In the three months since Russia invaded Ukraine, the conflict has left little doubt of the power of disinformation—about the past as well as the present. Russian President Vladimir Putin has justified his “special military operation” with a distorted version of Ukrainian history and with false claims that Ukraine’s present-day leaders are “Nazis.” Now, with the West aware of how Russian aggression has played out in places like Irpin and Bucha, we are also watching a struggle unfold over the legacy of the Nuremberg Trials. Ukrainian leaders are looking to Nuremberg to demand a full investigation into Russian war crimes. At the same time, Russian leaders have invoked Nuremberg to justify their invasion of Ukraine, a reminder of how history and the law can be manipulated to serve almost any end.

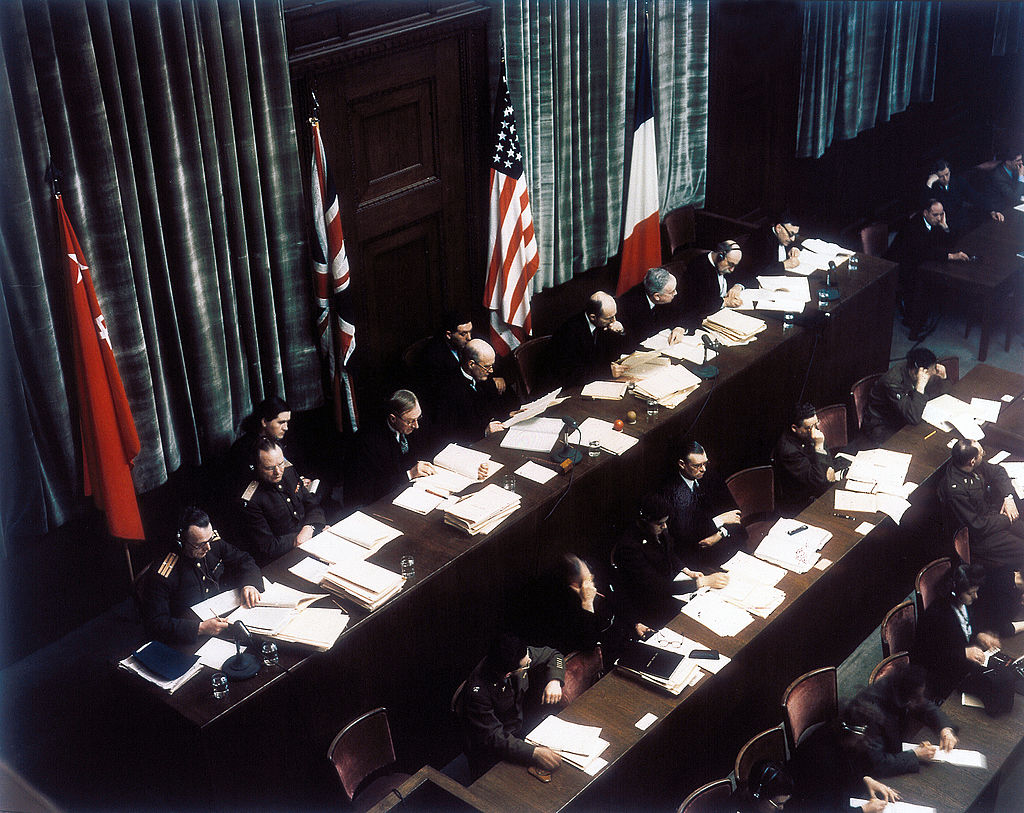

In November 1945, the United States, Great Britain, France, and the Soviet Union convened the International Military Tribunal at the Palace of Justice in Nuremberg, Germany, to try 22 former Nazi leaders for conspiracy, crimes against peace, war crimes, and crimes against humanity. Those in the dock included the members of Hitler’s inner circle as well as Germany’s military leaders, government ministers, and propagandists; the vast majority of those tried were convicted.

The decision to organize an international tribunal after World War II was prompted by a desire on the part of the Soviets as well as the Americans to hold Nazi leaders criminally responsible for launching an aggressive war. It was the Soviets who first proposed such a tribunal, and a Soviet lawyer, Aron Trainin, who coined the term “crimes against peace.” Lawyers from the U.S. War Department’s Special Projects Branch such as Murray Bernays embraced the idea—as did U.S. Secretary of War Henry Stimson. After the victory, the new U.S. President Harry S. Truman quickly came on board; British and French leaders soon followed.

Read more: How the Meaning of ‘War Crimes’ Has Changed—And Why It Will Be Hard to Prosecute Russia for Them

Nuremberg had its critics from the start. Even before the verdicts were in, some lawyers and journalists dismissed the tribunal as “high politics masking as law.” After the trials, the French judge Henri Donnedieu de Vabres revealed that he had keenly felt the criticism of the Nuremberg judgment for having been decided only by representatives of the victors. De Vabres argued that this could be remedied for the future with the creation of a permanent international criminal court.

Plans to create this international criminal court stalled during the Cold War. Instead, Nuremberg became a linchpin of competing national mythologies about World War II and postwar justice. In the United States, the war and Nuremberg were remembered as triumphs of Western leadership and liberal values. In the Soviet Union, Nuremberg symbolized the Soviet victory over German fascism and the emergence of the USSR as a world power.

The Cold War is over and we now have an International Criminal Court. But the court has failed to become all that de Vabres had envisioned, largely because key states like the United States and Russia refuse to accept the court’s jurisdiction. The idea of Nuremberg, meanwhile, lives on—and has taken on fresh meaning for two successor states of the Soviet Union: Russia and Ukraine.

For Ukraine, Nuremberg means hope—the possibility of bringing Russia’s leaders to justice for waging an illegal war of aggression. Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky has been calling for a new Nuremberg since April 5. International lawyers and policymakers from Ukraine, Lithuania, Great Britain, the United States, and many other countries have joined him—and have put forward resolutions, proposals, and model indictments for such a tribunal. They have reminded the world that the Nuremberg judgment deemed aggressive war “the supreme international crime.”

Read more: How Ukraine Is Crowdsourcing Digital Evidence of War Crimes

This turn to Nuremberg as a model and inspiration has been prompted in part by practical considerations. Ukrainian courts can try Russian soldiers for war crimes—and in fact, the first war-crimes sentencing of a Russian soldier took place on Monday in Kyiv. The International Criminal Court can try Russian leaders for genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity that take place in Ukraine. But it cannot try Russian leaders for launching an aggressive war, because Russia is not a state party to the Rome Statute of 1998. For that Ukraine needs Nuremberg.

Nuremberg also has great symbolic significance for Ukraine, which endured a brutal occupation by Nazi Germany during the Second World War. Some of the same towns and cities that were bombed and terrorized by Nazi occupiers in the 1940s—including Mariupol, Kyiv, and Kharkiv—are once again the site of devastation and mass atrocities.

Meanwhile, Putin has been invoking Nuremberg to rally the Russian people for the war against Ukraine. He has promulgated the lie that Ukraine is being run by Nazis—and has repeatedly made a false connection between Ukrainian nationalist organizations that collaborated with the Germans during World War II and Ukraine’s leaders today. Since the invasion on Feb. 24, he has defined his goal as Ukraine’s “de-Nazification.”

Read more: Historians on What Putin Gets Wrong About ‘Denazification’ in Ukraine

Russian leaders and propagandists have put forward proposals for Ukraine’s “de-Nazification” that include trials of Ukrainian leaders and soldiers. One such plan, published by the state news agency RIA-Novosti in April, proclaimed that by convening a public tribunal, Russia would “act as the guardian of the [legacy of the] Nuremberg Trials.” On May 10, Russian State Duma member Andrei Krasov called for a “Nuremberg 2.0” to try Zelensky and other Ukrainian leaders, whom he falsely smears as “neo-Nazi killers.” Last week Russian officials denounced the Ukrainian soldiers who surrendered at Azovstal as “Nazi war criminals” and called for a public tribunal in Donetsk to provide “a lesson for everyone who has forgotten the lessons of Nuremberg.”

What are these “lessons of Nuremberg” that Russian leaders and propagandists want to linger on? There is the obvious lesson that Nazism is evil. But there are other “lessons” that are based on a patriotic-nationalistic history of World War II. In this narrative, the Russians are the saviors of Europe and the main victims of the Nazi genocide. They cannot be perpetrators or fascists: these labels are reserved for the Nazi invaders and their accomplices. This narrative of World War II is protected by a 2021 Russian memory law that bans public discussion about Soviet collaboration with Nazi Germany or about Soviet war crimes during World War II—a memory law that purports to be based on “the Nuremberg verdict.”

Putin looks to the Nuremberg verdict because the Soviet Union, as one of the victors, was not tried at Nuremberg for its own crimes against peace. Nor was it held responsible for any war crimes or crimes against humanity. No Allied crimes were tried at Nuremberg; the tribunal’s jurisdiction was limited to the crimes of the European Axis powers. But Putin is using the tribunal’s restricted scope to manipulate the past: for Putin, the fact that Soviet crimes were not judged at Nuremberg means that they never happened.

Read more: A Visit to the Crime Scene Russian Troops Left Behind at a Summer Camp in Bucha

Putin’s lies about the past and lies about the present go hand in hand. Present-day Russia is mired in disinformation about Ukraine, about the war, and about the perpetration of war crimes; Russian atrocities in Mariupol, Bucha, and other towns and cities are dismissed as “fakes” or falsely blamed on Ukrainians. This is one of the reasons that Ukraine’s call for a Nuremberg-like tribunal to hold Russia’s leaders accountable is so compelling. Such a tribunal, based on the collection and review of incontrovertible evidence, could bring Putin and those in his circle to justice and also set the story straight about the war.

Ukraine and its supporters can draw important lessons from Nuremberg’s achievements as well as from its flaws. A new international tribunal to try Russia’s leaders must affirm the illegality of aggressive war and reveal the connections between crimes against peace and other war crimes. At the same time, any tribunal established by Ukraine and its allies must avoid politicizing the prosecution of war criminals. It must work to establish a complete historical record; this is necessary for its own legitimacy and for the benefit of future generations. Above all, such a tribunal must remind the world that there are universal principles—and that those who violate them will be punished.

Of course, none of this is inevitable. History shows that it is the victor who gets to organize postwar tribunals. For Ukraine to bring Putin and his circle to justice, it will first have to win the war. There is also a dark alternative: a Nuremberg-type tribunal of Ukrainian leaders held by Russia. This would inevitably be a Soviet-style show trial—a kangaroo court that would degrade international law and could taint the meaning of Nuremberg forever.

Francine Hirsch, Vilas Distinguished Achievement Professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, is the author of Soviet Judgment at Nuremberg: A New History of the International Military Tribunal after World War II(Oxford, 2020).

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com