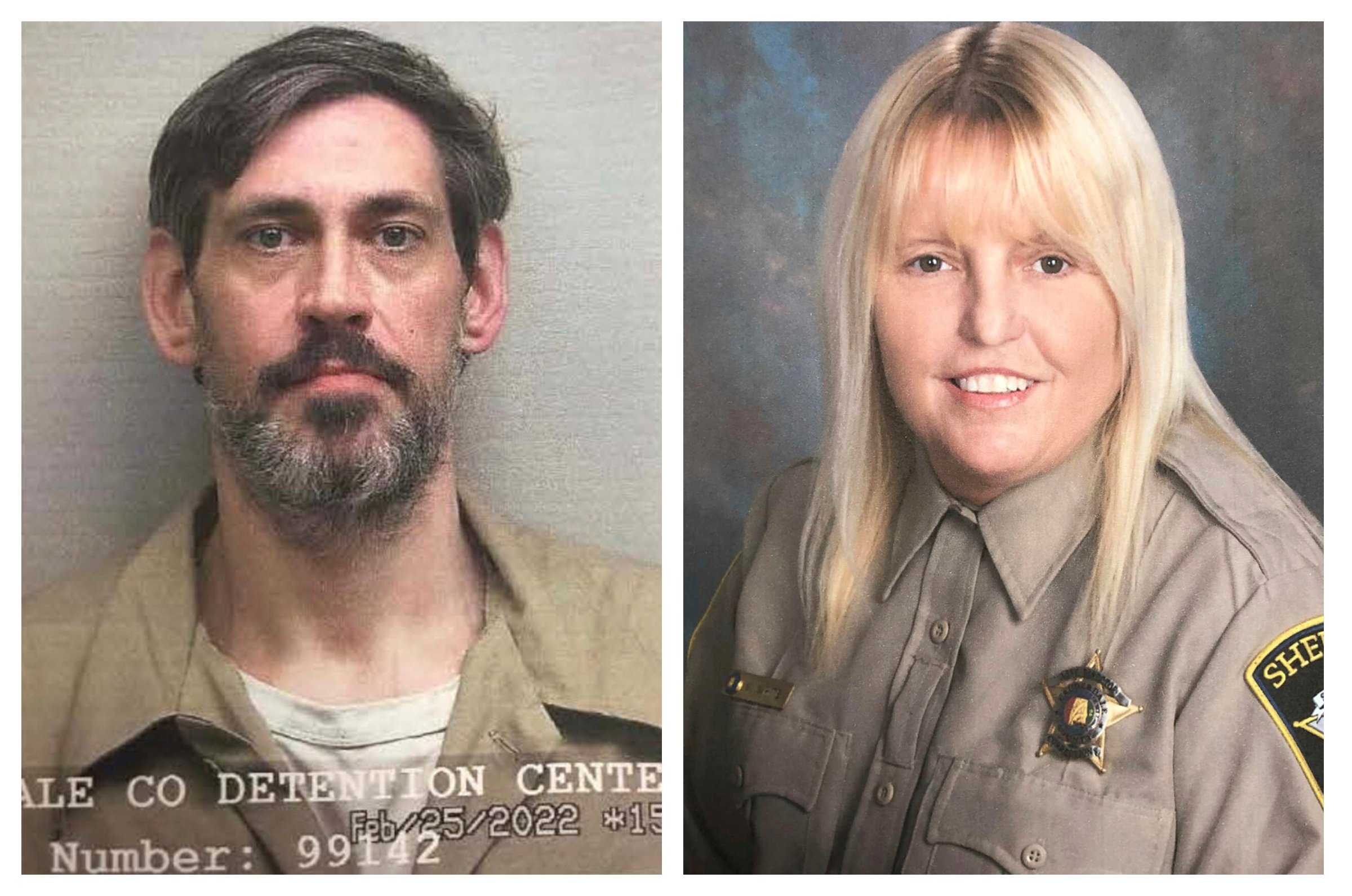

The seemingly made-for-TV story of the Alabama murder suspect who escaped from jail with the help of a female correctional officer after the two possibly became “romantically involved” ended in tragedy this week. Vicky White, the assistant director of corrections at the Lauderdale County Jail in Florence, Ala., died by suicide after she and fugitive Casey White were spotted by police in Evansville, Ind., authorities said.

The case became a sensation, drawing extensive TV coverage, partly because it is such an anomaly. Escapes are incredibly rare—an estimated 0.1% of prisoners escape custody. Those involving help from the inside are almost unheard of.

But Vicky White’s alleged relationship with Casey White also highlights a daily reality within jails and prisons across America: Inmates and correctional officers often form personal bonds because of the close nature of their environment. While such relationships can be healthy for incarcerated people, they are also ripe for abuse because the officers have inordinate control.

“One of the bigger difficulties with something like corrections is that there’s an important boundary that has to be established between inmates and [correctional officials] but it’s important to keep a human connection as well,” says Thomas Baker, an associate professor of criminal justice at the University of Central Florida. “You don’t want to treat [inmates] poorly but you don’t want to step over certain boundaries.”

Authorities said Vicky White helped Casey White to escape from jail on April 29 by falsely claiming that she was taking him for a court appearance. Lauderdale County Sheriff Rick Singleton said an investigation revealed that the correctional official was having a romantic relationship with Casey White, and other inmates complained that she gave him preferential treatment, including extra food.

Read more: The Conservative Case For Prison Reform

Sexual relationships between guards and inmates are illegal and are also considered abuse because inmates cannot legally give sexual consent due to the power correctional officers hold over them. While female prisoners suffer sexual assault and harassment by guards at higher rates than men, a 2014 U.S. Bureau of Prisons study found that female correctional staff committed more than half of all sexual assaults that were substantiated by investigators. The study found some 545 such cases between 2009 and 2011 across federal and state prisons and local jails. More than 90% of the victims were male inmates, and in 85% of cases investigators said the victims “appeared willing.”

One question this incident does raise is the oversight at the facility where Vicky White worked. Due to her status as a manager at the jail, she had the authority to transport inmates by herself. While it’s not clear whether staffing issues were a factor in this case, jails and prisons across the country are facing shortages of workers—leading to worries about oversight.

“Corrections in the United States right now is under humongous staffing issues. Everywhere is understaffed. There’s nowhere that has as many people as they would like,” Baker says.

Read more: COVID-19 Has Devastated the U.S. Prison and Jail Population

Vicky White, by all accounts, was beloved in the county she worked in. “The whole sheriff’s office is like family,” Singleton said at a press conference on May 9. “When you have a family member that makes a bad choice, you know, you don’t like them but you still love them. She was family to us. And so yeah, it hurts.”

After a nationwide manhunt, they were spotted at a Motel 6 parking lot 275 miles away in Evansville, Ind. on May 9. A car chase ensued, which ended in the two fugitives crashing their gray Cadillac. Authorities said Vicky White shot herself and later died at the hospital. Casey White was taken into custody, and is awaiting extradition back to Alabama.

“They thought they’d driven long enough. They wanted to stop for a while, get their bearings straight and then figure out the next place to travel,” Vandenburgh County, Indiana Sheriff Dave Wedding said at a press conference Tuesday.

According to authorities, the two had multiple semiautomatic weapons, including an AR-15 assault rifle, $29,000 in cash, and wigs. When Casey White was taken into custody he told police that he had been prepared to shoot at them.

“Escapes in and of themselves are rare when it comes to critical incidents in prisons and jails. To add on top of it, a staff member helping an inmate escape from custody is super rare,” Jeff Mellow, a criminal justice professor at John Jay College in New York City says. “The overwhelming majority of escapees are caught within the first month. In many ways, this escape fits into the pattern of typical escapes.”

In addition, the facility is small (it has a total population of 233 and books about 5,000 prisoners per year) which makes this type of escape easier.

“If we look at the type of facilities where individuals escape from, the majority escaped from small jails. They oftentimes are less secure, don’t have the type of perimeter fencing that maximum secure facilities have,” Mellow says.

Rare as escapes with the help of a correctional officer are, there is one relatively recent precedent. That case similarly drove huge attentions. Joyce Mitchell was convicted of helping two convicted killers, David Sweat and Richard Matt, escape an upstate New York prison in 2015 by sneaking in materials like guns, ammunition, a compass and camping gear for them to use to get out of the facility. Mitchell also had a romantic relationship with at least one of the inmates. The story became the basis for the Showtime miniseries Escape at Dannemora.

Casey White was already serving a 75-year sentence for multiple prior crimes. At the time he left the Alabama facility, he was awaiting trial on murder charges for a 2015 stabbing. If he’s convicted in that case, he could face the death penalty.

Baker, the Central Florida professor, hopes the tragic Alabama jailbreak does not dissuade jail and prison officials from maintaining social relationships with people incarcerated in prisons and jails.

“Correctional Officers are the people that come in contact with the incarcerated more often than anybody else. And so they can really help with the re-socialization process that’s supposed to take place in prisons and jails,” Baker says. “This could set up a perspective that there should be even less contact and more dehumanization of [inmates] and that’s problematic.”

If you or someone you know may be contemplating suicide, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255 or text HOME to 741741 to reach the Crisis Text Line. In emergencies, call 911, or seek care from a local hospital or mental health provider.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Josiah Bates at josiah.bates@time.com