In a wood-paneled office Mongolia’s prime minister, Luvsannamsrain Oyun-Erdene, sits in front of a gilt framed painting that depicts a warrior and fawn. “It’s called Hero Going to War, by the Mongolian painter Otgontuvden Badam,” explains the chief of staff. But, sandwiched between Russia and China, the last thing Mongolia needs is war or heroics of any kind.

Oyun-Erdene is acutely aware of this as he settles in a leather armchair for a video interview in July. “We are located geopolitically between two superpowers,” says the Harvard Kennedy School alum, who became prime minister in January last year after serving two years as chief cabinet secretary. The nation—while twice the size of Turkey—is home to just 3.3 million people. “We are very sensitive to global economic fluctuations,” he says, “which is a blessing and a curse at the same time.”

The blessings are straightforward: Mongolia has the world’s biggest known coal reserves, second largest reserves of uranium, and one of the largest of silver. Throw in significant deposits of gold, copper, iron ore, phosphorus and zinc, and it’s clear why spiking commodity prices are a boon for its coffers.

Read More: How Mongolia Typifies the Problems Posed to Small Countries by China’s Rise

The immediate curse, however, is inflation. The price of fuel—especially the diesel vital to nomadic communities scattered across the steppes—is soaring. Russian President Vladimir Putin’s Feb. 24 invasion of Ukraine, and ensuing Western sanctions, have also led to spikes in the cost of Russian chemicals (used for mining explosives, fertilizer, and agricultural feed) and food, of which the Russian Federation is one of Mongolia’s biggest suppliers.

Tourism, which made up 7.2% of GDP and accounted for 7.6% of employment in 2019 has now collapsed—costing the national economy some $470 million from the start of the pandemic until March, according to government figures—and not just because of COVID-19. The European embargo of Russian air space, as a result of the war in Ukraine, has led to a slashing of flights to Mongolia’s capital Ulaanbaatar. Oyun-Erdene laments the “instability of the international community” and its effects on his country.

The situation threatens his bid to transform Mongolia from an impoverished agricultural economy—about a third of the population lives in some form of poverty—into a modern minerals exporter with a startup-friendly environment, plenty of international investment, and a thriving financial services sector. Upon taking office last year, he implemented an ambitious plan, Vision 2050, to increase GDP per capita almost tenfold, from $4,009 to $38,359 by the middle of the century. “We have done our homework and now we have to put these developments into real life,” Oyun-Erdene says.

Oyun-Erdene was born in Ulaanbaatar in 1980 but grew up in Berkh on the Eastern Mongolian Steppes. The village is known for its fluorspar mine—a mineral ore mix of calcium and fluorine—and has 10 times as many heads of livestock as people. He had a severe speech impediment until he was 5 years old, but overcame it with the patient coaxing of his grandfather—a renowned Buddhist abbot, chess master and instructor of mathematics and Mongolian language—from whom he adopted the patronymic Luvsannamsrai.

Oyun-Erdene did well academically, earning degrees in journalism and law, and then public policy at Harvard. (His Ivy League schooling marks him out from a previous generation of leaders mostly educated in the former Soviet bloc.) At the age of 21, Oyun-Erdene ran the governor’s office in Berkh. Later, he worked overseas for the NGO World Vision. The foray into international development left him mindful of the problems his own country faced. He later wrote of being “saddened to see how bureaucratic, corrupt, and politically divided” Mongolia had become by comparison with much of the world.

The country’s reliance on commodities was also problematic. As prices soared in the early 2000s, Mongolia briefly became the world’s fastest-growing economy, earning the nickname “Minegolia.” Prospectors from North America and Europe quaffed expensive Scotch in Ulaanbaatar nightclubs. But the mineral boom was short-lived, and by 2017 Mongolia went cap in hand to the International Monetary Fund for a $5.5 billion bailout.

Oyun-Erdene had been elected as an MP the previous year and grew in prominence by helping to organize mass protests against corruption. Today, commodity prices are high again and Oyun-Erdene hopes to avoid another cycle of boom and bust by modernizing Mongolia’s economy through infrastructural developments—there are dozens of projects underway, from hydroelectric dams to railways and power plants.

He has also earned himself tremendous political capital by renegotiating a deal with mining giant Rio Tinto for the $6.75 billion expansion of the vast Oyu Tolgoi copper and gold mine in the Gobi Desert. In December, the Australian firm agreed to write off more than $2 billion in loans that Mongolia’s government was using to fund its share of the development. The renegotiation included guarantees to safeguard scarce water resources vital to nearby herder communities and to ensure that proper social infrastructure was provided for workers attached to the mine. Rio Tinto hopes that the move will “deliver greater economic value to Mongolia.” Oyun-Erdene says he wants such cooperation to be applied to “other mining locations.”

Modernization is badly needed. China accounts for over 90% of Mongolia’s exports—and they mostly travel by road. Thousands of rumbling, sooty trucks—loaded with minerals, coal or ore—make their way to the Chinese frontier, where tailbacks regularly span 15 miles. Drivers can wait for up to a week to cross. Mongolia is nowhere near its export capacity due to such basic infrastructure constraints.

Complicating the issue, Beijing’s draconian zero-COVID policy means that it sporadically seals the border, blocking trade. In June, a Chinese official suggested that its pandemic control measures may last for five years. Oyun-Erdene expresses concern for the “negative consequences” this has for his country, adding that “the zero-COVID policy of China is, of course, not only Mongolia’s issue, but a global economic issue.”

Landlocked Mongolia’s exports to other nations must also use Chinese ports. In a bid to ensure that “railway exportation will not depend on the COVID-19 situation,” Oyun-Erdene hopes to open five new rail crossings with China by the end of 2022.

Mongolia’s foreign policy requires similar agility. “If Mongolia is not engaged, then we are truly landlocked and geopolitically really challenged,” says Bolor Lkhaajav, an analyst on Mongolian foreign relations.

The country’s “third neighbor policy”—a long-running strategy of cultivating relationships beyond China and Russia—was born out of such concern. Western nations have been responsive in recent months, sensing kinship with a democratic country in an adversarial region. In late June, Germany announced that it was restarting bilateral aid with Mongolia after a two-year break. From July 1, Mongolians became eligible for Australia’s coveted holiday visa program.

“Broadly speaking, the West is reawakening to values diplomacy, energizing democracy promotion,” says Prof. Julian Dierkes, a Mongolia expert at the University of British Columbia. “This is, of course, where Mongolia triumphs.”

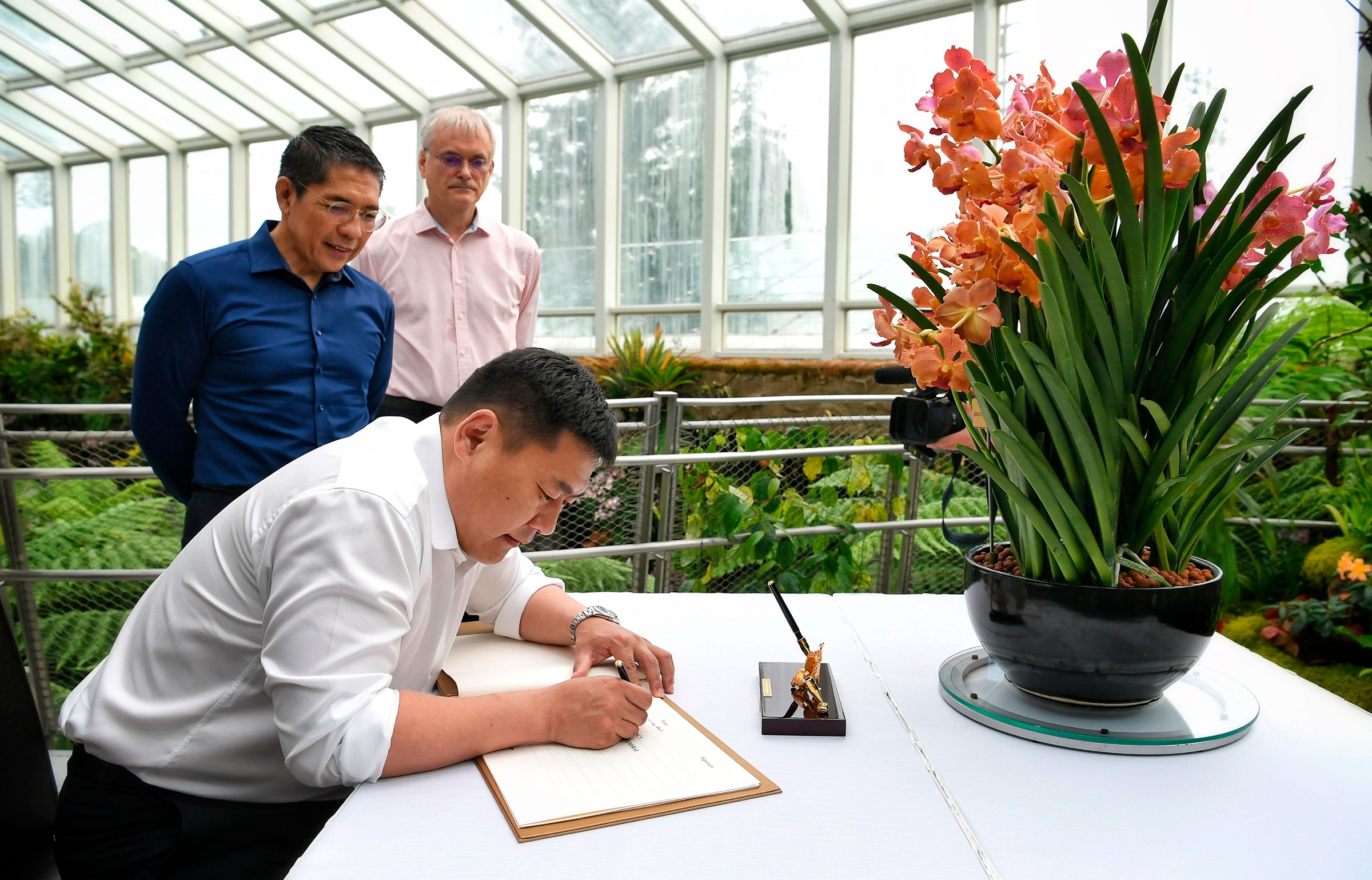

Oyun-Erdene is keen to emphasize his country’s openness to the world. He’s just returned from Singapore, where he discussed listing Mongolian mining firms on its bourse. Before that, he was talking about digital transformation in Estonia and human resources in South Korea. U.N. Secretary-General Antonio Guterres visited Mongolia on Aug. 8. “We have full confidence in our cooperation with our third neighbors,” the prime minister says.

Yet, in the current geopolitical climate, the approach is becoming tricky. Mongolia abstained from the U.N. General Assembly motion to condemn Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and voted against expelling Moscow from the U.N. Human Rights Council.

With regard to “the Ukraine and Russia war, we are truly regretful, and we have sent humanitarian assistance to Ukraine” Oyun-Erdene says. “But the foreign policy of Mongolia must remain independent. We believe that countries on the U.N. Security Council—major, big economic powerhouses—must come to decisions free from emotional distractions and be pragmatic, because every decision hugely affects the global economy and lives of millions.”

The bottom line? “Relations with our two neighbors is the priority.” The painted warrior on his office wall may be going to battle, but Oyun-Erdene’s fight will be to stay nonaligned.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Charlie Campbell at charlie.campbell@time.com