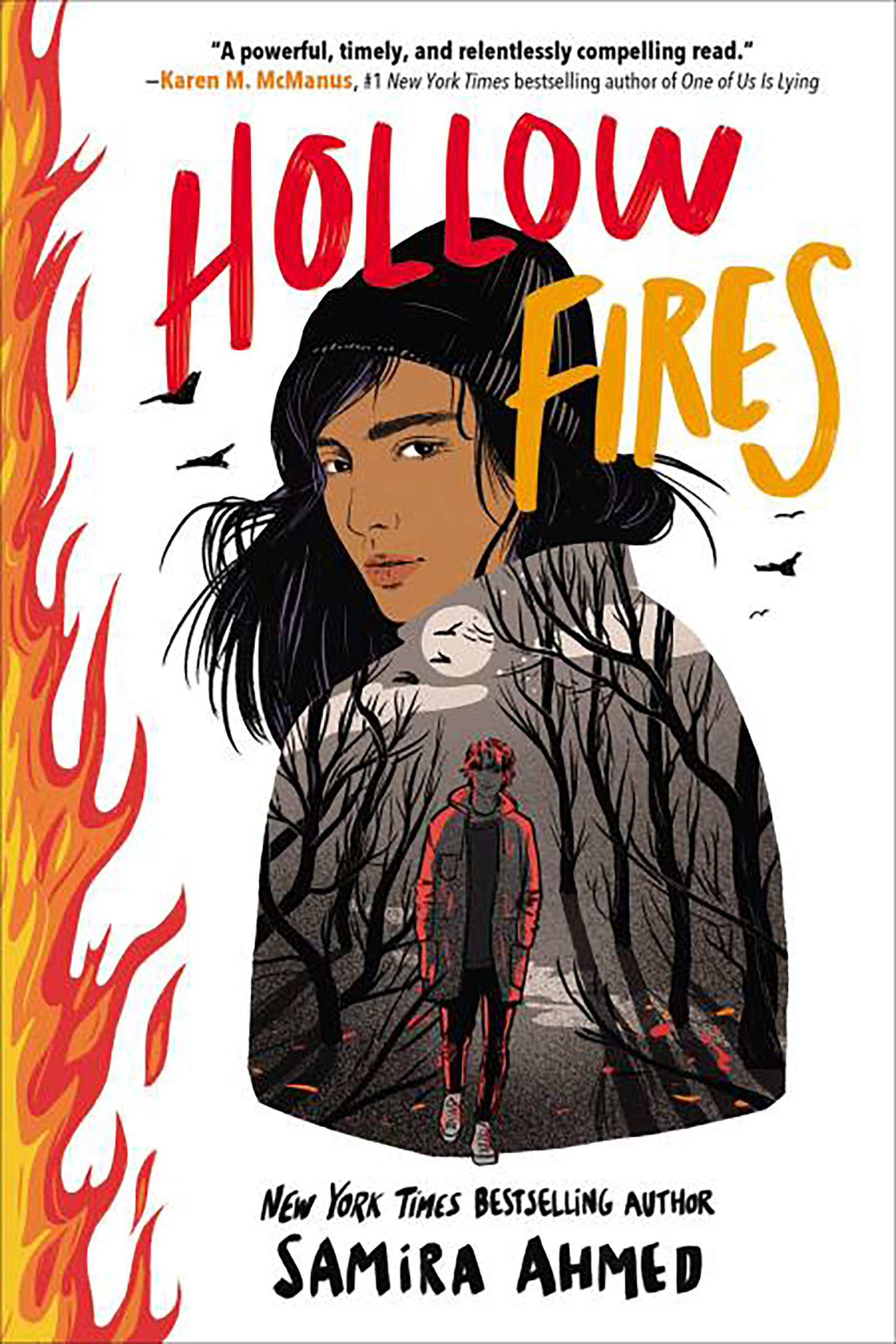

As editor of her high school newspaper in Batavia, Ill.—a small town about an hour west of Chicago—Samira Ahmed got used to asking tough questions. The paper was where she first thought deeply about flawed notions of objectivity. And it’s part of what influenced the dogged nature of the protagonist of her new young-adult novel, Hollow Fires, set to publish on May 10.

Hollow Fires follows 17-year-old Indian American Safiya Mirza, a student journalist in Chicago, as she embarks on a mission to find out who killed 14-year-old Jawad Ali, a local boy who went to a public school in the city.

Jawad, the son of Iraqi refugees, had a passion for science. Less than three months before his death, he brought a homemade jet pack to class—only to be reported to the police by a teacher for wearing “something like a suicide bomber vest.” The arrest was traumatic, and after his death, it stains his legacy, lending him the nickname “bomb boy.”

In Ahmed’s novel, Jawad remains an active character, a ghost who struggles to communicate with Safiya as she investigates his death. “All I am is a whisper in the dark to a girl who doesn’t want to believe in ghosts,” he says. “How do I get Safiya to believe in me?” All while trying to uncover the truth about what happened to Jawad, Safiya must navigate white supremacy, a nerve-wracking crush, and some cryptic and frightening clues.

Ahmed, 51, is also the author of Internment, and the first South Asian woman to write the comic book series Ms. Marvel. She spoke with TIME about the events that shaped Hollow Fires, how media and police bias impact the response to crimes, and her thoughts on the upcoming Disney+ TV series Ms. Marvel.

Could you tell me about the process of writing Hollow Fires? What was most challenging?

One of the hardest things was tying all the novel’s elements together. Hollow Fires is a story about a murder told from the viewpoint of Safiya. But it’s also the story of Jawad. And there’s a found-document element—snippets from social media, news reports, and blog posts. I wanted to ask questions about the way media speaks about murder and hate crimes, particularly in relation to race, ethnicity, and religion. Often, the media is unwilling to self-examine.

At one point in the novel, Safiya shares how she hated how everyone forgot Jawad’s name and instead referred to him generically as an Arab American teen or son of Iraqi refugees. What were you trying to say here about identity?

I wanted to examine how race is involved in the way that the press, police, and people on social media treat the victims and perpetrators of crime. Hollow Fires is set in Chicago—a diverse city with huge immigrant populations. If you look at the the clearance rate for police solving murders in the city, WBEZ found that it’s much higher if you’re white. In 2019, the clearance rate for murders in Chicago if the victim was white was 47%; if the victim was Hispanic it was 33%, and if the victim was Black, it was only about 20%. It made me think about which victims are advocated for, and in my research I found so much erasure of people of color, Black trans women, and Indigenous women in particular. All of that was swirling around in my mind.

What real-life news events shaped the narrative? The story of 14-year-old Ahmed Mohamed in Texas comes to mind. Police arrested him for possessing a homemade clock that his school said looked suspicious. Was there an intentional link there?

His story is definitely one that stuck with me, although it’s not an isolated incident. There are so many stories about the young Black boy or brown girl or Muslim kid being viewed as suspicious.

With Ahmed, you have this young boy who is bringing in this clock that he’s disassembled and reassembled in this cool way. He’s so excited to have reverse-engineered something and just wants to show his teachers. As a former teacher, I can just imagine this curious, inventive kid coming to school and then having a teacher be immediately suspicious and call the police on him. It was a heart-wrenching incident. Right-wing media jumped in with conspiracy theories saying he may actually have terrorist links. The family received threats. They left the country.

A lot of my young-adult fiction speaks to issues like this: moments in life, when childhood is shattered. Too often, adults put young people in terrible positions—choices that adults make impinge on young people’s lives in ways that they’re not prepared for and that are so deeply unfair.

What personal experiences informed how you told the story?

People think Islamophobia in America began with 9/11. But it actually has much deeper roots. I was 7 or 8 and living in Chicago during the Iran Hostage crisis in 1979. Two white men pointed at me and said, “Go home, you goddamn f—ing Iranian.” It was very violent language, especially for adults to use against a child. I was confused for a second, like, What do you mean, go home? Do they know that I don’t live in Chicago and that I live in the suburbs? I remember thinking, Why do they think I’m Iranian? I look so Indian. Later, I realized: they’re racist, and racists are bad at geography. They think we’re all from the same place.

I have had so many other experiences since then. My last name is Ahmed. And in the olden days when we had phone books, whenever there was any kind of incident in which a Muslim was suspected, I would get calls all night long saying, “Go home, f—ing terrorist” and “Go back to your own country.”

My experience with Islamophobia and racism has always had this theme of “go home.” And pieces of that come up in almost all of my novels. Virtually every person who’s an immigrant or a child of immigrants can understand this experience. And we are seeing it a lot with this rise in anti-Asian hate during the pandemic. I just want to be clear with young people that no one is allowed to tell you to go home when you are home.

How did you handle balancing the heavier aspects of the novel—the murder of a young boy—with the levity and lightheartedness of teenagers on a mission?

I want to honor young peoples’ stories and to write them as they are. That means you can be in the midst of something horrifying and devastating, but you’re also a teen, and maybe you have a crush on someone, or you’re dealing with the fact that you really don’t want to write this paper, or your parents have put this curfew on you. I don’t think I can write a book that’s about deep sorrow and nothing else. I try to put hope on every page, even when it’s dealing with dark subjects.

You’ve been involved in writing comics for the Ms. Marvel series. Are you also involved in the upcoming TV show?

No, the TV show is separate. It’s really cute because kids in my neighborhood know that I write Ms. Marvel comics, and they’ve been asking me if they can get parts on the show. I tell them I wish I could. One time, a kid came up to me and said, “You’re writing Ms. Marvel, right? You better not mess it up.”

With great power comes great responsibility, right?

Yeah, exactly. I said I’ll do my best, but I love their passion for this character. And I love her, so I’m going to try and do right by her.

How do you feel about the upcoming Disney+ series?

I’m excited about it. Every child should be able to see themselves as a hero on the page and on the screen. And Ms. Marvel gives that opportunity for so many young people to see themselves in a way they’ve never gotten to before. Especially for young Muslim kids and young brown kids in this country: we’re so often portrayed as terrorists. When you’re always the bad guy, it’s very traumatizing for kids.

Any other parting thoughts you would like to share?

The whole time I was writing Hollow Fires, I felt like the U.S. is at this inflection. We’re facing this crisis of philosophy in terms of who we are as a people. One of my novels, Love Hate & Other Filters, has been restricted by Madison County, Mo. schools; the school board vote deciding whether to ban it is on May 9. This entire anti-critical race theory movement is about denying our history and erasing entire identities. It’s so important to speak out against this. America likes to bury the truth about itself. Part of what my characters do in these situations is to uncover the truth, even when it’s difficult, and face it.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Sanya Mansoor at sanya.mansoor@time.com