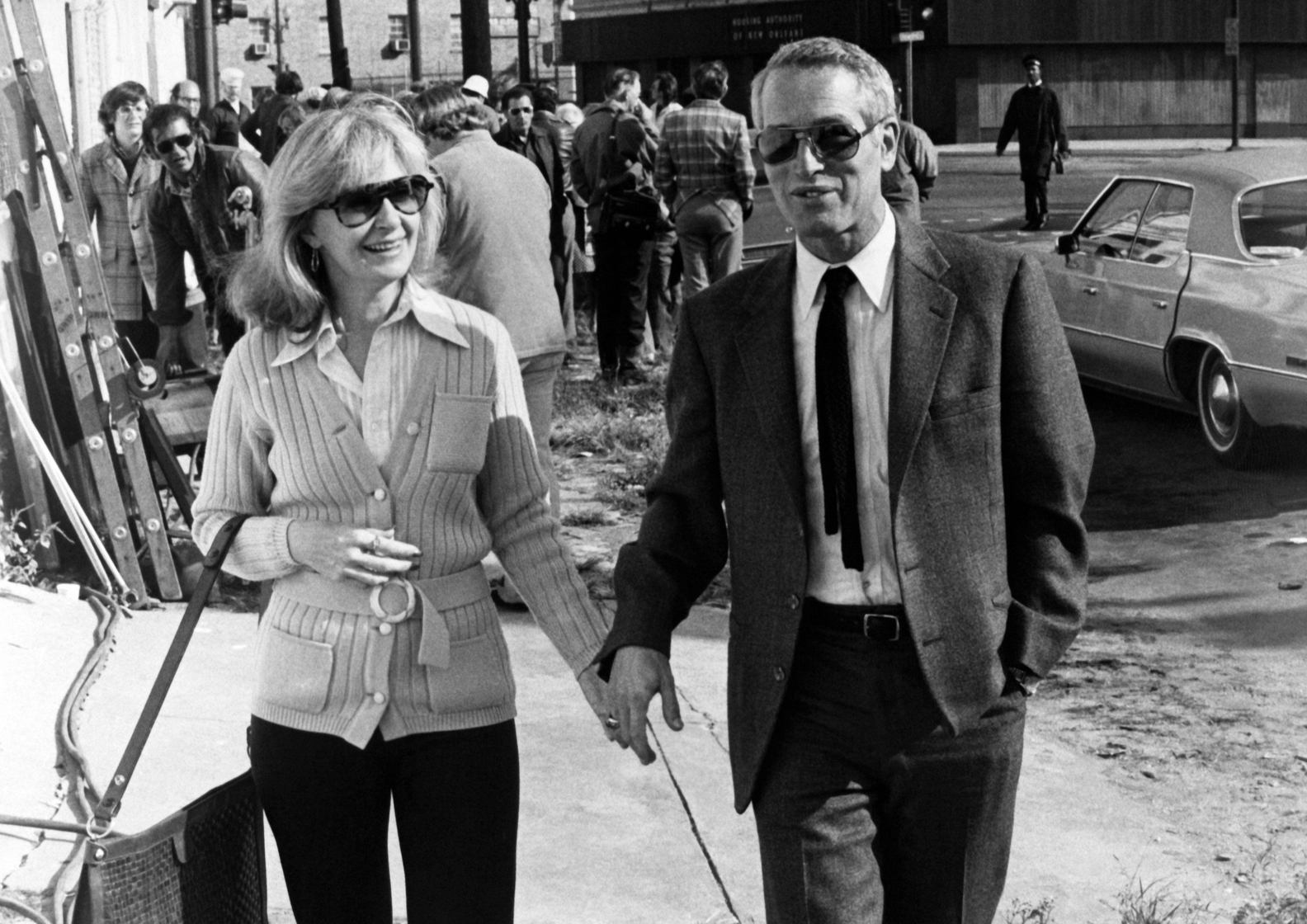

If you think Paul Newman is the coolest, Ethan Hawke’s superb multi-part documentary The Last Movie Stars is for you. And if you only sort-of know the work of his wife, Joanne Woodward, The Last Movie Stars is absolutely for you, for two reasons. To understand Newman as both an actor and a man, you need to know something about the woman whose influence helped make him one of the most charismatic performers of the late 20th century. But there’s something else: Woodward was one of the finest actors of her era, but for various reasons—being a mother to six children chief among them—she never had the big Hollywood career she deserved, even though she was a star before most people knew who her husband was. The story of Newman and Woodward is one of the great Hollywood stories, as distinguished from a great Hollywood romance: their partnership was so distinctive, so whole, and at some points so rocky, that to sentimentalize it only does it a disservice.

Hawke has deep affection for these two performers, as stars and as people. But if The Last Movie Stars, airing on HBO Max, is a work of great warmth, Hawke easily steers clear of turning it into hagiography. Hawke was approached by Woodward and Newman’s surviving children, who wanted to ensure that their parents’ work, and their extraordinary but far-from-perfect life together, wouldn’t be forgotten. Hawke didn’t know the couple personally, but as a teenager in New Jersey, he would sometimes see them around his school, which one of their children attended. To him, they seemed the model husband-and-wife team, two working actors who had built a seemingly idyllic partnership. The Last Movie Stars explores both the truth and the fallacies behind that image, and even though several of the Newmans’ surviving children appear in the documentary, speaking candidly about their parents’ flaws as humans, Hawke shapes it all into a voyage of exploration, not of muckraking. Illustrated with film clips and archival footage that breathe life into the story, this is a portrait of two people who loved their craft and each other, in almost equal measure. It’s also a reminder that marriage isn’t for the faint of heart—and even those unions that look great from the outside always carry their share of heartache.

The Last Movie Stars consists of six episodes, each one running roughly an hour. That’s a lot of Newman and Woodward. But once you start digging in, you realize this thing could almost stand to be longer, particularly given the way Hawke frames the material. The backbone of The Last Movie Stars is a vast set of interviews with key players in Newman’s life and career, conducted by Rebel Without a Cause screenwriter Stewart Stern. Newman had originally intended to use the interviews to write a memoir, only to change his mind; in 1998, 10 years before his death, he burned the tapes. (Around the same time, he burned his tuxedo in the driveway of the family’s Connecticut home, which tells you something about his relationship to fame.) Fortunately, Stern had had the tapes transcribed, and so the voices of the people who worked with or were close to either Newman, Woodward or both—among them Sidney Lumet, Martin Ritt, Gore Vidal, and Newman’s first wife, Jackie Witte—survived on paper, at least. For Hawke, The Last Movie Stars was partly a pandemic-era project, and so he gathered friends, colleagues and family members via Zoom to talk about Newman and Woodward and their dual legacies. Stern’s transcripts are brought to life by some of Hawke’s fellow actors: Laura Linney reads the words of Joanne Woodward, and George Clooney gives voice to Newman’s.

If Hawke’s method is complicated to describe, the result is wholly engaging and intimate. (Hawke has a gift for making offbeat, exhilarating documentaries: his 2014 Seymour: An Introduction, a portrait of New York piano teacher Seymour Bernstein, traces the inherent meaning of creativity in everyday life.) The Last Movie Stars dips and swerves between Newman and Woodward’s personal and professional lives, noting the points of disharmony as well as accord. The two got to know one another while working on the Broadway production of Picnic in 1953. Newman was required to dance onstage and didn’t know what he was doing; Woodward, an understudy, stepped in to help, and the duo’s relationship—which, they themselves make clear, included a bang-up sex life—took flight, even though Newman was married at the time, to Witte.

Those who like their true-love life stories clean and tidy should brace themselves: Newman and Woodward were nearly five years into their union when Newman finally left Witte, shortly after the birth of Witte and Newman’s youngest child, Stephanie, who speaks frankly on-camera about how much Newman’s deceit damaged the family and hurt her mother. (Newman’s son from that first marriage, Scott, died from a drug overdose in 1978.)

But Stephanie also has Joanne Woodward tattooed in flowing script on her forearm. Because if, as this documentary reveals, Newman was often remote and disconnected—both with his children and with Woodward, the love of his life—it was Woodward who held the extended family together, coming to love Newman’s first three children as much as she loved the three that she and Newman had together. Newman, who from the beginning looked celestially beautiful onscreen, and who learned to become a terrific actor after a rocky start, wasn’t always the best father. But it’s entirely possible that Woodward, who put her own career on hold to do her best by six children, was the more innately gifted actor. In several clips culled from talk-show interviews of the 1970s and ‘80s, Woodward speaks with daring forthrightness—for that time, or for this one—about the cost of what she gave up, despite how much she loved her children.

Though The Last Movie Stars is fantastically revelatory about this couple’s life together, which they took great pains to keep private during their 50-year-marriage, it’s still the movie clips that tell the most important part of the story. Newman was a dazzling screen presence in pictures like Hud, Cool Hand Luke, and The Verdict, to name just three of many. In some of these performances, he radiates an earthy carnality; in others, he betrays the universal insecurities and doubts of the aged, of people who may know in their hearts they didn’t do as well as they could have by those around them.

Woodward was a different kind of actor, and her career took a wholly contrasting shape. Her big successes came early: she won an Oscar long before her husband did, for her role in The Three Faces of Eve, released in 1957. In the movies she made in her youth, like The Sound and the Fury and The Long Hot Summer, as well as the later TV-movie roles she took on when those constituted the only work she could get, she always seemed to glow from within, and her voice was the equivalent of a seashell’s pearlescent interior. As her husband did, she worked at her craft. (Both had studied with Method guru Sanford Meisner.) But her spirit, animated by her own innate sexual electricity, was the wellspring of all she brought to bear onscreen or onstage.

Read more reviews by Stephanie Zacharek

In one of The Last Movie Stars’ most revealing moments, we hear Newman’s voice, channeled through Clooney’s, reflecting on his status as a sex symbol. He barely understood his own charisma, because he was, by his own admission, a man who had trouble knowing himself. It was Woodward, he says, who drew out his most resplendent qualities and empowered him to share them with the world. To watch scenes from her movies is to see that truth played out wordlessly, in her glorious, tremulous vitality. Newman died in 2008. Woodward is still alive, having been diagnosed with Alzheimers in 2007. The duo made 16 films together, the final one being James Ivory’s 1990 Mr. and Mrs. Bridge. Taken alone, Newman remains one of the most ravishing sexual beings the movies have ever given us. But the aura that lingers around Woodward is the eternal witchery of springtime, fierce and delicate at once. To explain her as a performer, to describe her adequately, would demand another six-hour documentary. As it is, she shares this one. But you come away knowing who really has top billing, written in invisible yet obvious ink.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com