Fifty years ago this June, Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 was signed into law. It states that “No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.” While often associated with sports, Title IX guarantees gender equality well beyond sports, covering all aspects of educational programs including access, scholarships, the treatment of individuals and employment. In addition to opening opportunities to girls and women, Title IX posits that the terms of those opportunities should be free from sex discrimination. In example, it requires schools to prevent and remedy sexual harassment and sexual assault and prohibits discrimination against pregnant and parenting students. It is, arguably, the most important law for women and girls since women were granted the right to vote in 1920.

Congresswoman Patsy Takemoto Mink, a four-term Member of Congress from Hawaii in 1972, played a pivotal role in developing and defending Title IX. Her work, along with that of collaborators in Congress and allies in the women’s rights community, changed the course of history and enabled generations of girls and women to pursue their interests, goals and dreams. The rise of girls’ and women’s athletics, the movement of women into professions like law and medicine, and the empowerment of women seeking justice against sexual violence and harassment — these and other steps toward gender equality depend on Title IX.

One of the first feminist legislators, Mink brought her own lived experience to the halls of Congress while also giving voice to the equality needs of girls and women based on their collective experiences. Mink recognized and understood the importance of breaking down barriers before the concept of gender equity was fashionable, or even acknowledged. Moreover, she wanted to break down barriers for everyone, transforming individual women who managed to break through existing barriers from anomalies to trailblazers for other women.

Sex discrimination had altered Mink’s path in life, its stubborn norms and rules affecting millions of women to similar effect. Mink had aspired to become a physician from the time she was four years old. She was unable to realize that dream when all the medical schools she applied to denied her admission, some explicitly stating they did so because she was female. At the time, only around 4% of medical school students were women. Mink changed course and applied to law school. Although law schools were also male domains, Mink eventually became one of two women, and two Asian Americans, to graduate from the University of Chicago Law School in 1951.

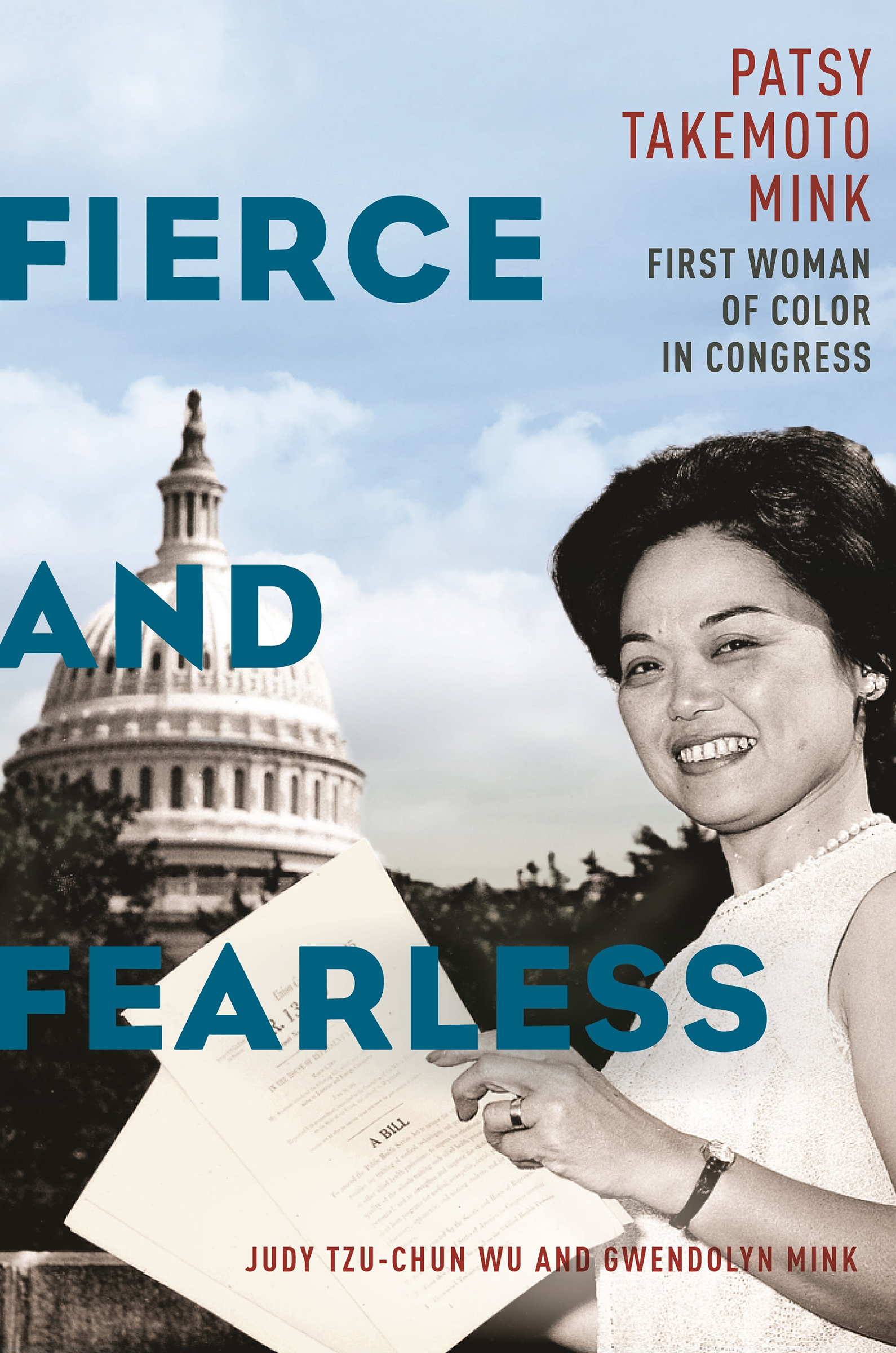

Despite these credentials, she could not find a job in a traditional law firm—many pointed to the fact that she was a mother and, therefore, assumed she couldn’t handle long hours; others did not like the fact that she was married, presuming her first loyalty and obedience to be to her husband. Frustrated but undeterred, Mink set up a solo practice. She also became active in the territorial Democratic party of Hawaii, which developed new strength and purpose in the 1950s. Although few women served in elective office, Mink ran and won election to the territorial, then state, legislature. In 1964, she became the first woman from Hawaii, the first Asian American woman, and the first woman of color elected to Congress. She went on to serve twelve terms in office, from 1965 to 1977, and then again from 1990 to 2002.

Mink’s road of “firsts” was paved in Hawaii. A third generation Japanese American, Mink was born on the island of Maui and grew up in a stratified plantation society.

Her family’s Maui beginnings shaped Mink’s worldview and subsequent career. Her grandparents were subject to racialized naturalization laws that designated them forever foreigners, “aliens ineligible for citizenship.” Not until 1952 did Japanese and other Asian immigrants gain naturalization rights to become US citizens. Although Mink was herself a U.S. citizen by birth, the racist exclusion of her grandparents from equal participation in the U.S. community was a stain and a lesson that weighed heavily.

Read more: My Mother Was One of the First Women to Run for President

Entering Congress for the first time in 1965, Mink’s very presence signaled resistance to the gendered nature of political culture, while her convictions brought new issues and perspectives to the policy table. In local politics during the 1950s, Mink had worked to halt nuclear testing, protect labor rights, and advance gender equity through equal-pay-for-equal-work. She carried these commitments into Congress, while advocating additional goals, such as universal child care, transparency in government, environmental protection, educational opportunities, and ending the war in Vietnam.

Although Mink often was the only woman in the room or on the dais, she did not work alone. In general, but especially regarding feminist policy, Mink served as a political “bridge,” working in tandem with grassroots advocates to effect legislative change. Rachel Pierce coined the phrase “Capitol Hill feminism” to describe how “women on the Hill adopted and adapted the rhetoric, ideological precepts, and policy goals of the women’s movement.” Professor Anastasia Curwood uses the term “bridge feminism” to describe how Mink’s colleague, Congresswoman Shirley Chisholm, connected the African American civil rights and women’s movements with the grassroots and legislative arenas. By partnering with allies in and outside of Congress, Mink amplified the voices of those not traditionally welcome in policy venues. This approach created the ideal environment for the pursuit of Title IX.

The brainchild of both Mink and Oregon Congresswoman Edith Green, Title IX encapsulated their commitment to end sex-based discrimination in education. Each had worked for several years on legislative vehicles to achieve equal opportunity for women in education. For example, a comprehensive ban on sex/gender discrimination in federally funded programs, including education, was spelled out in Mink’s Women’s Equality bill, which she introduced in the spring of 1970. This bill, as well as Edith Green’s legislative initiatives, took Title VI of the Civil Rights Act as the model. Title VI had barred race-based discrimination in programs that receive federal funds. In the end, the concept of gender equality in education, couched in the same language as the Civil Rights Act, was wrapped within Congresswoman Green’s omnibus education bill, as a provision eventually known as Title IX.

While Title IX represented an incredible liberal feminist achievement, it was also very personal. Title IX supporters were motivated to demand these reforms in part because of their own experiences of educational exclusion. The radical feminist mantra that “the personal is political” resonated with Title IX advocates who knew well how gender bias in school had circumscribed their own opportunities. Mink’s own educational experiences as a woman of color and a mother contributed to her own identity as a civil rights advocate for women.

Read more: 100 Women of the Year

For Mink and other feminist advocates, Title IX was a milestone for gender equity. But as Mink remarked in celebrating the 30th anniversary of Title IX in 2002, Title IX is only as significant as it is effective, and its effectiveness requires us all to be ever-vigilant about enforcement. After her death in 2002, the official name of Title IX was changed in her honor to the Patsy T. Mink Equal Opportunity in Education Act. This fitting tribute foregrounds the pivotal contributions of a woman of color, an Asian American, and a representative from Hawaii in achieving the government’s pledge to promote women’s equality in education. Fifty years on, it is now our turn to make sure that the goals of Title IX are guaranteed to generations that follow us.

Judy Tzu-Chun Wu is a Professor of Asian American Studies at the University of California, Irvine and serves on the National Women’s History Museum’s (NWHM) Scholars Advisory Council. Gwendolyn Mink is a political scientist and independent scholar. Their co-authored book, Fierce and Fearless: Patsy Takemoto Mink, First Woman of Color in Congress, was released on May 3, 2022.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com