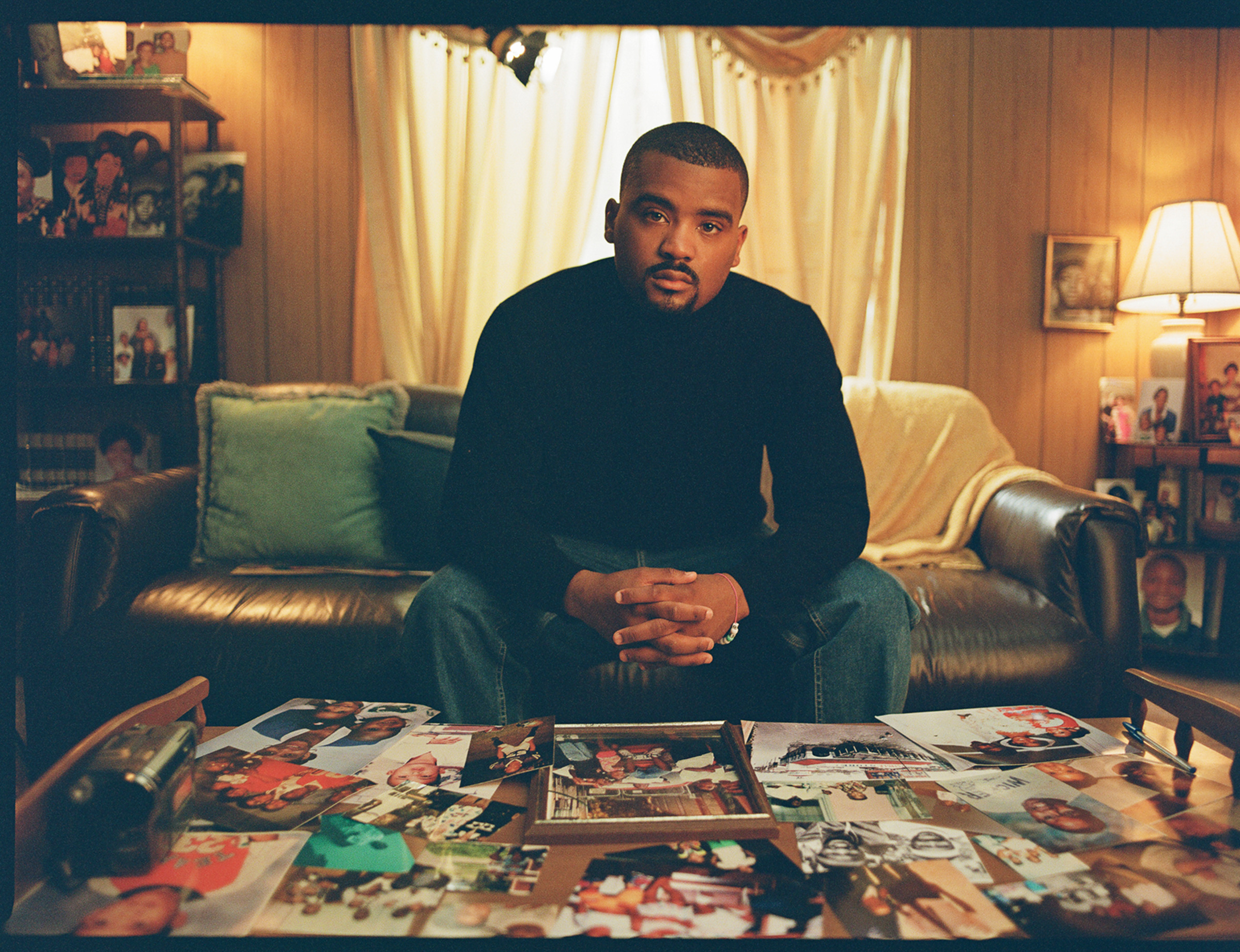

Edward Buckles Jr. was 13 when Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans. His family fled the city just in time, but the storm changed him forever. After years spent as an educator and filmmaker, Buckles decided to make a film about the children—including himself—who were affected by the storm. Katrina Babies (produced by TIME Studios) is an intimate documentary about life and loss that focuses on those who were 3 to 19 years old when the storm struck. Through moving firsthand accounts, including interviews with his cousins and parents, Buckles wants his film to “change the narrative and own the narrative of what’s happening with young New Orleans.”

In a conversation with journalist Soledad O’Brien, who covered the aftermath of Katrina extensively for CNN, Buckles discussed his film and his hope for the future.

O’Brien and Buckles’ conversation is paired with a new TIME cover, featuring art by Charly Palmer. The piece is called Black Boy Fly and celebrates the ability of young people to thrive despite lives interrupted by tragedy and other challenges. He says his inspiration is the Black child’s right to their own, untroubled childhood, even in the face of challenges. Palmer is the author and illustrator of the 2022 children’s book, The Legend of Gravity and is the co-author with his wife, Dr. Karida L. Brown, of the forthcoming children’s anthology, The Brownies Book: A Love Letter to Black Families. In 2020, a Palmer painting called “In Her Eyes” graced the cover of TIME.

Katrina Babies will premiere on Aug. 24 on HBO Max.

Soledad O’Brien: What was the story that you wanted to tell?

Buckles: I got this idea when I was 20 and studying documentary at Dillard [University]. I’m watching all of these films, and I’m really being inspired. And then I’m like, What’s a documentary that I would tell about my life? And nothing came to me for a very long time. One day my cousin Tina called me. And she was just crying, because she was still displaced during the holidays. That’s when it finally hit me. And I was like, Yo, I want to tell a story about what the children went through during the storm. Because on that call, she told me what all of my cousins had been through. I grew up in post-Katrina New Orleans, and I was exposed to everything.

It seemed like it was hard for you to know the story, because you were in the story.

I was not prepared for the weight and the stories that came with that. So that’s why it took me seven years to make it. But it wasn’t until Year 6 that I actually inserted myself into the film. I was very resistant.

Why were you resistant? It really is your story seen through other people’s experiences as well.

I was resistant because the only thing that I can think about is survivor’s guilt. I was fortunate enough to follow my mom’s faith, and she evacuated us at the 11th hour. Something that we do a lot in our communities—I don’t just want to say in New Orleans, but something that we do in my type of neighborhoods—is we compare trauma. We wear our trauma as armor. So, because I wasn’t actually in the water, I always said, “I don’t have trauma.” There are people being airlifted off of roofs and people who drowned and people who lost their parents, why do you need to be in this story? But then once I got older, my trauma started to surface in different ways. It just wasn’t the same as everybody else’s, but trauma is trauma. This film helped me to begin that process of finding my own trauma and healing.

Was it hard to go back and look at the videos? It was hard for me to watch, having just spent so much time in New Orleans covering that story.

It was hard to watch that archival footage, but I learned a lot. I was hearing a lot of crazy stuff that these different reporters and journalists were saying. It really allowed me to grow a whole different respect for people like yourself who are doing it the right way, who are doing it with love and empathy, and really trying to give voice to the voiceless. But it also allowed me to see the other side as well and how our Black bodies were being spoken about.

What is it like to lose your future when you’re 12 years old?

What does it mean to lose your identity when identity is connected to everything that has been washed away? In New Orleans we find out who we are through our neighborhoods. We find out who we are through our history, and all of that was washed away. When I became a high school teacher, it was the most interesting thing because every high schooler is on their journey. But kids in New Orleans really don’t know who they are, don’t know how to find who they are because they’re moving around so much, because they don’t have any baby pictures, simple things like that. They don’t know where their childhood home is. If you layer that on top of everything else that’s happening in New Orleans, it’s hard to grow up. What happened 17 years ago is still impacting children that were not born during the storm. It’s still impacting their future because of the conditions that it left.

Why does it piss you off so much when someone refers to the folks who were displaced as refugees vs. evacuees?

It makes me mad because by definition, we are not refugees. We were being treated like refugees, but we are American, right? We are from here, right? We fight, and we would die for this place, right? I thought that calling us refugees was lazy. And don’t be lazy with how you are labeling us because words are things, right? So I just think that it’s the lack of empathy, and it’s the lack of respect for Black people and Black bodies. It’s like one of those things where I’m not mad. I’m just disappointed.

Why do you think so many people who are very young babies in Katrina haven’t gotten help for what is clearly a real trauma?

Growing up disenfranchised and not having access and mental-health resources. I think that’s the reason that talking about our trauma is not our go-to, but using our strength and resilience is.

What do you want people who watch this film to walk away with?

Hurricane Katrina was in 2005, and it still echoes. I believe that if we get resources and tools, we can be a great city. I just wanted to shine light on us and start healing.

Correction, Aug. 22

The original version of this story misstated Edward Buckles’ age when Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans. He was 12, not 13.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com