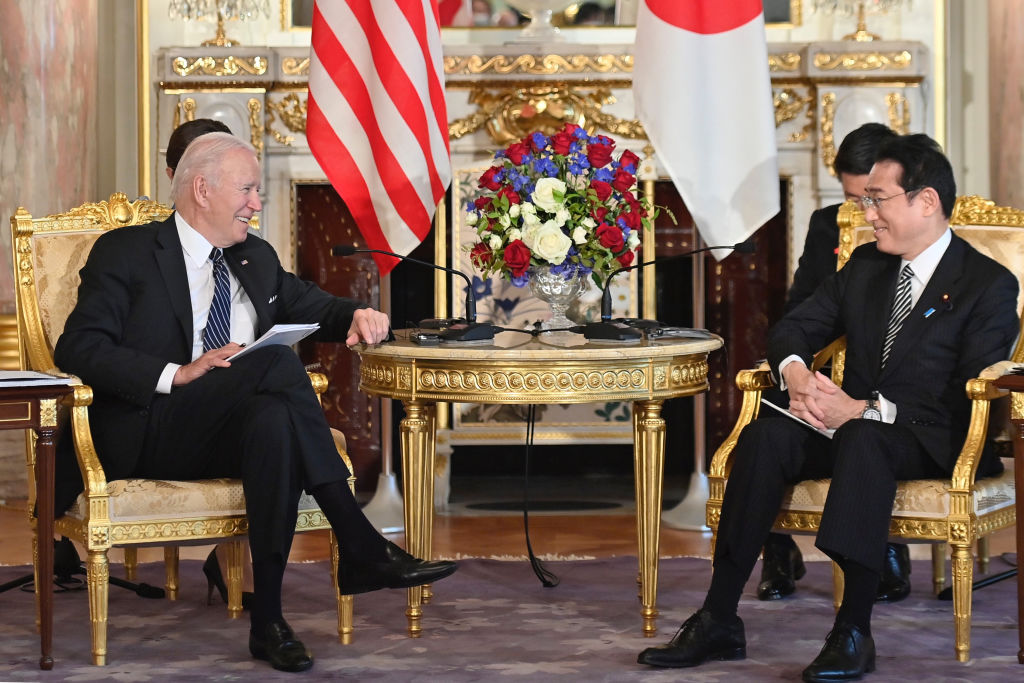

During his visit to Asia, which concludes May 24, President Joe Biden has been reiterating that his foreign policy is centered on uniting “partners who share our values” in order to oppose governments “who do not share our values.” To meet the challenges posed by a powerful and ambitious China, however, relying on common political values to build a coalition may be a costly blunder. This approach limits the number of potential U.S. security partners when Washington needs as many as it can get.

Biden’s most pressing task in the Asia-Pacific is to gather governments that will support the U.S. vision of a regional order over the Chinese vision. Only a handful of Asia-Pacific countries, however, are full-fledged liberal democracies. Many potential U.S. supporters and security partners are ambivalent if not hostile toward liberal values. That pool is growing as illiberalism is ascending and liberalism is declining in the region. Look no further than the Philippines, where the once-disgraced Marcos family has just returned to power.

Read more: The World Should Be Worried About a Dictator’s Son’s Apparent Win in the Philippines

Moreover, America’s ability to pass its own litmus test is increasingly in doubt. The U.S. is now classified as a “flawed democracy” (Economist Intelligence Unit) or a “backsliding democracy” (Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance). A Pew Research Center report in November 2021 found that respondents in each of 16 countries surveyed believed racial and ethnic discrimination are worse in the U.S. than in their own countries.

Washington already knows how to cooperate with states that do not behave according to liberal principles. To defeat Germany and Japan in World War II, the U.S. sided with Stalin’s Soviet Union, imperialist powers Britain and France, and a brutally authoritarian government led by Chiang Kai-shek in the Republic of China. During the Cold War, Washington supported “friendly dictators” against Soviet-backed dictators. The U.S. in recent years has had close security relationships with countries such as Turkey, Saudi Arabia, and Pakistan.

Conversely, Washington still maintains formal distance from Taiwan, which does share American political values. Taiwan is a liberal democracy with which the United States has a deep historical friendship, thriving economic ties, and shared security interests. Yet, Washington maintains no official relations with Taipei and offers no firm commitment to help defend Taiwan. The common-values principle is sacrificed in the interest of a constructive U.S.-China relationship.

Making an issue of the domestic political systems of potential partners impedes cooperation. In the late 1940s the U.S. government rebuffed overtures from Vietnamese revolutionary leader Ho Chi Minh, who feared Chinese domination, because Ho was “communist”; this contributed to Ho’s Vietminh entering a temporary semi-alliance with China.

Read more: How Long Will Joe Biden Pretend Narendra Modi’s India Is a Democratic Ally?

At an Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) summit in Malaysia in 1998, the then U.S. Vice-President Al Gore offended the host government and strained the bilateral relationship by praising Malaysian dissidents seeking political reforms. Washington’s disapproval of a 2014 military coup in Thailand led to a diminution of the U.S.-Thailand relationship and corresponding improvement in Sino-Thai relations. Similarly, the U.S. and other Western governments withdrew their support from Cambodian autocrat Hun Sen after he led a 1997 coup, putting Cambodia on a path of deepening integration with China. In 2021 the U.S. ended the last vestiges of U.S.-Cambodia military cooperation.

The Philippines is an especially instructive example. A U.S. treaty ally, the country is potentially a bulwark against Chinese attempts to establish quasi-ownership over the South China Sea. But U.S. relations with Rodrigo Duterte, elected president in 2016, soured after he objected to Washington’s criticism of his government’s large-scale extrajudicial killings of alleged drug traffickers. As a result, even as the Philippines won a landmark judgment by an international tribunal in July 2016 against China’s intrusion into Philippine maritime territory in the South China Sea, Duterte traveled to Beijing. There, he received red-carpet treatment as he announced his country’s “separation” from the United States and “realignment” with China.

“America has lost,” he said. “I will not go to America anymore. We will just be insulted there.” Duterte even announced he planned to abrogate the Visiting Forces Agreement with the United States that gives American soldiers special legal rights in the Philippines. He only recanted near the end of his presidency, because of continued Chinese territorial encroachment.

Washington is already hard-pressed in its competition with Beijing. China is the top trading partner of most countries in the region, giving Beijing strong political leverage. Asia-Pacific states know that geography makes China a permanent fixture, while America’s commitment to maintaining a leadership role in the region could change with the next U.S. presidential election.

The United States has taken on global responsibilities that often demand the diversion of U.S. resources to places other than Asia. The strategic friction points are in China’s front yard, while the United States most cope with long supply lines. China’s navy is larger than the U.S. Navy and it has a formidable network of weapons systems to fight U.S. armed forces in the western Pacific. Most pertinently, Beijing is famously indifferent to the internal political systems of the countries with which it does business; China establishes “strategic partnerships” with pariah states, liberal democracies, capitalist economies, and religious autocracies alike. The U.S. cannot afford to saddle itself with an additional disadvantage.

America’s self-defeating demand for liberalism

The question arises why the Biden Administration would want an approach that risks alienating possible security partners. It can be explained as a reassertion of the bipartisan, post-Cold War U.S. foreign policy outlook that prevailed prior to the downgrading of shared values during the Trump years. That longstanding outlook bears the influence of democratic peace theory: the notion that the global spread of liberalism makes war increasingly obsolete because democratic states purportedly don’t go to war against each other. From this standpoint, it is natural to emphasize promoting liberalism as the goal of security policy.

An unconscious Eurocentrism is also possibly at work here. Many senior American officials learned international relations by focusing on the experience of Europe during the Cold War, which tended to inculcate a binary worldview of democratic states (Western Europe) versus non-democratic states (Eastern Europe). These officials now awkwardly overlay this worldview upon the Asia-Pacific, failing to account for the region’s greater diversity compared to Europe.

Read More: Joe Biden’s Democracy Summit Is the Height of Hypocrisy

U.S. global advocacy of democracy, human rights and widely accepted international norms has made the world a better place. Liberal values will always be a component of US foreign policy, but they should not always drive it. Shared liberal values strengthen some of America’s closest alliances, but ultimately these partnerships are based on shared interests.

The fact of the matter is that few states in the region are, or even aspire to be, liberal democracies. But most fear the prospect of a muscular China at their doorstep. It is an appeal to this common interest, rather than a narrower set of common values, that will give Washington its broadest possible base for effective regional leadership.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Contact us at letters@time.com