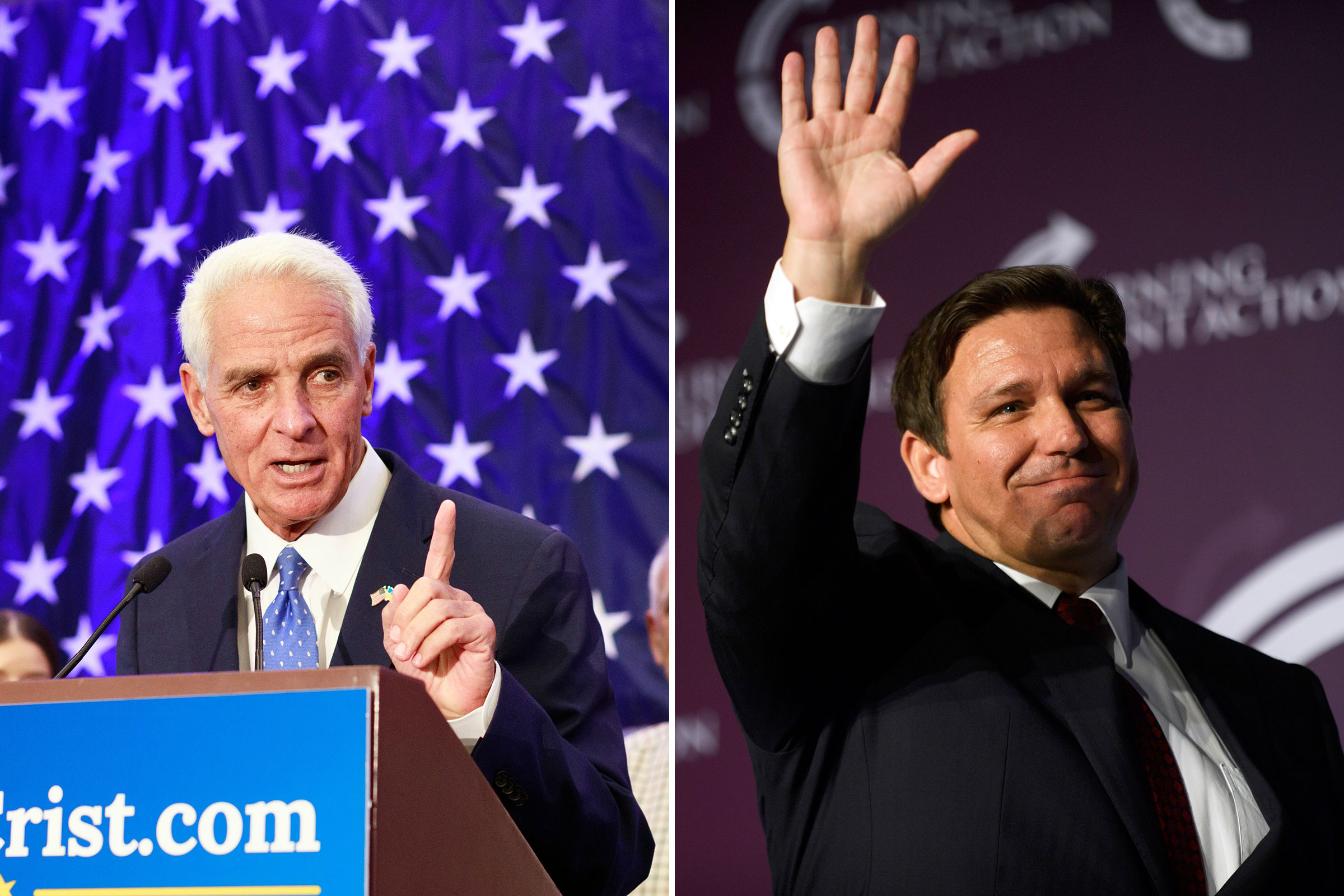

The man who thinks he can stop Ron DeSantis slides into a booth at a dimly lit bar in Tallahassee, around the corner from the Florida Capitol. “The stuff he keeps doing to remind Floridians how bad he is, it’s—I can’t believe it,” former Rep. Charlie Crist says, doing his best to sound genuinely astonished.

The day before, DeSantis, Florida’s swaggering right-wing governor, had drawn national headlines by shipping about 50 Venezuelan asylum seekers from Texas to Martha’s Vineyard without warning. “I mean, what’s that got to do with Florida?” Crist says. “I think he’s overreached.”

DeSantis, as you may have forgotten, is running for reelection this year, and Crist is the Democratic nominee opposing him. Crist isn’t upset about DeSantis’s alleged overreach. He’s delighted. ”I’m not a psychologist,” he says, dumping a creamer into his cup of coffee. “But I think he’s so laser focused on 2024 and the Republican nomination—I think he’s intoxicated by it, and I think that is messing up his judgment. And, you know, I’m not complaining about it. I think it’s helping us. I think we’re going to win.”

The political world is not so convinced. While DeSantis dominates the news, his reelection this year has been all but taken for granted, and Crist, a former Republican governor and two-time statewide loser, has been all but ignored. To most political observers in both parties, the race is barely a speedbump as DeSantis steamrolls to national prominence. Amid the daily drumbeat of speculation about DeSantis vs. former President Donald Trump, his constituent and frenemy, DeSantis vs. Crist merits barely a mention.

Yet DeSantis, 44, is hardly battle-tested. Four years ago, he was a little-known Republican congressman who got elected governor in a historic squeaker, defeating the since-indicted Democrat Andrew Gillum after a recount by less than half a point—just 30,000 votes out of more than 8 million cast. Since then, DeSantis has made a splash on the national stage thanks to his handling of COVID-19 and talent for culture-war provocations, from taking on Disney and critical race theory to the recent migrant gambit. He’s increasingly seen as a frontrunner for the GOP presidential nomination, whether or not Trump enters the race. And Democrats seem powerless to stop him.

It’s a befuddling situation in what used to be America’s paradigmatic swing state: rather than mount a massive effort to take out or at least bruise DeSantis, Democrats are effectively allowing the Republican they fear most to coast to reelection. Crist, 66, is a party-switching, baggage-laden retread more disliked by Floridians than DeSantis. He was forced out of his congressional seat by DeSantis-engineered redistricting and wound up with the nomination after other potential candidates passed on the race, intimidated by DeSantis’s war chest and iron grip on the state’s political landscape. Crist’s fundraising is paltry—barely a tenth of DeSantis’s staggering $180 million. Polls show him lagging by an average of 6 points, according to FiveThirtyEight. And while national Democrats privately lament the situation, they have no plans to invest heavily in the campaign.

“Florida was once the ultimate swing state, and if you look at the stuff DeSantis does, you would think there would be a major backlash,” says Jessica Taylor of the nonpartisan Cook Political Report, which has rated the race “Likely R.” “But he’s only gotten stronger, and now we see him emboldened to do other controversial things. Many Democrats wish this was the year they could take him out, but it doesn’t seem to be shaping up that way.”

Crist, of course, rejects this perception. Asked for evidence, he cites mainly vibes. “There’s an energy here, and it’s palpable,” he says, particularly since the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, triggering a national women’s mobilization. If DeSantis wins reelection, he warns, “it would be a disaster for the United States of America, because he immediately starts running for President on November 9.”

After our interview, Crist and I walk out of the bar, a storefront in a two-story strip mall. There’s a big banner hanging from the upper balcony. It says: Reelect Governor Ron DeSantis.

Earlier that day, Crist arrives at Florida’s historic capitol, a glass-domed building whose red-and-white striped awnings and surrounding palm trees give it a banana-republic feel. A motley group of three dozen supporters have gathered on the stone steps, holding purple abortion-rights placards that say “The Choice Is Choice.” (Oddly, the placard on the lectern has it the other way around: “Choice Is the Choice.”) By the numbers, Florida is the most pro-choice red state in the country, and Crist hopes to make abortion the campaign’s central issue.

Taking the lectern in a gray plaid suit and yellow-striped tie, a little black fan whirring at his feet to keep him cool, Crist accuses DeSantis of using the migrant issue to change the subject from abortion. The governor signed a 15-week abortion ban with no exceptions in April, but has conspicuously avoided the issue since praising the Supreme Court’s decision in June. “This governor is an extremist, no question about it,” Crist says. “If Ron DeSantis wins, and he will not, he will ban abortion completely.”

Crist was once the bright new hope of his party—the Republican Party. As a GOP state legislator, attorney general and governor starting in the 1990s, he long described himself as pro-life. But in practice, he repeatedly opposed abortion restrictions, angering the right. Elected governor as a Republican in 2006, he promised conservatives he would sign an abortion ban, then publicly disavowed it. Crist’s critics say it’s part of a career-long pattern of trying to have things both ways.

In our interview, I ask if he now supports any limits on abortion. He dodges the question. “I support Roe v. Wade—I think that’s appropriate,” he says. “I think the real question, though, is why doesn’t Ron DeSantis trust women to make their own decisions? It’s not about what restrictions or where are you on the scale.”

Crist’s breaking point with the GOP wasn’t over abortion. In 2009, he accepted Florida’s allotment of stimulus funds from the Obama administration—the only Republican governor to do so—and hugged the Democratic president when he came to Ft. Myers to tout the investment. When Crist tried to go from the governor’s mansion to the U.S. Senate the following year, the Obama hug became Exhibit A for his Republican primary opponent, a little-known conservative state legislator named Marco Rubio, who called Crist a squish and rode that year’s Tea Party wave. Crist dropped out and ran as an independent instead, but lost by 20 points.

Read More: How Democrats are Responding to DeSantis’ Migrant Stunt.

Today, he has recast his ejection from the GOP as a sort of martyrdom for his loyalty to Obama and refusal to pander to the racist right. He argues that he spotted where Republicans were headed long before Trump. “I don’t want to ever paint with too broad a brush here, there are fine Republicans in Florida and in America,” he tells me. “But I saw an element that wasn’t just upset with me because I was with the Democratic president. I was with the first Black President. And that really disturbed me, and I just couldn’t stay there anymore.”

Crist spoke at the 2012 Democratic convention, then ran for governor as a Democrat in 2014 and narrowly lost to now-Sen. Rick Scott. In 2016, he won a Democratic-leaning congressional seat in his hometown of St. Petersburg. He served three terms in Congress, compiling an unremarkable record as a reliable Democratic vote. But this year, congressional redistricting turned Crist’s district deep red, and GOP nominee Anna Paulina Luna, a Trump-endorsed election denier, is heavily favored to win it.

The aggressive redistricting plan was the work of DeSantis, who pushed to give the GOP an even bigger advantage than the Republican legislature had dared and defied court challenges to keep it in place. The resulting map eliminates four Democratic-leaning seats to give the GOP as many as 20 seats in Congress to just 8 for Democrats, despite the state’s narrow partisan divide. It’s among the ways Democrats have been strong-armed out of power in Florida in recent years, leading many to argue that the state Trump now calls home has become more red than purple. Last year, the number of registered Republicans in Florida surpassed the number of Democrats for the first time in history, an edge that is now 270,000 strong.

Things looked different just four years ago. Democrats came close to winning both top-of-the-ticket races in 2018: in addition to the narrow loss for Gillum, Republican Rick Scott defeated then-Senator Bill Nelson by just one-tenth of a percentage point, the closest Senate race in state history. Demoralized Florida Democrats commissioned a soul-searching report that faulted the party’s voter registration, messaging, candidate recruitment, outreach and turnout efforts, and stressed the need to rebuild from the ground up. “2020 will be one of the most consequential years in history, and we must act now,” the report stated. “The path to a Democratic White House will go through Florida, and we will waste no time charting that path.”

That hopeful prediction would not come to pass. Biden and the Democrats spent tens of millions on Florida in 2020, but Trump won the state by 3 points—the biggest presidential win there for any candidate in more than two decades. To some Democrats, it was proof the state was a lost cause. The increasing diversity they long hoped would work in their favor has been offset by an influx of white retirees and a slippage among working-class voters of color, particularly Black and Latino men. “Is Florida really a swing state? I think Democrats are pretty clear-eyed about the demographic trends working against us,” says Joel Payne, a Democratic strategist. “It does feel like DeSantis has consolidated Republican power in the state. I don’t think it’s gone forever, but I think it’s solidly red for now.”

DeSantis’s strength and Crist’s early entry into this year’s gubernatorial primary drove other potential candidates out of the race. Democrats privately mutter that some of them might have posed a greater threat to DeSantis. Rep. Val Demings, a former Orlando police chief briefly touted as a potential Biden running mate, was poised to run for governor, but decided to run for Senate against Rubio instead. (Polls show that race closer than the gubernatorial contest, though Rubio, too, is favored to win.) That in turn pushed out Rep. Stephanie Murphy, who had been eyeing a Senate run; she declined to run for reelection, depriving the party’s already-thin bench of a moderate seen as a rising star. Another candidate in the gubernatorial primary, state Sen. Annette Taddeo, eventually dropped out to run for Congress, leaving state agriculture commissioner Nikki Fried, 44, as Crist’s only opponent. Fried argued that, as a fresh face and a woman, she’d be the stronger candidate against DeSantis. But she was no match for Crist’s name ID, and he easily defeated her in the Aug. 23 primary.

Hopeful Democrats tout Crist as a Joe Biden-like candidate: a broadly acceptable moderate who can turn the race into a referendum on his polarizing opponent without drawing too much attention to himself. Unlike some Democrats this cycle, Crist doesn’t shy away from the unpopular president. “I think he’s the man for the moment,” Crist tells me, pointing to Biden’s foreign policy and legislative achievements. “I think people are really beginning to appreciate more and more how blessed we are to have him as our President right now.” Crist plans to appear with Biden when he visits Orlando this week, and is hoping to campaign with Obama as well, though the former president has yet to commit.

Crist’s own campaign admits it’s an uphill battle, particularly without an influx of cash from the national party. “The Republican spin machine has been working overtime since 2016 to market Florida as some kind of Republican stronghold as a way of deterring Democratic investment in a swing state,” says Joshua Karp, Crist’s senior adviser. “There are multiple statewide races with Florida Democrats in striking distance if we have allies who join us in the fight.”

DeSantis’s critics fret that the failure to put up more of a fight against him enables Republicans to spend money elsewhere and allows DeSantis to save his own campaign cash for a future race. DeSantis’s apparent strength, they say, is partly due to Democrats’ weakness. “If there was a functional Democratic Party in the state of Florida that could get out of its own way, they could do it,” says Rick Wilson, the anti-Trump Lincoln Project cofounder who was formerly a longtime GOP consultant in Tallahassee. “There’s a pool of votes out there sufficient for a Democratic majority at the statewide level. But these guys couldn’t organize a two-car motorcade.”

Shortly after my talk with Crist, DeSantis strides into an airplane hangar in Daytona Beach, four hours to the south, drawing loud cheers from the business-attired crowd seated on folding chairs. He’s there to announce $30 million in new state funding for aeronautics and tech workforce training. But the press conference naturally centers on DeSantis’s surprise migrant scheme.

Republican governors in Texas and Arizona—states that are actually on the border, which has seen an unprecedented surge this year—had previously staged similar provocations; Texas Gov. Greg Abbott even sent a busload to Vice President Kamala Harris’s residence. But it was DeSantis who managed to hijack the news cycle.

Read More: Inside Migrants’ Journeys On Greg Abbott’s Free Buses to Washington.

Questioned about the ploy, DeSantis seizes on reports that Biden has convened an emergency meeting of his Cabinet to deal with the issue: “He didn’t scramble when we had millions of people pouring across the southern border,” the governor taunts. “It’s only when you have 50 illegal aliens in a wealthy, rich enclave that he scrambles.” As for what business Florida has taking people from Texas and sending them to New England, DeSantis claims they had been “profiled” as the types of would-be immigrants who are likely to eventually get to Florida. It’s as if he’s already running against Biden—and any other Democrat who might get in his way. Gavin Newsom, the governor of California, has just challenged him to a debate, and DeSantis gets off a final zinger about Newsom before ending the event: “I think his hair gel is interfering with his brain function.”

The press rarely gets to ask questions of DeSantis, who has made the mainstream media one of his many punching bags. In August, he released a swashbuckling minute-long campaign video modeled on Top Gun (“Top Gov”) that showed DeSantis, a Navy veteran, strutting around in a flight suit and aviator sunglasses interspersed with clips of him berating reporters at press conferences. He prefers to speak to his party’s base, appearing on Fox News and Newsmax and doling out administration announcements to Breitbart and the like.

This is not the typical posture of a politician trying to win over the electorate of a purple state. But DeSantis, whose campaign naturally did not respond to my emails, is clearly feeling confident—and looking beyond November. For his first couple years in office, he rebuffed offers to speak at candidate or interest-group events in other states, insisting he was focused on Florida. But since last year, he’s been crisscrossing the country stumping for GOP candidates, a sign of both his star power in the party and his lack of concern for the perception that, as Crist puts it, “he cares more about the White House than any Floridian’s house.”

The typical purple-state political strategy would be to tack to the center, but DeSantis has not done that either. The fact that he has gone hard-right and remained broadly popular—one recent poll put his approval rating at 51%, vs. 43% for Crist—is a major component of his appeal to Republicans. Just as Bernie Sanders’ liberal acolytes contend that his socialist vision would galvanize the electorate more powerfully than the centrists the Democrats tend to nominate, DeSantis’s many fans in the GOP see him as proof that right-wing policies, far from provoking a backlash, actually appeal to voters. He would, they hope, do to America what he’s done to Florida: turn the political current to his will rather than bending in the wind. The bigger the margin he’s able to rack up as he sails to reelection, the greater the currency this argument would have in a GOP presidential primary. Many conservatives see him as a smarter version of Trump, with the shrewdness and focus to implement a vision Trump only flailed at haphazardly.

Plenty of liberals agree. To them, this makes DeSantis a more dangerous version of Trump. But when I ask Crist if he believes this to be the case, he doesn’t seem to have followed the debate. “He may well be, I don’t know,” he says. “I think he’s very calculating. You know, for a guy who went to Harvard and Yale to be this ogre-like, it’s hard to explain, except that he’s politically ambitious.” Crist is a famously touchy-feely, feel-your-pain kind of pol, the kind of campaigner who remembers everyone he’s ever met, cites the Golden Rule as his lodestar, and will stay on the selfie line till he’s kicked out of the building. It’s no surprise he’s not interested in abstract debates about authoritarianism. He’s a feeler, not a thinker.

It’s not as if Florida doesn’t have problems: the economy is roaring, but housing prices and insurance rates have skyrocketed, creating an affordability crisis. And it’s not as if DeSantis doesn’t have liabilities: as his 2024 stock rises, GOP insiders have grumbled about his brusque manner and tight inner circle. Several of his campaign ads feature constituents praising his policies while he is barely seen, suggesting his own team may grasp that, as with Trump, many of his supporters like what he’s done better than they like him personally.

DeSantis and Crist briefly served in the same state delegation in the House, but they only interacted once that Crist can recall. “My first term in Congress was his last, and I remember the encounter we had,” Crist tells me. The two congressmen were in the Capitol and had just emerged from neighboring elevators on the way to the House floor for a vote. “I’m a friendly guy, and I said, ‘Hey, Ron, how are you?’ And he goes, ‘Fine,’” Crist recalls, face drooping in imitation of DeSantis’s flat affect. “That was it. I mean, weird! And so I said to myself, well, you’re a good guy, Charlie, press on. And I told him, ‘I heard the rumors that you’re thinking about running for governor next year, and as one who’s been one, if it works out for you, you’ll find out that it’s the greatest job you can ever have.’ And he goes, ‘Thanks,’ and turns around and walks away.”

Crist passes his hand up and down in front of his perma-tanned face, the universal gesture for stone-faced. To him, there is nothing stranger than an introvert, nothing stranger than a disagreeable person. “That was it. And I thought, where is the soul in that person? It’s just odd to me that anyone would be that cold. Unsettling, a little bit. And I guess now I know why, seeing what he’s done for four years.”

Then Crist turns the subject back to abortion, the issue he’s sure will turn the race in his favor and give DeSantis a shock. But if Democrats can’t stop DeSantis, they may only end up making him stronger.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Molly Ball/Tallahassee at molly.ball@time.com