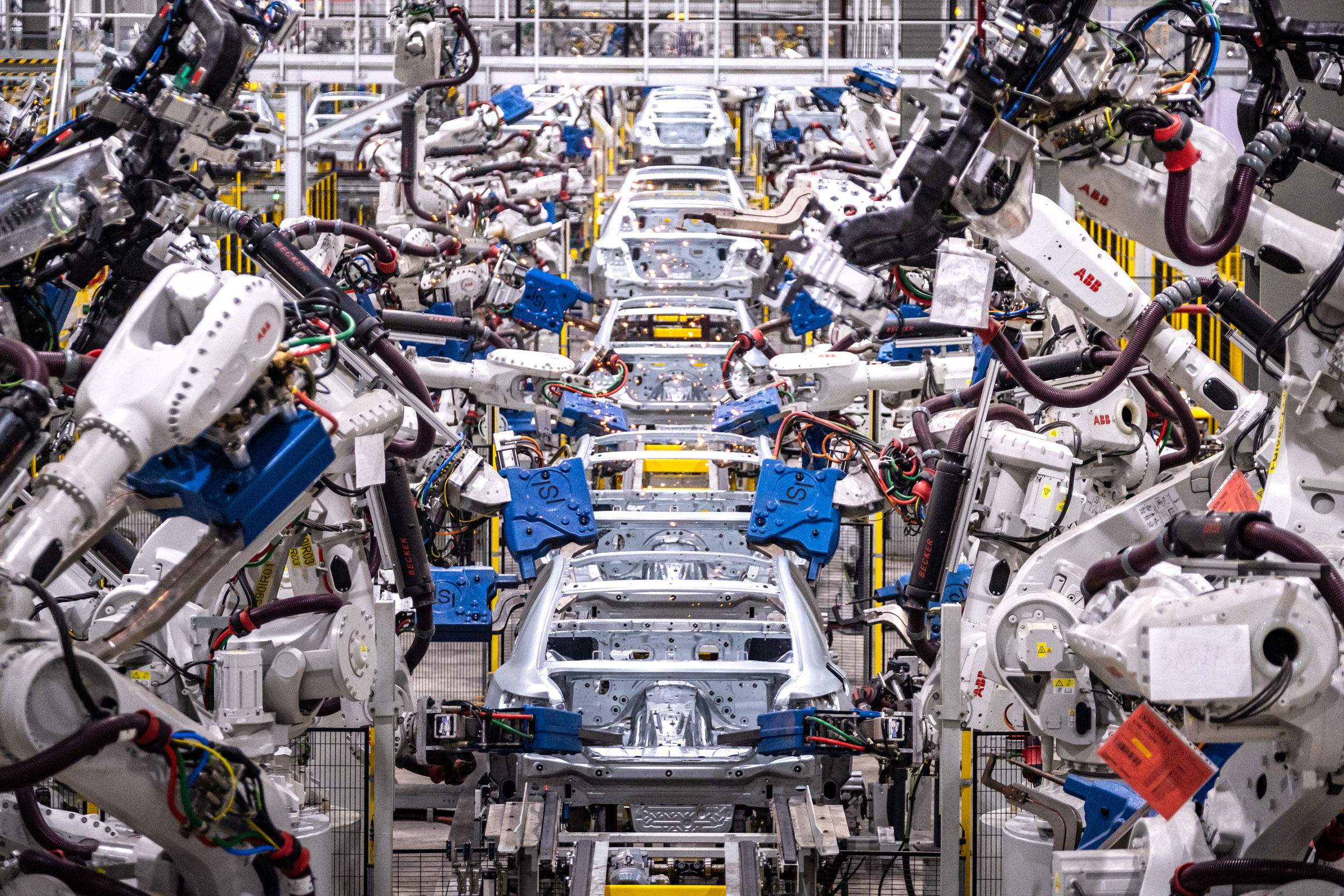

On northern Vietnam’s Red River Delta, the world’s most ambitious electric-vehicle (EV) upstart occupies a factory complex fringed with mango trees and palms. Outside VinFast’s plant by the port city of Haiphong, fishermen in conical hats still plumb mudflats for grass carp and tilapia; inside, each car negotiates an overhead ergonomic conveyor assembly line measuring 2.5 miles. A gauntlet of 1,250 robot arms twirl like pneumatic ballerinas, adding some 3,000 components and wielding rivet after rivet in a flurry of sparks.

Everything here is top of the line: machinery sourced from Germany, Japan, Sweden. Welding is 98% automated. Capacity is 250,000 cars a year. Impressively, instead of individual assembly lines tailored for each vehicle, the facility can simultaneously assemble multiple models on the same line. Even more impressively, Google Maps shows half of the 877-acre site sits beneath the South China Sea—a quirk because it was reclaimed from the waves and made operational in just 21 months.

Read More: The Biden Administration Is Trying to Kickstart the Great American Electric Vehicle Race

VinFast CEO Le Thuy likes to joke that not even the Mountain View, Calif., behemoth can keep up with the EV maker’s lightning pace. “At the start, everybody said that building cars in two years was impossible. Some even called us crazy,” she says. “But we launched three car models in those 21 months.”

The global EV market was valued at $185 billion in 2021 and is expected to rise by 24.5% annually to reach $980 billion by 2028. VinFast is not alone in craving a slice of that pie and is aggressively targeting the U.S. and European auto markets. To succeed, it needs to either unseat Tesla or persuade gasoline-car drivers to switch over. That’s no small feat: China accounts for about half of the global market for EVs, yet still none of its firms have tried the U.S. despite plowing tens of millions of dollars into feasibility studies.

Skepticism is natural when it comes to the congested global EV industry. No sooner does one startup steal a march on rivals than its latest funding round burns up and another overtakes it. Today, the U.S. industry has consolidated behind Tesla—worth some $750 billion and turning its co-founder, Elon Musk, into the world’s richest man—and legacy automakers are belatedly turning to a market whose importance is soaring alongside global oil prices. But how does a parvenu from the technological backwaters of Vietnam seriously expect to compete?

It’s a huge challenge. But VinFast’s parent VinGroup is no ordinary firm. Controlled by Vietnam’s richest man, Pham Nhat Vuong, VinGroup is the country’s largest conglomerate, with a total market value of $24.4 billion. Its 2020 revenue accounted for 2.2% of national GDP, and its reach is staggering. “It’s a remarkable story,” says Huong Le Thu, principal fellow at the Perth U.S. Asia Centre and adjunct fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. “There has never been anything of this size in Vietnam. It’s overwhelming at one level because now you can do everything with VinGroup.”

It’s almost a state within a state, at least for the upscale. A well-to-do Vietnamese can be born in a VinMec hospital, study at a VinSchool, live in a VinHome, shop at a VinCom mall, graduate from VinUni, vacation at VinPearl resorts, and, perhaps, become one of the leviathan’s 40,000 employees.

And now, they can commute in a VinFast electric car, EVs having emerged as the vehicle for the firm’s ambitions to leap from domestic to international. In June 2018, VinFast purchased a GM factory outside Hanoi and, by licensing intellectual property from GM and other auto giants like BMW, began producing its first gasoline VinFast vehicles less than a year later. These initial offerings were essentially ciphers of Western brands—specifically a Chevrolet Spark compact and a BMW 5 Series sedan and X5 SUV. Because of clever marketing and low costs, they proved immensely popular, capturing 17% to 19% of each market segment’s share domestically. They were also essential learning steps.

Beginning in August, VinFast will switch to exclusively manufacturing EVs. The company is also set to build a $4 billion factory in North Carolina and is scouting for a European plant. The 2,000-acre site in Chatham County plans to start by producing 150,000 electric vehicles annually beginning in July 2024, creating 7,500 jobs. It’s the largest single foreign direct investment in the state’s history and indicative of the scale of VinFast’s ambition, which is “to become one of the top global EV makers in five to 10 years,” says Thuy, also a deputy chairperson of VinGroup. “We think that we can be as good as anybody in the world.” On July 14, VinFast opened its first six overseas showrooms in California, including a flagship store in Santa Monica. Its first two models set for the U.S. market are sleek-looking SUVs, the VF8 and VF9. “It’s a solid car, no rattles or anything that would indicate a problem,” says Michael Dunne, founder of the ZoZoGo EV market intelligence firm, after a test drive. “But the U.S. market is not for the fainthearted.”

Read More: Lithium Is Key to the Electric Vehicle Transition. It’s Also in Short Supply

VinFast wants to entice American EV shoppers with a unique proposition: a 10-year warranty and a sticker price that doesn’t include the cost of the battery—an EV’s most expensive component. Instead buyers will have the option to lease batteries from the company for a small monthly fee. Once the battery life degrades to 70%, Vin-Fast swaps in a new one, free of charge. “Investors really like this kind of business-model story,” says Yale Zhang, an auto-industry analyst based in Shanghai. “The question is you need to source more batteries to make it work.”

It’s a bold play in an extremely competitive field. But despite VinFast’s inexperience and lack of core technologies, it has much deeper pockets than many new entrants into the EV market. VinGroup has so far plowed $6.6 billion into VinFast and assembled a leadership team headhunted from firms like Ford, Renault, GM, and BMW. The styling is by Italy’s Pininfarina; the dashboard displays by LG; the batteries by Samsung. “We leased IP from BMW, and so that immediately became the standard we worked to,” says Shaun Calvert, VinFast deputy CEO in charge of manufacturing, formerly with GM.

The firm also has some rather influential champions. In late March, President Joe Biden tweeted that VinFast’s U.S. investment plans were “the latest example of my economic strategy at work.” Within days, VinFast says, it had almost 10,000 preorders from customers in the U.S. “We keep joking that President Biden is the best salesman that we’ve ever had, and we didn’t have to pay,” says Thuy. It doesn’t stop there. When Thuy attended the SelectUSA investment conference in late June, she was delighted when most of a five-minute speech by U.S. Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo was dedicated to VinFast. “I’m amazed by the level of support that we’ve received from the U.S. government,” Thuy adds.

VinFast’s American adventure dovetails with the economic and geostrategic priorities of Hanoi, which aim to turn Vietnam into an upper-middle-income economy by 2030 and a high-income economy by 2045 by enhancing advanced manufacturing -capabilities. Already, most of the Samsung Galaxy smartphones sold in the U.S. are assembled here. But rather than rely on foreign companies, the priority among Hanoi politicians is to build strong local champions. “They want companies like VinGroup to take the lead in the national economy,” says Le Hong Hiep, a senior fellow at the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute in Singapore.

At the center of this ambition sits Vuong, the oldest of three children who grew up poor in Hanoi with his mother running a tea stand and his father serving in the Vietnamese army’s air-defense division. His talent for math led to a scholarship to study engineering at Moscow Geology University. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, he moved to Kharkiv, where he set up a Vietnamese restaurant. But soon he diversified into instant noodles flavored with spice blends from his homeland, eventually exporting from Ukraine to 29 countries. Fortune swiftly followed. Today, the brand he founded, Mivina, remains synonymous with noodles in Ukraine, like Xerox for photocopying in the U.S. In 2010, Vuong sold his company to Nestlé for a reported $150 million, returning to Vietnam ready for a fresh challenge.

His first domestic venture was a VinPearl beach resort on Hon Tre Island off Nha Trang. A flurry of plush real estate developments followed, including Ocean Park, a complex of 45,000 villas and apartments around an artificial sand and seawater beach in central Hanoi. Today, VinGroup boasts 27 urban complexes and 83 shopping malls across Vietnam. Vuong developed a reputation for bold business decisions and pivoting quickly. VinGroup nixed a foray into airlines in January 2020 as the pandemic took hold; Vuong repurposed a factory to make low-cost ventilators.

VinFast’s overseas expansion also provides protection for Vuong, whose elitist, capitalist Vin empire chafes with some of the ruling Communist Party’s old guard. In 2019, Vuong’s younger brother was sentenced to three years for bribery, and a purge of wealthy tycoons has gathered pace since, mirroring a similar campaign in China. “If he is successful overseas, and especially in the U.S., that will strengthen Vuong’s bargaining power in Vietnam and enhance his political status,” says Hiep.

Known for shunning the limelight and demanding high standards, Vuong is also a champion of women in a region where sexism is notoriously rife, especially in business. Four of VinGroup’s six vice chairpersons are women, including Thuy, who joined VinGroup from the now defunct Lehman Brothers investment bank, where she was vice president covering Asian markets. Asked about Vuong’s leadership style, Thuy replies, “Vision, strategy, discipline, and a lot of humanity … We only do things that have a big social impact.” For Huong, he’s “one of those visionary entrepreneurs. Maybe you could compare him to a Vietnamese Elon Musk.”

It’s an obvious comparison given Vuong’s increasingly laser-like focus on EVs. In December 2019, VinGroup sold off its VinMart chain of convenience stores. Last May, VinGroup announced the shuttering of its consumer-electronic arm, VinSmart, despite having secured 17% of the domestic smartphone market by then and marketing four models in the U.S. through AT&T. Instead, the conglomerate said it wanted to “mobilize all resources” into VinFast.

As the pandemic rumbled on, with borders closed and even domestic tourism curtailed, the group’s VinPearl resort on Hon Tre Island became an engineering hub. Over a thousand VinFast engineers and their families were ensconced on the island from May to October 2021 to work together uninterrupted 24/7. “At least we had the golf course to occasionally play on!” says Hoang Vu Nguyen, VinFast chief deputy of power train and a Ford veteran. It was here the differences of VinGroup’s working style became apparent. Rather than waiting for layers of local, regional, and international management to greenlight decisions, “as a chief deputy, I have direct communication with our CEO. The approval layer is almost flat.”

It is, of course, symbolic that Vuong’s first venture since returning from Ukraine became the hub for his new foray overseas. Given Vuong’s ties with both Russia and Ukraine, his perspective on Vladimir Putin’s Feb. 24 full-scale invasion has been subject to much conjecture. Vuong, who declined an interview request, has not commented publicly on the war in Ukraine, though a close confidant says he is “heartbroken.” Retaining deep ties with both nations, Vin-Group has helped arrange visas for Russians who have faced European travel restrictions.

Vuong’s discretion mirrors that of Vietnam’s government, which has long rooted its security in maintaining relations with all great powers, and is especially wary of enraging the Asian superpower to its north. For Vietnam’s leaders, Putin’s invasion of Ukraine was seen as “validation of their approach to China,” says Alexander Vuving, a professor at the Asia Pacific Center for Security Studies in Hawaii. For Hanoi, the lesson of Kyiv’s flirtation with the West was that it jeopardized the nation’s sovereignty and security. “They know their position next to China is very similar.”

Read More: The Cost Is Quickly Rising for China’s Embrace of Putin

Still, that neutrality has been buffeted by the invasion. Vietnam still purchases around 80% of military hardware from Russia, and it abstained on the U.N. motion to condemn Russia’s invasion. Yet it is an uncomfortable position for Vietnam’s leaders, and investments like VinFast’s North Carolina factory that build goodwill in the U.S. Congress offer a welcome counterweight.

VinFast’s U.S. investment “serves the geopolitical objectives of Vietnam, which is to cooperate with the U.S., boost ties, and balance trade,” says Vuving. A touted U.S. IPO for VinFast, for one, is possible only with the explicit approval of the Vietnamese Communist Party. “The Vietnamese government has been super supportive,” says Calvert.

Geopolitics underpins the U.S. position too. As Washington’s relations with Beijing enter a deep freeze, the White House is keen to cement ties across the Asia-Pacific—even though, politically at least, China and Vietnam are very similar beasts: regimes ruled by communist parties with scant respect for rule of law or human rights. Vietnam currently holds at least 208 political prisoners, according to the 88 Project, a rights watchdog that has documented “a concerted crackdown on dissent that has worsened in recent years.”

A key difference, of course, is that China’s ambitions on the global stage present a direct challenge to U.S. hegemony. President Xi Jinping’s avowed desire to reclaim “center stage in the world” undermines American interests from Europe to the Pacific, Latin America to Africa, most egregiously spotlighted by his backing of Putin’s invasion. On Feb. 4, the House of Representatives passed the America COMPETES Act to better challenge China technologically, economically, and diplomatically. “If you’re Xi Jinping, you have to make the world safe for autocrats,” one top State Department official tells TIME.

Any geostrategic ambitions Vietnam harbors are reserved for its own neighborhood, chiefly retaining influence in Laos and Cambodia. “China is competing strategically with the United States; Vietnam is cooperating strategically with the United States,” says Vuving. Vietnam also frequently clashes with Beijing over disputed islands in the resource-rich South China Sea, and memories of China’s ill-fated invasion of 1979 burn brighter than those of American misadventure in the region. Today, approval of the U.S. among Vietnamese stands at a staggering 84%.

It is comfort born of knowing its place in the world. While China’s leaders leverage the “century of humiliation” wrought by colonial powers to justify a resurgent and toxic nationalism, Vietnam has no such baggage; over the past century, this plucky nation has bested French, American, and Chinese invaders. Vietnam is under no illusions about who it is: the toughest, scrappiest little guy in a rough neighborhood. But can its premier company compete with the might of Tesla? Given the scale of the nascent EV market, it might not have to. “The real competition of EVs like VinFast are not Tesla,” says Stephanie Brinley, principal analyst at S&P Global Mobility. “The real competition is internal combustion engine owners, getting those guys to jump on board.”

VinFast and Vietnam are confident that they can. On a cruise for VinFast investors tracing the jagged limestone karsts of northern Vietnam’s Ha Long Bay, a musician in silk ao dai strums a whining version of the Eagles’ “Hotel California” on the single-stringed zither, as a DJ cranks up a thumping bass track. It’s a scene that telegraphs where this Southeast Asian nation now wants to be: a business-friendly, tech-savvy industrial powerhouse. The next South Korea, if you will, an ambition that feels explicit, given the DJ’s K-pop-inspired peroxide mop. “A lot of people in Vietnam take pride in VinFast, and they want to support the project, and they want us to be successful,” says Thuy. To electrify America’s “dark desert highway” with Vietnam’s red star.

—With reporting by Eloise Barry/London

Correction, July 25

The original version of this story misstated the two models that VinFast will initially sell in the U.S. They will be the VF8 and VF9, not the VF7 and VF8.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Charlie Campbell/Haiphong, Vietnam at charlie.campbell@time.com