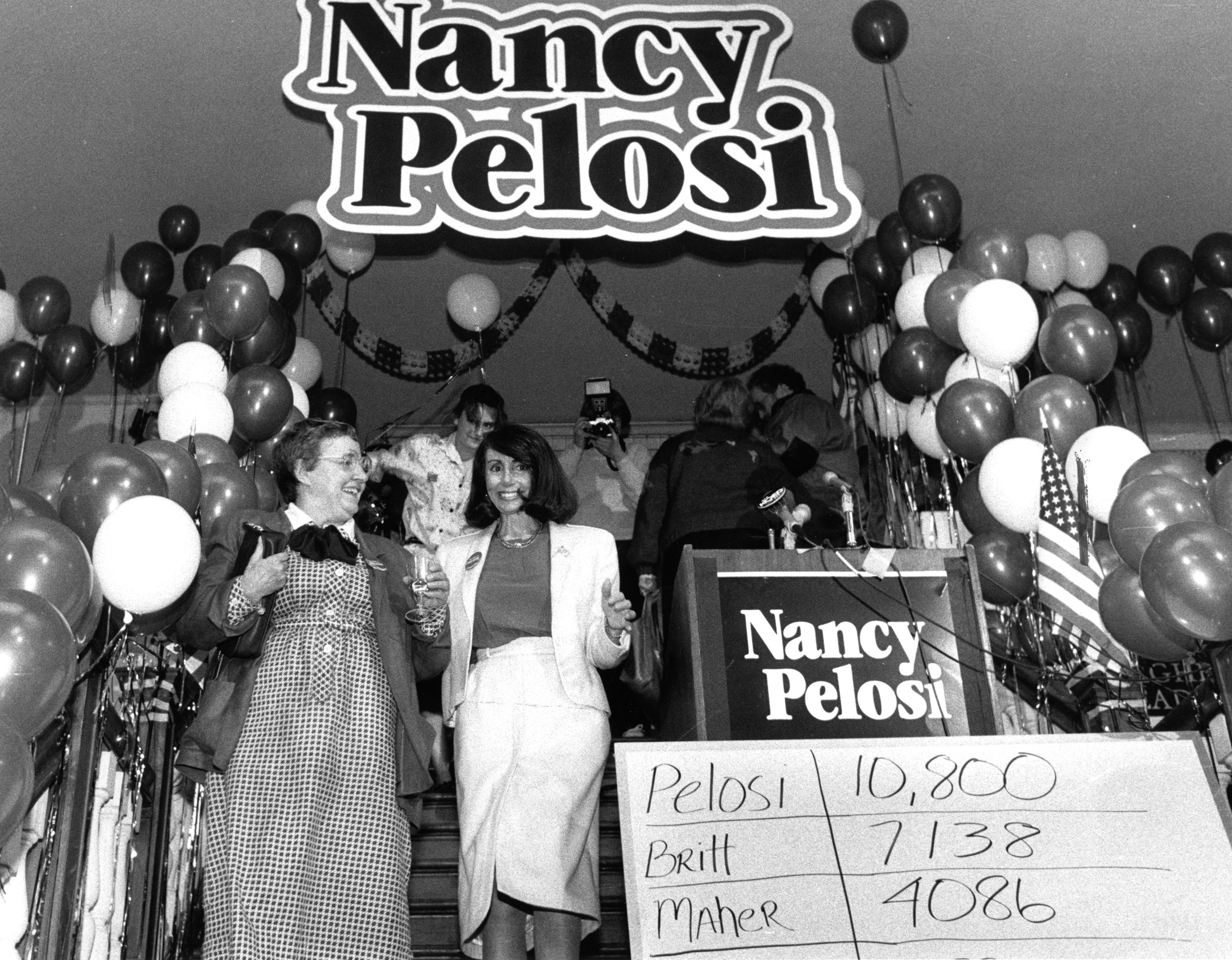

This steely tenaciousness, this refusal to let others decide her path, is a running theme of my biography of Pelosi. It has been the hallmark of her political career, from forcing her way into the male-dominated ranks of congressional leadership to standing up to former President Donald Trump. As the youngest child and only daughter of three-term Baltimore mayor Thomas D’Alessandro, politics was in Pelosi’s blood; she first set foot on the House floor as a young child, when her father was serving in Congress. But when she finally ran for office herself at the age of 47—after raising five children and serving for decades as a political fundraiser, strategist and volunteer—it was from a different coast, under a different name, with a political identity all her own.

Ask Pelosi about her legacy, and the first thing she’ll mention is the Affordable Care Act. However flawed and incomplete the 2010 law’s guarantee of universal access to health care may have proven, it represented the fulfillment of a century of liberal aspirations, and the pinnacle of Pelosi’s legislative craft. She moved mountains to get it through the House, at one point nearly breaking down in tears as she begged a group of liberal feminists to swallow an unsavory compromise on abortion funding. Then, after a special election robbed Democrats of their supermajority in the Senate, she urged then-President Obama not to give up on the historic legislation. “If the gate’s closed, you go over the fence,” she said at the time. “If the fence is too high, we’ll pole-vault in. If that doesn’t work, we’ll parachute in. But we’re going to get health-care reform passed for the American people.” Though most of the drama around the bill’s passage revolved around the Senate, it never could have happened without Pelosi’s determination and drive.

She did it knowing there might be a political cost, and indeed there was. Republicans gained 63 seats in the House in the 2010 midterm elections, an election in which Pelosi was a central figure. Republicans made her the subject of millions of dollars’ worth of attack ads across the country, capitalizing on their base’s visceral loathing of her and giving Peosi unusual prominence for a congressional leader.

But Pelosi believed in gaining power not for its own sake but in order to do something with it. Obamacare is part of a legacy that includes two decades of liberal policy victories, from allowing gay people to serve openly in the military to the historic climate investments of this year’s Inflation Reduction Act. “This is a very difficult job,” she told us. “You have to really know how to be a legislator.”

These legislative successes were all the more remarkable for the era in which they came. Faced with unrelenting Republican opposition, she held together the diverse Democratic caucus and drove a hard bargain in negotiations across the aisle. After Donald Trump became president, she led her party back to power, becoming Speaker for the second time in 2019 in the middle of a government shutdown over border-wall funding. Pelosi refused to budge, and Trump soon capitulated. She would go on to impeach him twice while simultaneously negotiating with his Administration to secure trillions in COVID-19 relief funding.

Read More: Why Nancy Pelosi Is Going All In Against Trump.

Pelosi rejects the notion that she bears any blame for the toxic state of politics. “I don’t take any responsibility for what the Republicans have done to the Congress. This is not about gridlock,” she says. “This isn’t about some sort of equivalence between Democrats and Republicans. They are anti-science, anti-government, and that’s where they are.”

The GOP’s lack of decency was apparent in many Republicans’ reaction to her husband’s attack, Pelosi says. “Just think if your spouse were in that situation and people would make a joke of it, like it was funny,” she added. “Collecting money for bail for the perpetrator, putting out a conspiracy theory about what it was about. It’s so horrible to think that the Republican Party has come down to this.” This attitude, she says, was part of what voters recoiled from the midterms.

Pelosi never groomed a successor, something for which she was often criticized. Ambitious Democrats languished for decades waiting for an opening in House leadership. She has often expressed the view that power is never given but must be taken by those who seek it. “I didn’t think that was the right approach, to anoint somebody,” she told us Thursday. “It’s really important for people to have the legitimacy that they were chosen by the members.”

A free-for-all appears unlikely. Pelosi’s longtime deputy Steny Hoyer, a fellow Marylander who has known her since they worked for the same Senator in 1963, announced Thursday that he would also stay in Congress but not in leadership. Rep. Hakeem Jeffries of New York, the 52-year-old chair of the Democratic caucus, appears almost certain to win the minority leader position in the Democratic leadership elections scheduled for Nov. 30, becoming the first Black man to lead a party in Congress. The first woman Speaker, in passing the torch, will make history once again.

Pelosi intends to spend the next two years in valedictory mode. “My life ahead is full of thank-yous,” she says, to her constituents and all the others who have supported her over the years. She does not plan to serve on any committees and she does not want to serve as a sort of shadow speaker from the sidelines. “Thanksgiving is coming,” she says. “I have no intention of being the mother-in-law in the kitchen saying, ‘My son doesn’t like the stuffing that way, this is the way we make it in our family.’ They will have their vision. They will have their plan. It’s up to the caucus to decide which way they want to go.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Molly Ball at molly.ball@time.com