On Feb. 18, 1868, in Charleston, S.C., Radical Republican Solomon George Washington Dill, known as S.G.W. Dill, rose at South Carolina’s Second Constitutional Convention to offer a resolution that would protect sharecroppers and tenant farmers, including formerly enslaved Black people, from gouging by white landowners. The resolution was tabled but when Dill, a white man, was allowed to speak, he said, “I insist on giving the poor man justice and all that truly belongs to him . . . Numbers of them are oppressed; numbers are without homes, without shelter, and cannot obtain it unless they give more than one-half of their physical labor to their landlords for shelter … I am begged to do something for them towards keeping the landlords in check.”

In taking this strong stand, Dill put his life at risk. Elected to represent Kershaw County he never got to serve his full term in Columbia. On the night of June 4, 1868, Dill was assassinated by assailants who were never found, though many reported the men belonged to the Ku Klux Klan. Dill’s killing fit the pattern of Klan violence against whites who acted in the interests of the poor against the interests of wealthy landowners.

During Reconstruction, the Klan acted as the paramilitary arm of the Southern Democratic Party and of white landowners. The Klan’s goal was simple: keep the poor, Black and white, from encroaching on the economic power of the wealthy. Ultimately, the Klan and their wealthy white backers were victorious but not before the formerly enslaved, and their supporters, scored several major victories that were then ripped away through white violence.

Read more: Reconstruction Didn’t Fail. It Was Overthrown

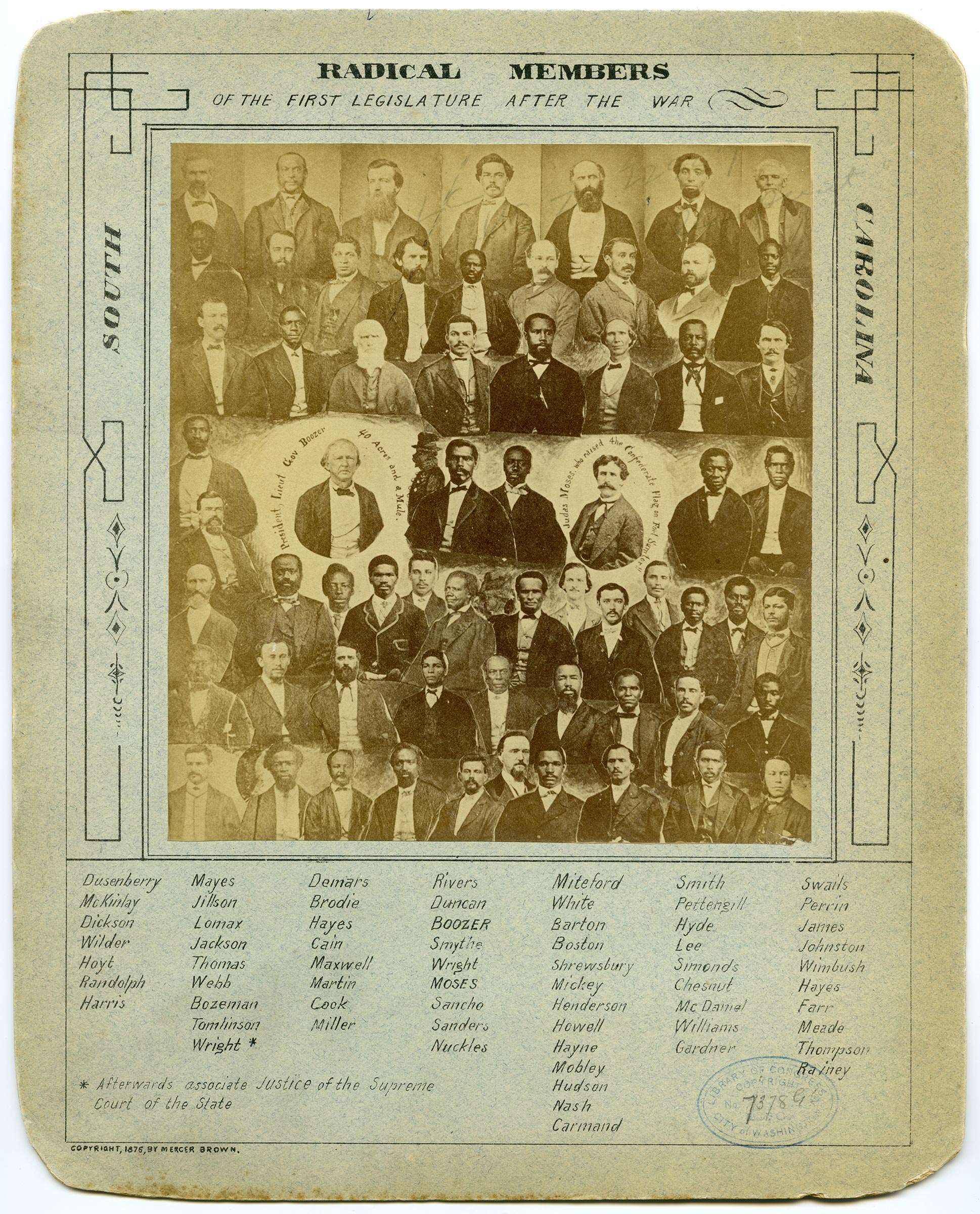

During the Reconstruction period—from 1865 to 1877—thousands of formerly enslaved people across the South were voted into office. They controlled politics from local police departments to state legislatures, and in some instances the governor’s mansion itself. State legislatures passed tenancy laws to protect sharecroppers and tenant farmers; passed bills making it easier for poor people to obtain credit; and created state agencies charged with looking out for the poor. Reconstruction justices and juries, many of them Black, delivered verdicts in favor of poor farmers, Black and white, against wealthy landowners. Across the south, Black men, such as Blanche K. Bruce, a U.S. senator from Mississippi, and James T. Rapier, a U.S. representative from Alabama, owned and operated large plantations of a thousand acres or more.

At the same time, state legislatures had been charged by newly approved state constitutions to meet more of the public need in education and care of the poor, in hospitals and mental health facilities. A new tax structure followed this new set of public priorities. Combined with huge state deficits incurred during the Civil War and a collapse in the credit market for the South, southern states moved aggressively to raise property taxes, in some cases by a factor of 10, when compared to the pre-war period. Black-run legislatures believed this might be a market-driven solution for land redistribution. Owners of large plantations and huge tracts of land would either be forced to sell or have their land confiscated for failure to pay taxes. That land could then be redistributed to landless formerly enslaved and to poor white people.

While land redistribution by taxation rarely happened, the period saw the country embarking on a road toward wide-scale democracy and racial justice. But the period ultimately descended into violence as white Americans allowed their fear of the power of the formerly enslaved to trump their embrace of equality and fairness.

Increased taxation sent plantation owners up in arms, and gave them a way to shift the focus of their attack from race to taxes, even though race was very much beneath the taxation issue. Such anger on the part of wealthy whites contributed to the rise of violent groups supported by them, such as the KKK, and ultimately to an organized, successful political effort to undo Reconstruction through violence.

The era of Jim Crow began. Lynchings became commonplace entertainment for whites. Voting rights came under attack as Black voters were forced at gunpoint to vote for racist white Democrats. Armed gangs patrolled polling stations to prevent Blacks from voting. Groups like the White League and the Red Shirts joined with the Klan. On Dec. 12, 1874, the white president of the board of supervisors in Vicksburg, Mississippi, received a telegram from white mercenaries in Trinity, Texas offering their services to “kill out your negroes.” Northern newspapers also stepped into the fray, whipping up fears of “Africanization,” the code word used to describe the wide-spread, successful exercise of political power by the formerly enslaved.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

White violence sought to turn back the tide of Black progress. Or, as the motto of Horatio Seymour and Francis Blair—the 1868 Democratic candidates for president and vice president put it on their campaign badges, “This is a white man’s country: Let white men rule.”

White hatred and white violence was directed against Black men, like those running the Second Constitution Convention in 1868 in South Carolina. Meeting in Charleston, they passed sweeping reforms in voting rights, civil rights, greater diversity in politics, wealth redistribution, taxation reform, prison reform, universal free education, women’s rights, care for the indigent, expansion of credit, and social safety nets. One would not be faulted for believing these the accomplishments of a progressive movement of the 21st century, rather than the efforts of the formerly enslaved, and their supporters, in the 19th century.

Reconstruction was a unique moment. For the first time ever in America, Black people were allowed a share of, and a say in, the institutions of American power and wealth they helped to create. And, to the dismay and chagrin of many white Americans, even though Black Americans had endured 250 years of slavery, they showed they were fit for the task. Reconstruction was not perfect. Hidden within its broad accomplishments were also the seeds of its eventual, violent demise. But for a decade, at least, from the late 1860s to the late 1870s, America tentatively trod the road toward true democracy.

Adapted from Of Blood and Sweat: Black Lives and the Making of White Power and Wealth by Clyde W. Ford, available now from Amistad, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.Copyright © 2022 by Clyde W. Ford.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com