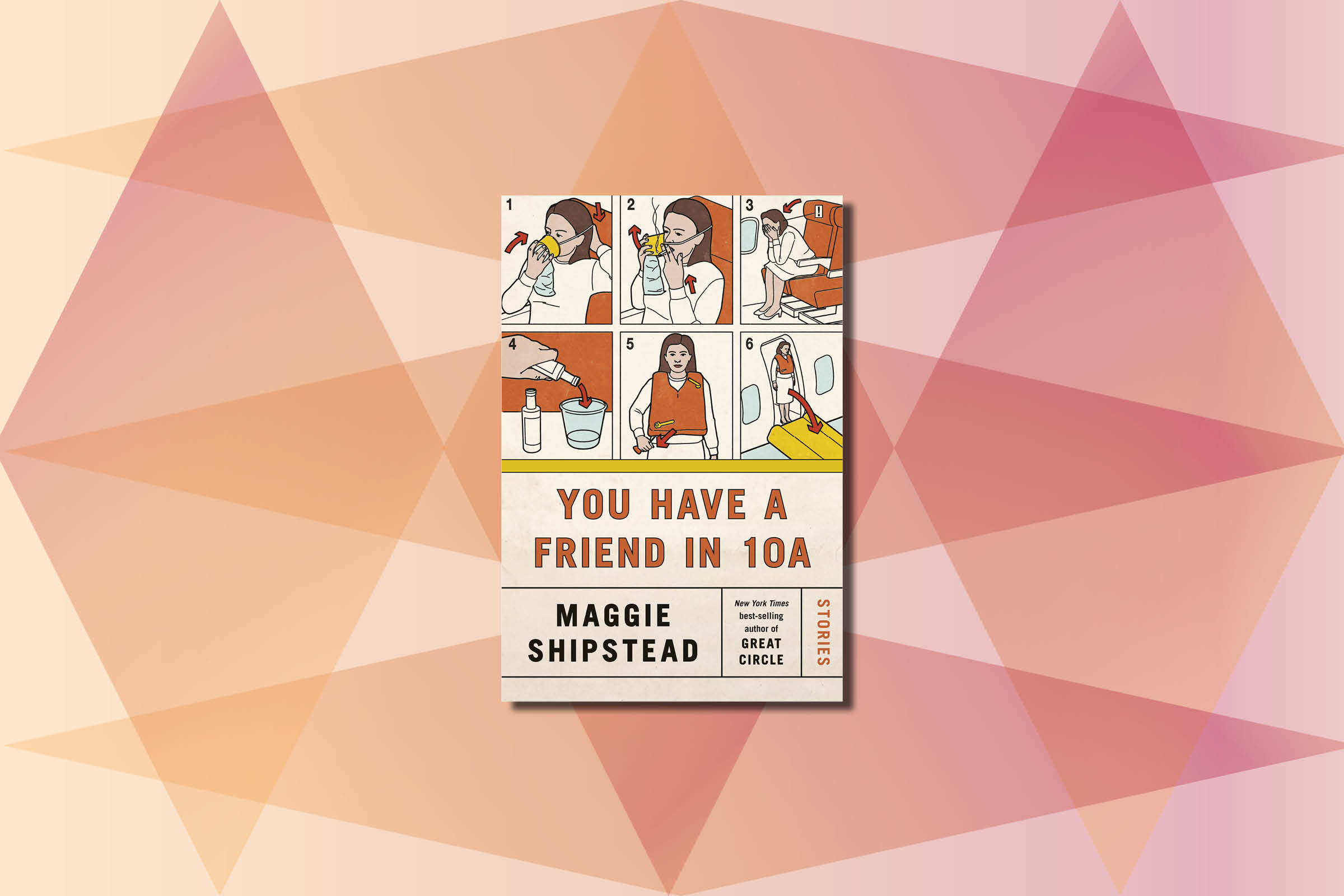

Last May, Maggie Shipstead released Great Circle, a sweeping, 600-page epic that flips between the lives of a 20th-century pilot who goes missing and a present-day actor playing the pilot in a major biopic. One year later, Shipstead returns with more reflections on Hollywood, fame, and travel—this time in the form of a short story collection, You Have a Friend in 10A.

Long before she wrote Great Circle—which shot Shipstead to the top of the literary world as it became a best-selling Booker Prize finalist, set to be adapted for television—she was working on short fiction and dreaming of being published in a literary review. As a student at the prestigious Iowa Writers’ Workshop, the author began writing what would become the first piece in her debut collection. The book, coming May 17, includes 10 stories, all published between 2009 and 2017 in literary journals and sites.

The stories vary in subject, from a love triangle in Montana, to a complicated relationship between a gymnast and a hurdler at the Olympics, to the titular story about a former child actor on an airplane who has recently broken away from a cult. Like Great Circle, the collection probes the complexities that surround celebrity and ambition—and they contain a transportive quality, reminiscent of Great Circle, as they take readers across continents and decades.

Shipstead, who has spent the past eight years exploring the world on assignments for her work as a travel journalist, spoke to TIME from Los Angeles about revisiting her early writing, why she likes creating celebrity characters, and the surprise success of her last novel.

Read More: Here Are the 14 New Books You Should Read in May

TIME: The stories in this collection were written over more than a decade. What was it like revisiting them?

It’s always helpful when time defamiliarizes you from your own work. The short story taught me how to be a writer—it was the most efficient way to get better. Looking back at them, I can see what I was experimenting with and the little breakthroughs in each one.

You feature several characters that are either famous or adjacent to fame. What draws you to that experience?

Celebrity gossip is our substitution for when we lived in smaller communities—we knew more people in common and had gossip we could all take part in. Writing about Hollywood tropes or riffing on existing stories allows you to start with a pre-established familiarity for the reader. Fame is so fascinating: there’s so much glamour, there’s artifice, there’s underlying skeeviness. Sometimes there’s just a mundane aspect to it. I can’t resist it.

Are you a tabloid reader?

Less and less, because it’s so fragmented now. When I was a teenager, and later, everyone picked up People magazine at the grocery store or the doctor’s office, and you knew who everyone was. Now I’m like, Who are these people? The online influencers and HGTV stars, I have no idea who they are.

What do you make of the success of Great Circle?

It was a nightmare to write. I wasn’t on contract for it, and it took years and years. The success has been gratifying. The book tapped into certain appetites, and the fact that it was published during COVID actually changed its significance. This is a book about someone who feels it is essential to have freedom of movement, and it came out right in this moment when that was what we didn’t have. There’s a fashion right now for books that are fragmented or autofictional. I like those books, but there’s always room for a more epic story.

There’s been a surge of pandemic-related fiction. Do you gravitate toward that subgenre?

It’s going to be a huge quandary going forward. The book I’m starting right now, I’m trying to set very recently—so you inevitably bump up against the pandemic. There will be a lot of fiction that goes through this time period but isn’t about the pandemic in the way some of the earlier stuff was. We’re still living it, so I don’t have a huge hunger to think about it more than I already do.

You sold the television rights for Great Circle last year. Would you ever write for TV?

A lot of novelists think, Oh, how hard can it be? But writing for television is a really different skill, and you give up so much of what’s in your toolbox in order to do it. Maybe someday.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Annabel Gutterman at annabel.gutterman@time.com