The lockdown in Shanghai is now in its sixth week and residents have been flooding social media with disgruntled posts. Some document their confinement in quarantine centers without beds or blankets. One pensioner says she is unable to receive the heart medicine she needs. A woman gripes that her family refuses to eat the meager cabbage soup she has improvised for them from her dwindling larder. Many parents have been forcibly separated from their children and videos of unaccompanied infants crying in a Shanghai COVID-19 hospital have gone viral.

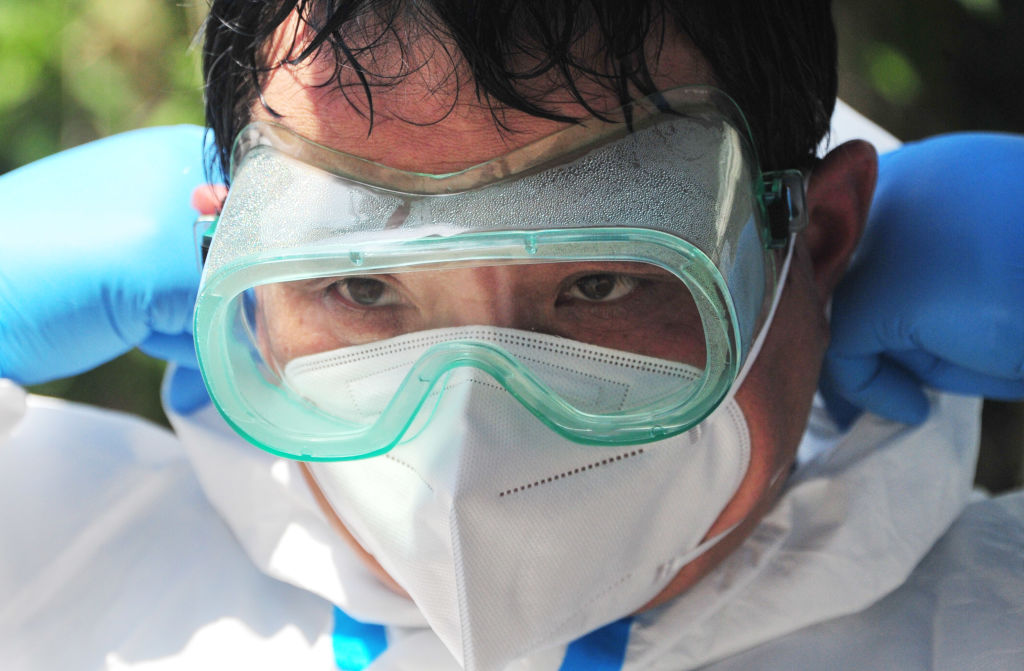

Across China’s most populous city, mental health has taken a severe battering. But just as residents thought they were through the worst, restrictions were tightened once again this week. Now, if somebody tests positive, all the residents of their apartment block, and not just close contacts as before, will be isolated in quarantine centers. Food deliveries are banned in at least four of the city’s sixteen districts. Videos have been shared of sanitation workers—dubbed dabai or “big whites” on account of the PPE they wear—entering homes without permission and spraying disinfectant. (The resulting outcry led to a pledge from city authorities to end the practice.)

The new measures come in spite of ten consecutive days of falling cases and just 322 locally transmitted COVID cases on May 8. There were 3,625 local asymptomatic infections and 11 deaths reported the same day—for a city of 26 million.

Read More: The Chinese Public Is Divided Over Zero-COVID

Despite growing unease about lockdown measures, President Xi Jinping doubled down on China’s zero-COVID strategy during a May 5 meeting of the Politburo Standing Committee, the nation’s top political body. The stakes are high. Allowing COVID-19 to spread in China would lead to a “tsunami” of cases, according to a new study by Shanghai’s Fudan University, Indiana University, and the U.S. National Institutes of Health, published on May 10 in the peer-reviewed Nature Medicine. Researchers estimate that China would be hit with 112 million cases in a three-month period, leading to 1.5 million deaths. “We project that the Chinese healthcare system will be overwhelmed with a considerable shortage of ICUs,” they said.

But the strategy is pushing many Chinese to breaking point. Videos of their hardships are posted and shared by millions, just as quickly as censors scrub them from the Internet. Unusually, there have even been protests, with people in some neighborhoods of Shanghai gathering on their balconies at prearranged times to bang pots and pans in frustration. Some have been arrested.

On expatriate resident, who asked to remain anonymous for fear of harassment, spoke to TIME of the city’s anger. “I don’t think it will lead to an uprising or anything like that,” he says. But in his view “the government has definitely lost credibility in the eyes of people here.”

China’s zero-COVID dilemma

While much of the world is opening up and attempting to live with COVID-19, China exists in a sort of parallel universe. Major cities can be swiftly locked down for a handful of cases. People can spend weeks living in their offices, unable to go home. Health apps on every mobile phone govern freedom of movement and whether or not a person can use public transport or enter public facilities.

If there is little or no indication when this zero-COVID strategy will change, it is because it has been a great success. Despite the fact that the virus first emerged in the central Chinese city of Wuhan in late 2019, the world’s most populous country has officially recorded 1.1 million cases and 5,191 deaths for the entire pandemic. While some dispute these numbers, there is no doubt that China’s toll is a small fraction of the 998,048 American lives lost to date.

But China’s approach has created problems of its own. In recent weeks, Premier Li Keqiang has issued several warnings about the economic impact, while unemployment across a sample of 31 major Chinese cities is now the highest on record. Meanwhile, the low COVID death rate has lulled some Chinese, particularly the elderly, into a false sense of security.

Read More: COVID Separates Parents From Children in Shanghai

More than 1.24 billion of China’s 1.402 billion people have been fully vaccinated, according to official figures, but tens of millions of seniors are either unvaccinated or partially vaccinated, and thus at high risk of falling seriously ill if they catch COVID. The tragic example of Hong Kong, which has one of the highest coronavirus deaths-to-population ratios in the world, shows what can happen when the elderly are not sufficiently protected from rampant Omicron.

The country is now in a catch-22. “Zero-COVID became self-justifiable,” says Dr. Yanzhong Huang, senior fellow for global health at the New York City–based Council on Foreign Relations. “The more success they had increased the immunity gap between China and the rest of the world, which made it even more justifiable.”

Zero-COVID also relies on continuous testing, and isolation of positive cases, on a massive scale. Some experts question such use of resources. Shanghai has mobilized 100,000 health professionals—half the city’s medical workers—just to conduct PCR testing and on April 4 managed to test all 26 million residents in a single day. It was an undeniably impressive feat of logistics, but “It would probably be more cost-effective to double down efforts to vaccinate the elderly population, rather than pursuing all these mass testing, quarantine and lockdown measures,” says Huang.

Political factors behind China’s zero-COVID policy

Adding to the problems are the politics of zero-COVID, which has by now become of President Xi’s signature policies. China’s strongest leader since Mao Zedong is seeking an unprecedented third term at the five-yearly Chinese Communist Party Congress in the fall. Any questioning of the policy’s effectiveness will be seen as a direct affront to his authority. “We will resolutely struggle against all words and deeds that distort, doubt, and deny our epidemic prevention policies,” Xi recently declared.

While much of the world is opening up and attempting to live with COVID-19, China exists in a sort of parallel universe

In March, a Standing Committee meeting called for “balancing” pandemic control and economic development. But such talk was conspicuously absent at the recent meeting of the Politburo Standing Committee. These days, cargo ships are backed up at ports, warehouses sealed, factories mothballed, and trucks unable to unload goods.

Investors pulled a record $17.5 billion in stocks and bonds out of China’s market in March as analysts warned no end to disruption was in sight. Telsa was forced to abandon a plan to reopen its Shanghai megafactory on April 4 due to supply issues. Foreign workers are fleeing the city in droves. None of this appears to have shaken the leadership’s resolve.

It has, however, left many ordinary people in shock and many officials unable to explain the policy. In one widely-shared video, a group of dabai order some reluctant Shanghai residents to vacate their apartment after a neighbor tests positive.

“You can’t do whatever you want—unless you’re in America. This is China,” one dabai says, clutching a spray bottle of disinfectant. “Stop asking me why, there is no why. We have to obey national guidelines.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Write to Charlie Campbell at charlie.campbell@time.com